| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Turin Horse, The

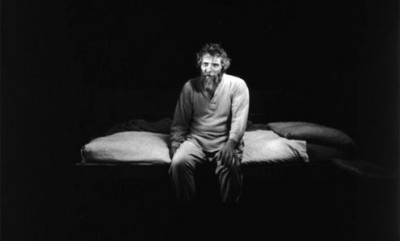

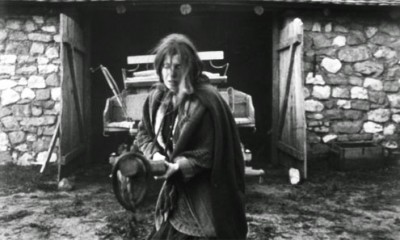

Please Note: The images used here are stills provided by Cinema Guild and are not taken from the Blu-ray edition under review.

"Even the embers went out."

Anything resembling conventional narrative is dispensed with quickly and tersely, at the very beginning of Hungarian film maestro Béla Tarr's superlative The Turin Horse. Following the silent, white-on-black opening credits, over a darkened screen, voiceover narration tells us, in a few sentences, the story of how, in Turin, Italy, in 1889, the German "God is dead" philosopher Friedrich Nietzche saw a carriage driver whipping his stubborn horse mercilessly in a public square, broke down sobbing, caressed the horse in frantic mourning, and subsequently spent the final 10 years of his life in calm, quiet, unproductive madness. "Of the horse, we know nothing," this affectless narrator informs us, and then we fade rapidly up on the first of the film's magnificently choreographed, remarkably extended shots, which lets us know at once that what we're about to see will show us what became of that strangely galvanizing animal. In a long, long track with not a single cut -- which moves beautifully from a frontal, leading view of the horse to tracking alongside the carriage driver back for a wide view of the rolling vehicle and then close in once more -- we witness the cruel master (János Derzsi, recognizable from Tarr's The Man from London and The Werckmeister Harmonies) and the horse whose suffering has just broken Nietzche rolling down a desolate path through a rising, very strong wind, back to the isolated rural home where the driver, apparently a widower, subsists with his daughter (Erika Bók, who as a child collaborated memorably with Tarr in his 1994 epic Sátántangó). It soon becomes apparent that for as long as they can really remember, this taciturn household has followed in lockstep a meager but precise daily routine. After the Turin incident, however, things are altered; something is off and unraveling in the stifling predictability to which this father and daughter have clung for so long that they know (and care to know) nothing else. The film is divided into the six days after the driver returns from Turin, and whatever you take "final" to mean in this context, these are six final days; The Turin Horse is an eschatological work whose intimate, tangible rendering of the apocalyptic is transfixing, frightening, and exhilarating in a way that makes most other stories and films with end-of-the-world conceits (and, truth be told, most other stories and films, period) look like child's play.

In lengthy, unbroken, miraculously blocked and gracefully, perpetually-in-motion takes, Tarr and director of photography Fred Kelemen (a filmmaker in his own right) take us into and through what feels like the minute-by-minute of the father and daughter's rituals of impoverished, labor-intensive subsistence. The first day, when the carriage driver arrives home from Turin, there is the putting away of the horse and vehicle; the weary father's shedding (with the aid of his subservient daughter) of his outer clothes; and the preparation of their permanent dinner menu of boiled potatoes, for which they do not possess utensils to eat and so use their hands as they eat in silent exhaustion. As the potatoes boil, the daughter watches through a window as the windstorm, now picking up force, rages and howls outside their hovel like it could blow everything away (this represents not the least of ways in which the film's superbly, meticulously designed sound is nothing short of astounding). After the two retire to their beds, the first day's disturbing break in the predictable misery is revealed: The father remarks to his daughter through the darkness that, for the first time in 58 years, he can't hear the woodworms working as he drifts off.

As the days succeed one another, the routine -- getting up, getting the horse and carriage out to go to work, drawing water (which now requires huddling through and fighting those terrible winds, which makes for spectacular moving images as we follow the daughter to and from the well), doing the washing, the morning shots of liquor to fortify against the backbreaking day, the potato meal in the evening -- devolves. The horse first will not move, then will not eat: no more going to work. A drunken neighbor stops by to borrow some brandy and delivers a searing monologue about how the centuries-long battle between the excellent, good, and noble and the forces of cruelty and meaninglessness has been lost; everything good has extinguished itself, burnt out, given up, and the end is nigh. A group of gypsies just looking for some water are greeted with xenophobic hostility by the two residents but leave a book with the daughter in exchange for the water, anyway; this book contains a history that recounts a corrupting and dwindling away of the "holy" and good much like what the neighbor described. The well is suddenly dry; the two attempt to leave, but shortly after disappearing over the hill, they reappear and return, defeated, as if something they've seen (and we haven't) beyond that ridge has shown escape to be a futile proposition. Finally, the windstorm stops, and there is silence and darkness; first the beast, then the water, and now the very fire that provides warmth and light have simply ceased to exist, the helpful laws of nature just running out, as if they were the very last flickers in their interloping, doom-saying neighbor's nightmarish jeremiad. The film's final image, the father and daughter sitting across from each other at the table, barely lit by some unknown source, with the father insisting that they must eat their meal of now raw potatoes (water or heat for boiling having disappeared) but no move from either of them to feed themselves, leaves you speechless, devastated. As far as we know, nothing else in the world is left, and the slow, long fade to black and the ultimate disappearance of the two figures as the film concludes represents, convincingly, the end of everything.

The paradoxical fact that this solemn, somber, single-mindedly doom-stricken tale is, as told by Tarr and his longtime collaborators -- Kelemen, codirector/editor Ágnes Hranitzky, novelist/screenwriter László Krasznahorkai, and composer Mihály Vig (whose music is always a vital part of Tarr's films and whose haunting, queasy, endless loop of cello/organ score here is, unbelievably and majestically, the very sound of apparently endless repetition in the process of winding itself down) -- a compelling cause for joy and celebration that leaves you full of rare, high wonder and even a very particular species of hope only attests to how very inadequate any written description (such as mine above) could be to the sheer physical presence of Tarr's films, which, in The Turin Horse perhaps even more so than in his other classics (Sátántangó, The Werckmeister Harmonies), are much less stories told or symbols to be interpreted than experiences that we live through. Tarr couldn't be described as a realist or naturalist, but the reality of the black-and-white images he and his collaborators create is beyond compare; he pushes cinematic time (you must adjust the artificial acceleration have conditioned us to expect to Tarr's much slower, agonizingly well-calibrated capturing of time's passing, moment by moment, on film), space, light, camera movement and composition to their utmost, creating unbroken scenes (a cut is a momentous event in a Tarr film; The Turin Horse's two-and-a-half hours is comprised of only 30 shots) that, in their elaborate movements and gradually shifting emphases, make for just about the most irrefutable, ineffably there onscreen reality you've ever seen. Tarr's exquisite utilization of the artifice available in his medium to create and breathe such extraordinary life into the world he's showing us could only come from someone at once incredibly inspired, talented, disciplined, and radically, unwaveringly committed to making his vision into something that we can almost touch and feel, will be indelibly marked by, and will not ever be able to forget.

Tarr has already achieved, through the best of his prior work, the status of a one-of-a-kind artist and world-class master; his is a singular, impossibly original voice that shares with its forebears Bresson (Au Hasard Balthazar) and Tarkovsky (Stalker) and its contemporaries Kiarostami (Certified Copy) and Ceylan (Once Upon a Time in Anatolia) an absolutely self-contained, definitive, impassioned, philosophically and metaphysically inflected view of the world whose natural outlet seems to be the cinema, though no other films anywhere look, sound, or feel quite like theirs. The Turin Horse is ostensibly the finale to Tarr's oeuvre, and however sad the prospect of no new Béla Tarr pictures to be floored by, he would be justified in leaving such a great, truly conclusive accomplishment as his final legacy. The realization of everything he has pursued throughout his artistic quest -- the imprinting of real, heavy time on celluloid in a way that allures and immerses; a steadfast, philosophically survivalist view of the sufferings of human life as innately dignified, even after all extraneous distraction, comfort, and hope have fled or been stripped away -- is cemented and furthered in The Turin Horse, and it seems certain that it could never be advanced or perfected to any greater extent than it is here. Most great films, especially those made since the very early years, are indebted in one way or another to the medium; they exist in continuity with what came before and what will follow in their footsteps. As The Turin Horse makes clearer than ever before, however, Tarr, like the aforementioned rarefied group of towering, idiosyncratic filmmakers, is timeless, completely apart, an artist who has bent his materials entirely to his will; in the exceptional case of a filmmaker like this, it's the other way around, and the cinema is indebted to him.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Typically for The Turin Horse's distributor, Cinema Guild, the transfer -- an AVC/MPEG-4, 1080p presentation of the film at its correct theatrical aspect ratio of 1.66:1 -- is a conscientious, painstaking work of beauty; the contrasts and solidities in Kelemen's transcendent black and white cinematography are impeccably conveyed, pristine at each and every split second (there are many, many dark moments, but no crushed-looking blacks or other distractions). But it's the good kind of pristine; nobody has blanched out (via overuse of digital noise reduction) the fine celluloid grain, so the feel of the film remains as cinematic as it possibly could for home viewing. It's perfect work from the closest-to-perfect American film distributor going right now.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 soundtrack (in Hungarian with optional English subtitles) offers two crystal-clear channels of sound (I didn't notice center-speaker sound, which seems precisely correct for this film and its sound mix) in a film from an artist for whom the aural couldn't be more important, and never more important than it is here. All dialogue, that relentless windstorm, and Mihály Vig's unforgettable endless loop of a score are all immediately present, rich, and full for our sober delectation.

Extras:--Hotel Magnezit, a very early (1978) 12-minute short film by Tarr, in which an aging, drunken, irascible man is hounded from a public hostel for his alleged crimes. The short works nicely as a sort of bookend, if The Turin Horse is, indeed, the director's swan song. If you haven't seen any of Tarr's early "proletariat trilogy" (very, very different -- claustrophobic social realism as opposed to awe-inducing vastness of philosophical/aesthetic scope -- from his later, much grander works), this makes for an excellent example of his style at the time and should enable viewers to contrast and compare what many of us see as a real split between early and later Tarr (though the director himself disagrees that there was ever a "turning point" in his work, as he and others go into in the other supplements).

--An unusual (but very fitting just because of its atypicality) audio commentary by critic Jonathan Rosenbaum which is only half-length (70 min.) but an outstanding case of quality over quantity if there ever was one. Rosenbaum, a top-notch, extremely articulate, cosmopolitan, and agreeable great figure of American film criticism (if you haven't read his Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia or his many other vital books, you ought to do yourself the favor) self-effacingly explains his commentary's brevity at the beginning, telling us that he was reluctant to posit himself as a singular, expert interpreter of Tarr's film without a contrapuntal speaking partner. He goes on, instead of commenting on the sequences rolling by onscreen, to perform what he considers the tenable and fair alternative: enlightening us with his riches of knowledge and insight on Tarr as a filmmaker, his individual works, and his reflective, serious, and mutable take on the evolution of the master's entire filmography from beginning to end. (There are plenty of great personal anecdotes, too, as Rosenbaum is a friend of Tarr's.)

--Press conference with director Bela Tarr and cast and crew of The Turin Horse, a 50-minute program, apparently produced under the auspices of the Berlin Film Festival (where the film was in competition), which features an international group of journalists interviewing principal cast and crew after having seen the film. It's odd and fascinating, this clash of very distinct worlds. Tarr is a genuine enigma, contrarian and strict with himself and others by nature, not a showman or publicity hound by any stretch, and the crew (including, among others, Tarr's creative and life partner Ágnes Hranitzky, DP Fred Keleman, composer Mihály Vig, and poor Erika Bók, a nonprofessional actress so perfect in the film but entirely unused to the odd publicity situation she's found herself in; she's charmingly but literally tongue-tied behind her microphone) are more or less equally reticent. But we still get lots of interesting, thoughtful, sincere responses (translated in voiceover for us by a pleasant-sounding Irish woman who sometimes halts to make sure she has the translation precise enough) to some often very convoluted questions (understandably so; the film is a pure visual/physical experience ill-suited to words, description, and explanation). In addition, Tarr reveals himself to have a suitably sardonic but openly smiling/laughing sense of humor one might not presume from his work.

--Tarr also shows his particular mix of humor and strictness in the 81-minute Regis Dialogue with Béla Tarr at the Walker Art Center (a supplement exclusive to the Blu-ray edition) with his interlocutor, the film critic/festival programmer Howard Feinstein. It's sometimes extremely awkward, with Tarr more often than not correcting his nervous, intimidated (and what serious movie lover wouldn't be?) admirer Feinstein, who runs five to 10-minute clips from most of Tarr's films for an audience and then poses related questions, many of which contain words and assumptions Tarr seems eager to challenge. But it's revelatory, both about the dearth of ways to discuss films like Tarr's in any conventional or even available terms, as well as of Tarr's unwavering, uncompromising adherence to his own integrity and what he considers his motivations for choices big and small in his creative/aesthetic beliefs and practices. Again, as in the supplement from the Berlin press conference, Tarr's tonic sense of humor makes his punctiliousness and insistence on precision clearly more a matter of genuine honesty than any meanness; he would be intimidating to talk to, but he also cares about communicating to the extent he finds truthful, and that comes through very well in this discussion.

--The film's U.S. theatrical trailer (it's always refreshing to see Cinema Guild's always true-to-the-film previews) along with a number of trailers for other Cinema Guild offerings.

--Yet another great American film critic, J. Hoberman, adds his erudite and learned take on The Turin Horse in an essay, "Brute Existence: The Turin Horse," included in a leaflet insert.

A (purportedly) final masterpiece from the great Béla Tarr, The Turin Horse is the most important, the most elemental film we've seen (or are likely to see) in a very long time. Its story couldn't be more simple or symmetrical; its intellectual, aesthetic, philosophical, and emotional implications, on the other hand, couldn't be more vast, mind-blowing, and devastating. In recounting the six days following an only-possibly-true incident in which Friedrich Nietzche supposedly broke down upon witnessing a carriage driver abusing his stubborn horse, never to recover, Tarr makes the carriage driver, his daughter, and the horse itself the center of his film, and these desolate, wind-whipped six days play out like the decline, the mirror opposite of the Judeo-Christian creation myth, each successive 24 hours representing one more step in the inexorable winding down, dwindling, and extinguishing of a blighted-beyond-repair world. That is an impossibly tall, portentous order for any artist, but Tarr (alone, I believe, among all living filmmakers) has the single-mindedness, unrelenting sense of gravity, and stringent, diligent, and true philosophical and aesthetic seriousness to accomplish it completely, sustaining the film's tone and internal logic impeccably throughout; despite what may at first glance seem the grimness or bleakness of such a vision, it's flat-out amazing, thrilling, and exhilarating to see it realized with such painstaking care and to such astounding perfection. Most reliable sources, including the director himself, insist that this really is the last we'll hear from Béla Tarr as a filmmaker (he plans to go into producing and will be starting a film school in the future), which, if true, is a tremendous loss for the cinema, though Tarr has left a legacy that will last for as long as anyone has still heard of the medium. But whether it's really his final statement as an auteur or not, The Turin Horse is a film to savor, a striking and irrefutable vindication for the idea of cinema as high art, and as close to a true, deep metaphysical/religious experience (and probably more so) as anything else that's ever been put to celluloid. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||