| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere)

"The contradictions soon explode, taking you with them."

The specific "here" and "elsewhere" of Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere), a film made anonymously by Jean-Luc Godard (Vivre sa vie, Contempt) and his comrades as part of a mid-'70s collective-filmmaking experiment calling itself the Dziga Vertov Group, are France in 1974 (the place and time when the film was completed and put together) and Palestine in 1970, when the film's documentary footage of Palestine-liberation military preparation was commissioned from the group by the Palestinians themselves and shot before that side's bitter defeat in the Six Days' War at the hands of Israel. What started out as a film about the Palestinian uprising, prematurely entitled Victory, was thus shelved for years, eventually to be subsumed by Ici et ailleurs, a work of lacerating self-reckoning, a systematic and relentless probing of why these images were really made, in what ways they were false and compromised (and even staged), and how their appearance of documentary "objectivity" made them even more shaky and duplicitous. An earlier Dziga Vertov Group Project had been Letter to Jane, a 45-minute piece in which Group founders Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin presented us with a single filmed image, a still photo of Jane Fonda (star of their own earlier film, Tout va bien), and dissected it ruthlessly in voiceover in a way that struck some as simply vicious, if not outright sexist. Those angered by A Letter to Jane might take some comfort from Ici et ailleurs (which is a better film in several respects, anyway); it shows that the Dziga Vertov Group was just as willing to turn that blisteringly radical critical scrutiny upon itself in a way that's more fruitfully provocative than beating up on naïve celebrities.

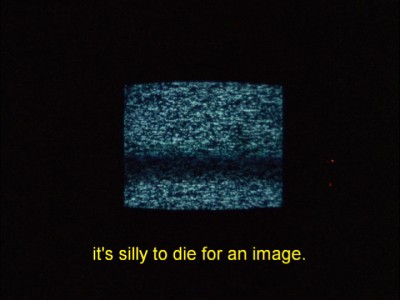

The voices we hear philosophizing, criticizing, and arguing are less easy to identify here than were Godard's and Gorin's in Letter to Jane, but their voices are doubtlessly included, along with those of Godard's creative/life partner and fellow DG Group member, Anne-Marie Miéville, and other active members of the group at the time the film was being made. The meaning of and connection between the images under discussion is almost entirely unclear, but the task here is to point up the true lack of simple connection and easily facilitated conclusion-jumping between oneself and any linked-together set of images. The point is to raise a question of clearly desperate importance to the politically engaged filmmakers and their medium: there is surely a connection there, between those (naïve? overly optimistic? merely self-serving and escapist?) shots taken of confident and passionate revolutionaries "elsewhere" (in another, very different place and, now, in another time) and the post-1968 slow, morose, progressive despondence and futility of what was to have been a new French Revolution, but how does one go about making that connection? Our narrators take themselves to task for being so disillusioned with the France of their time (their "here") -- encapsulated in dramatic scenes of a good union family in their living room watching manipulated, noisy, cascading, leveling successions of images on TV while working conditions and justice for labor inexorably deteriorates around them -- that they tagged along (rather uselessly, they seem to feel now) for someone else's seemingly more exciting, immediately possible revolution, one with which they could've better shown solidarity by keeping the flame burning at home.

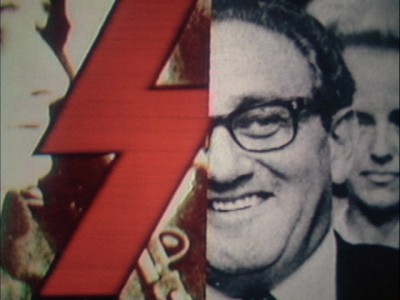

But the film is also an attempt to profit from such now-regretted escapist gestures made under the guise of solidarity. Using then very newfangled videotape and computer technology, the group imprints aphorisms ("learn to see, not to read," etc.) onto the screen and exploits the possibilities of slides and videotape editing to make disconcerting, asymmetrical, shifting single-image juxtapositions of, for example, Hitler, Nixon, Golda Meier, and a dead Palestinian child. The filmmakers themselves also appear in Brechtian dramatic sketches interspersed throughout, like the aforementioned TV-watching family or as a group of models holding up stills to a camera lens to demonstrate to us the way iffy connections between images are made to seem certain through film, obscuring the impossible-to-encapsulate reality. The different materials -- the now suspect documentary footage, the didactic sketches, the video/computer montages -- complement and magnify one another's resonant demonstrations that our hurry to make the connections between "here" and "elsewhere," "now" and "then" as we attempt to understand our world and its history puts us in danger of missing the real, never immediately discernible connections altogether, or even severing them: the film hypothesizes at one point that it was a succumbing to a TV-image-saturated world and its false, overly simplistic dot-connecting that led "Black September," the radical Palestinian liberationist group, to instigate the murderous publicity stunt at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. That was an act that the filmmakers, who wholeheartedly support Palestinian liberation from Israel's illegal settlements and oppression, find ill-advised and unethical, but that's beside the point; in their view, the most productive thing to do is make their film ask sincerely whether they were themselves complicit in this unconscientiously manipulated, overcrowded marketplace of images when they were trying to make Victory out of someone else's revolution , and whether they bear some responsibility for colluding with the widespread enslavement, even of revolutionaries, to mass-distributed images and their illusion of immediately powerful, effective communication.

This is all very heady stuff, and if you're one who wishes Godard had stuck to the Band of Outsiders/Breathless model instead of getting all rigorously political, be warned: Ici et ailleurs makes even Weekend and La Chinoise look like sheer frivolous "fun" by comparison. One primary motivation for the Dziga Vertov Group's existence was that no individual member's filmmaking practice be let off the hook easily, and, particularly if one is watching Ici et ailleurs from a sofa on a home screen, that hook snags us, too, since it's difficult to ignore one's resemblance in that context to the film's French family numbly watching ads and movies and horrific war footage on their television. But if you can appreciate Godard's submersion of his own personality/authorial voice into a communal, dialectical, cooperative, and committed approach to filmmaking -- his careful turning of his art to the service of new passions like the ethics of the image, how that translates into its aesthetics, and the ever-elusive goal of making and assembling images that don't hypocritically pretend to summarize a whole truth or offer the final answer to anything, but instead comprise just one small part of an ongoing, pressing question -- then Ici et ailleurs feels like a bracing, invigorating (and even, in its radically disorienting aesthetics, quite beautiful) first seed of a consciousness-expanding line of thought. Here, the power of cinema to convince is questioned and strictly harnessed, controlled, and directed to render the film a small but steady, decisive initial step toward finding the true, real, complicated connection between your "here" and someone else's "elsewhere."

THE DVD:

Olive Films presents Ici et ailleurs in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1, with a very conscientious transfer that preserves remarkably well the more spontaneous-appearing/naturally-lit textures of the Palestine documentary footage and all the film's other, more arranged and controlled uses of color, light, and shadow, with no edge enhancement and only traces of aliasing (mostly when titles appear, and even then only occasionally).

Sound:The Dolby Digital 1.0 monaural soundtrack (in non-optionally English-subtitled French and purposely un-subtitled Arabic) conveys the full range of the film's sounds, from narration and dialogue to music and the occasionally rougher direct documentary sound, as well as could be imagined. The film has a technologically modest approach to sound as befits its time and the ethos of its makers, but it's used brilliantly and wildly creatively, as usual, by Godard and team, and the sonic dimension of Ici et ailleurs is conveyed here in a way that's perfectly clear at every moment, with no audio overloading, distortion, tinniness, or imbalance.

Extras:None.

I wish every "think globally, act locally" bumper sticker could be replaced with a viewing of Ici et ailleurs, a filmed essay on the need to go much deeper than totalizing slogans (or sloganeering images) to get to the true, profound meaning of words like those, or images like the ones the filmmakers brought back from Palestine in 1970. To put it in a crude, simple way that doesn't do justice to the thoroughgoing depth of the film's examination of the politics and aesthetics of how to be a revolutionary filmmaker without being a tourist or a hypocrite: "here" is the world as it looks through your eyes, sounds to year ears, and feels in your skin; "elsewhere" is the world as experienced by someone else; and the assumption that seeing pictures of that other experience on television, in films, and in newspapers gets you directly from "here" to "elsewhere" is an extremely dubious one that our daily televisual experience, whose only volume levels are loud and louder, never stops dangerously reinforcing. Jean-Luc Godard and his fellow filmmakers in the Dziga Vertov Group put their foot steadily but all the way down on the brake of that kind of haste, mercilessly interrogating their own methods and activities as solidarity-granting documentarian-outsiders in Palestine and as actual citizens and residents of a France whose own revolutionary outlook seems unexciting and grim. The film is extraordinarily brief, lasting just under one hour, but its sonic and visual textures provide incredibly dense, rich food for thought; it's an hour of film that could lead to a lifetime of questioning received, conventional wisdom about cinema, politics, aesthetics, and what it really takes to see the world as clearly as possible before attempting to change it. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||