| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Women Art Revolution

I'm already on record here at DVDTalk as trying and failing to like the multimedia artist Lynn Hershman Leeson's own personal work as a filmmaker, so I was half-intrigued, half-wary as I prepared to sit down with her documentary about the omitted history of women artists in the latter half of the 20th century, !Women Art Revolution. Happily, my leeriness wasn't entirely warranted, as the subject at least diverts Leeson from the self-involved, pseudointellectual insularity I find to run rampant through her narrative/avant-garde video works. For this film, Leeson has skimmed some of the most salient pieces of a career-long project in which she has aimed to preserve a history that has, as she points out, too often been marginalized: the history of both women/feminist artists and the activists who have worked hard over the decades to point out and fight back against the very real, institutionalized discrimination those artists faced. But as usual when it comes to the subject of art by any minority or marginalized group, some very sticky, cloudy issues of representation, how to measure the quality of an artist's work, and how to go about increasing inclusiveness (as well as the especially scary, unanswerable one, how does one define "art" in the first place?), all present themselves as inevitable obstacles, and the question becomes, will Leeson have the insight, perspective, and inquisitiveness to give us a history that will face those tougher issues and give us not just a mindless, mutual-appreciation-society celebration but something to engage with and learn from?

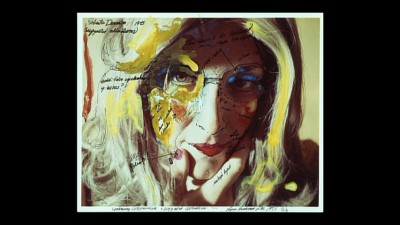

!Women Art Revolution does excavate a sort of parallel history that is given short shrift in most official accounts of art movements and phases over the artistically very hectic, doubt-ridden second half of the 20th century. That word "official" is key: As Leeson presents it, repercussions from the civil rights movement of the 1960s represented, in the art world, a splitting-off from the more and more minimalist, ostensibly apolitical art being made, curated, shown, and written about mostly by (white) men in the 1960s and 1970s, and her subjects are women who made art in those days and had to find (and, often enough, create) channels far outside the official ones in order to find ways of creating their work, displaying it, and generally being considered "real" artists. To this end, Leeson has gathered together interview footage of women artists taken in recent years with stuff she shot decades ago (sometimes of the same, evolving women), and she includes these alongside a generous peppering of clips from their work. Among them are graphical/painting/collage artists like Nancy Spero or Howardena Pindell, installation creators such as Judy Chicago, the choreographer-turned-filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, and performance/video artists like Martha Rosler and Miranda July (with all the film's interview montages and graphic manipulations set to a punkish soundtrack by the best-known riot grrrl in the world, Sleater-Kinney guitarist/Portlandia star Carrie Brownstein).

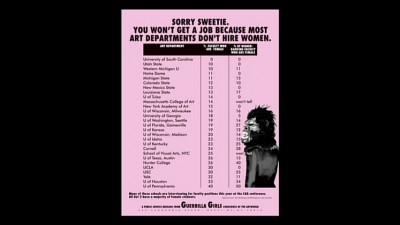

Leeson also casts her net far enough outside the art world to encompass interviews/commentary with critic B. Ruby Rich, who lived through and directly experienced the various breakthroughs and upheavals in this secret feminist history of modern arm, as well as discussion with different members of The Guerrilla Girls (a prankish, gorilla mask-wearing activist group dedicated to gathering provable facts and statistics, and naming names, to expose sexism in the art world). This approach makes for a nice sort of thumbnail for the project of which the film itself, we are reminded fairly consistently throughout, is really just the iceberg-tip: a huge online archive that includes every moment of Leeson's years of interviews conducted for the film (which can be accessed at the Stanford library website) on top of the website RAW/WAR, a place for aspiring artists to upload their work, confer, network, and generally keep on working outside the jurisdiction of those self-appointed "official" arbiters of art.

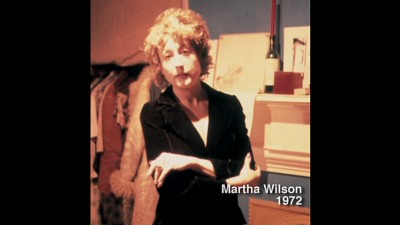

The film's saving grace (what rescues it from succumbing to Leeson's Oprah-like, quasi-mystical, wannabe-profound voice-over narrations, always delivered in her pedantically intoning, female-Michael-Moore voice that I happen to find personally insulting, since I don't care to be spoken to like I'm a very slow child) is that multitude of other voices. When Leeson gets off of herself and stops interjecting her thoughts (almost all of which sound like she just took first-year theory and is parlaying that into confessional poetry), the film is rife with an actually refreshing, diverse representation of a movement (feminism) whose ideological litmus tests and internecine battles all too often meant that its most hopeful, radical, and envelope-pushing bids for liberation, like so many other idealistic experiments, were prone to sabotaging themselves from the inside out, when it already had plenty of exterior opposition. So Leeson goes out of her way not to give us only one experience or one woman's version of this forgotten history: For every inflexible, conversation-hogging Judy Chicago (admittedly also a talented artist and tireless activist for women in art whose installation work The Dinner Party was the subject of a 1990 congressional debate on public funding for the arts, of which Leeson doesn't neglect to give us glimpses, and which is probably the most disturbing thing in the film, since it shows our elected officials to be belligerently philistine), there's a Martha Wilson, who here relates, in a 2006 interview with Leeson, how in 1972 she entered Chicago's newly-founded women's-art domain at Cal Arts and was promptly chewed out when she opined that the flowers and breasts she saw everywhere in the work there were "prescriptive." And good for Wilson that she didn't follow that prescription, despite being intimidated by a self-appointed gatekeeper of what feminism and feminist art is: her starkly imaginative, identity-exploring photographic work is very accomplished, at least as good as Chicago's, and has perhaps a bit more bite because it's more disturbing and doesn't feel the need to be "affirmative."

And there's the rub. How does one nurture, support, and "affirm" while at the same time providing the sort of rigor, the kinds of definitions of what specifically makes this video or that painting effective? From whence will come the limits, the standards, the risk of failure that every artist needs if they are to push themselves further and harder to make great work? One of the most difficult things faced by both the spectator and the artist when discussing art by women is the censuring, even bullying way in which some feminist practice has refused us the idea that any work can be superior to any other work (to prefer a great artwork by a man to a less well-realized one by a woman is sexist; to prefer one woman's work to that of another is divisive, sabotage), leaving one with the dismal choice of being sexist or a sellout for opining that a work of art by a woman is badly made, dull, or ineffective, even on its own terms; or, on the other hand, being an uncritical zombie, admiring a work of art and any institution that shows it, regardless of its artistic success or failure, simply because it's important that women artists be given a fair chance. But there is a bigger picture that that unpleasantness plays out in, one in which that seemingly unavoidable, paralyzing hypersensitivity--the perpetually loaded question of how the lack of acceptance for a work by the lone woman (or black, or gay) artist when faced with criticism of their work, however valid, means undermining of the fragile aspirations of all female (or black, or gay) artists--could be ameliorated if the field of minority artists was wider, their opportunities greater and more varied. This fundamental part of the problem, too, is something usefully raised in !Women Art Revolution, which allows it to explore a bigger picture than the occasional pettiness and paranoia that perhaps inevitably arise when these touchy matters are discussed.

By a similar token, there is an "equality"-seeking way of thinking that says everything overlooked must be brought back out and examined, simply because it was overlooked. As Leeson shows here, there is some validity to that: something like Martha Rosler's video piece Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained, or the work of the late sculptor/painter/filmmaker Ana Mendieta (who really did suffer from sexism when her more acclaimed and famous minimalist-sculptor husband, Carl Andre, was backed by some rich and powerful male friends and acquitted despite being convincingly accused of her murder), is discussed and shown here, and these women, along with many others whose work Leeson covers, clearly made art that was exciting, inspired, witty, and serious--work to which we should be happy and thankful to be exposed. But there is also work here that was overlooked because it frankly deserved to be, that was fairly passed over: performance pieces that live up to the worst stereotypes about that much-maligned medium by being so literal-minded and heavy-handedly symbolic that it's embarrassing; pretty, dainty art objects that resemble skilled handicrafts more than anything invested with the layers, uniqueness, and above-and-beyond thought that art requires. Rosler's shriller, less imaginative, and more clumsily done video work, Semiotics of the Kitchen, for example, is just a sort of poor woman's version of Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman. And where is the great Akerman--a little-known filmmaker and an artist much greater and lesser-known by far in her medium than the majority of its men--anyway, in a work about female artists who don't get the acknowledgment they deserve?

By near-fetishizing the overlooked and obscure in that way, the film risks not only ignoring important artistic figures and milestones but preaching to the choir, too. Even if you make the dubious move of restricting "art" to mean the fine arts (excluding, for one towering example, Patti Smith), there actually are some very successful-on-any-terms contemporary women downtown/gallery artists like Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, and Jenny Holzer, whose names are much more familiar in the wider culture than those of most artists, male or female. But all these women are lumped together by Leeson in under 30 seconds, with practically subliminal flashes of their work (none for Holzer) obligatorily flashed on, virtually dismissing them as "the successful ones" even though, as far as many of the people this film could potentially reach are concerned, they're every bit as unknown and in need of discovery as any of the subjects !Women Art Revolution has much more time for. I don't know if it's inadvertent or not, but in this way the film illustrates the depressing isolation of the art world--an isolation that is a result of, among other (sometimes more self-imposed) things, the misunderstanding a great many people have of art as frivolous and irrelevant, regardless of whether it was made by a man or a woman. If Cindy Sherman and Jenny Holzer are the biggest fish in a pond that gets tinier by the day, they're also the ones whose vaguely familiar names might entice the uninitiated in for a closer, deeper look.

But what Leeson is presenting here is, ultimately, not an outreach to the masses starving for the kind of engagement, ideas, inspiration, and new perspectives that are the long-forgotten importance and "usefulness" of art. !Women Art Revolution is an historical project, presenting a history as checkered as any other, but one that has too often been neglected and deserves to be incorporated into the frame of reference of anyone who cares about art. Its drawbacks notwithstanding, the film does let us see, examine, experience, and interpret for ourselves artists and art that have been excluded, not just from acclaim or success they may or may not warrant, but from consideration. Some of it is very fine, provocative, and interesting; some of it is just bilious, solipsistic self-parody. Some of the women artists here clearly have something to contribute; some are just the sort of self-promoting, second-rate windbag that the art world has always been and will always be full of. But that's for us to see and decide for ourselves, and that's the opportunity Leeson successfully affords us. She is, like the recalcitrant Martha Wilson, here (despite her own tendency to solipsism and navel-gazing, unhelpful musings making the film more of a drag than it needs to be in spots) less interested in the rule-making and prescriptive than in the documentation of a long, still ongoing conversation. Toward the end of the film, Dr. Krista Lynes, one of the art historians Leeson interviewed, who had been shown a rough cut of the film, says that the most important and useful feminist practice is to raise questions and not shut them down with tidy or exclusive answers. At its best, !Women Art Revolution engages in that valuable practice, raising interesting, nuanced, and difficult questions and leaving them open to a degree that means the film's effect will outlive its spottier parts and well outlast the time you spend actually viewing it.

THE DVD:

The DVD transfer of the film--at an anamorphically-presented 1.78:1 aspect ratio--is great, retaining without interruption (or overcorrection) all the different textures, whether celluloid or video (from 8 mm to camcorder to contemporary higher-def digital video) of all the different filming processes Leeson engaged in during her decades of documenting, interviewing, and exploring.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo soundtrack is crystalline and full, devoid of any distortions, imbalance, or sonic murkiness; the film's music and many voices are always both clearly audible and well-mixed.

Extras:The extras include three additional interviews: one with Leeson on creating the project; one with philanthropist Elizabeth A. Sackler, who has made feminist art her cause; and one with comic artist Spain Rodriguez, who created some of the drawn cut-ins we see in the film and who drew the eye-catching artwork for the DVD. There is also a featurette on RAWWAR, the installation/website that is !Women Art Revolution's companion piece, designed to encourage artists to form a virtual grassroots community. There are also two theatrical trailers for the film.

FINAL THOUGHTS:!Women Art Revolution is a mixed bag by necessity, documenting as it does a rough, winding, chaotic history that's faced more than its share of uphill battles and is still in the making, ongoing and incomplete. If, in its mission to take an honest and recuperative look at the past few decades of feminist art, it sometimes gives too much of its attention to the solipsistic, narrow, sob-sister, dead-end factions of that movement in favor of showing us more of the really invigorating, accomplished, genuinely challenging, intelligent, and provocative work that it produced, that's a legitimate part of its mission to show us how it really was, warts and all. As with anything, you can't have the good without the bad, and any history of any avenue of art will, if it's honest, require a lot of patient wading through near-misses and second- and third-rate work to get to the good stuff (whose excellence, it must be said, can only finally be ascertained through comparison to other artistic efforts that didn't work). On the whole, even when it does direct its attention to artists of more dubious merit (who are sometimes entertaining personalities, if nothing else), !Women Art Revolution is sufficiently engaging and interesting, and rescues enough of the important work alongside everything that falls short, to be gladly and unreservedly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||