| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Numéro deux (No. 2)

"This film is not left or right, but in front of and behind."

Numéro deux (No. 2) is a film manufactured and assembled (these terms are fitting, as we'll see) in 1975 by Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless, Film Socialisme) and his longtime comrade in life and art, Anne-Marie Miéville. This was at the height of Godard's most self-exiled, anti-commercial, politically radical period, and Numéro deux crystallizes in its purest, most intoxicating form the sensibility that insisted, in La Chinoise, on informing us via intertitle that we were watching "a film in the process of making itself" and that started off the scintillating Tout va bien with a montage of close-ups on checks being made out to the film's various stars and departments. Godard's interest in rendering transparent what's usually wholly obscured in films (the means and conditions of production, the inner workings and financing and machinery), along with his analogous drive to slow down, elongate, and examine the complicated truth of what the majority of films takes for granted as something already transparent (the conditions of everyday life, work, love, sex, familial and other relationships, etc.), reaches a sort of zenith here, and the film thereby becomes one of his richest, most challenging and invigorating works.

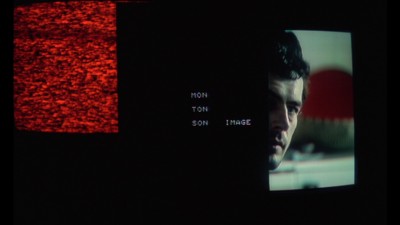

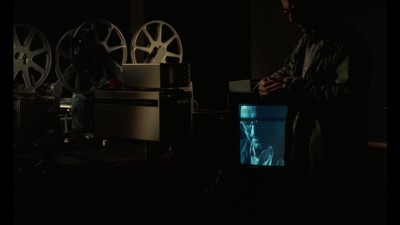

Numéro deux is comprised mainly of videotape images juxtaposed and layered to tell the film's "story" in startling, ingeniously suggestive ways, but it's bookended by scenes shot in the more traditional 35 mm, which record Godard at the self-contained film/video facility (an "independent studio" in the strictest possible sense) in Grenoble where he installed himself in the '70s upon exiting Paris (and narrative film) for good. There, surrounded by the monitors, projectors, and other filmmaking machinery in what he calls his "factory" (he likens it to other, very different "factories" like Mosfilm in Moscow and 20th Century Fox in Hollywood), the director delivers a monologue in which he details, among his other free-associating political/cultural streams of consciousness, the way he got the film we're watching financed by his onetime Breathless producer, Georges de Beauregard. Getting the money is a precondition to the film's (any film's) existence, and disclosing where it came from is an act compelled by the obsessive drive for elusive cinematic Truth that has haunted Godard for his entire career, an obsession that permeates ever moment of Numéro deux. What these shots of Godard, upon which the film opens and closes, hold together is a "story" -- played out inside of the two video monitors we have seen in Godard's studio, which appear sometimes as a single image, sometimes both monitors at once, and at other moments with one screen overlapping with or asymmetrically larger than the other -- involving a family that lives in one of France's high-rise public housing towers (HLMs). This multigenerational unit (one of the many possible meanings of the film's title has to do with reproduction -- first generation, generation "No. 2," etc.) consists of a grandfather and grandmother, retired leftists whose revolution failed (or did they fail it?); a unionized factory-worker husband and a housewife whose consciousness is being incrementally but turbulently raised by the rising tides of feminism; and the two children, Nicolas and Vanessa, who are precociously curious about matters social and sexual.

That story is refracted (or, on Godard's and Miéville's terms, clarified) through the duelling video monitors before our very eyes; the two screens and their various permutations create on the cinema screen a dense, teeming dialectic between one character's subjectivity and the others', not at all in the manner of Rashomon, which concerns itself with "what really happened," but in a way that tries to get at what this family's gender and sexual relations, work lives (whether recounted by grandpa or lived in the present by dad), and ages means to each one of them and to their lives on a moment-by-moment basis. When we saw them at the beginning in Godard's studio, the video monitors were simultaneously showing news and films, but the escapism of the movies and the leftist sloganeering of the May Day parade covered by the news program are both cataracts in the video eye, obfuscations Godard and Miéville mean to remedy by using the same TV box-sized video to capture the most mundane, everyday routines of family life. They then place what they've videotaped on the movie screen in patterns that reveal the inescapable political underpinnings and implications of every moment and every interaction in this least extraordinary, most germane microcosm of society, defamiliarizing the ennui-ridden household routines and bickering and holding all the quotidian activities at angles to each other that are breathtakingly revelatory; for example, the young wife's performing fellatio on her husband (Numéro deux is simultaneously one of Godard's most sexually explicit and least erotic works) and the grandmother's scrubbing the floor become, when aligned side by side in this way, similarly tiresome chores/actings-out of oppressive gender roles. And this strange, wonderful visual grammar hardly stops at juxtaposition: it brings an incredible significance to moments displayed as only one large image within the movie screen, and still other resonant significations are created when Godard and Miéville duplicate what we're seeing in two places on the screen (a sort of image-in-stereo) or use video's freer editing properties to superimpose one image over another.

Those are only a few exemplary impressions selected from the film's vast network of interlocking, positively and/or negatively-charged images, sounds, and themes; each sequence in Numéro deux is so loaded, it could be on its own the subject of an entire essay, as could the film's brilliant conjoinings and disjunctions of sound and image (which every Godard aficionado knows is one of his particular specialties) or its employment of apparently self-generated computerized intertitles perpetually in the process of altering. The film offers up layer after layer of substantive cinematic meaning-making for us to dig into and participate in. That the participation involved is unusually active is part of what makes the film so demanding and rewarding; even a tenth viewing would still leave a viewer with new stones to turn over and further impressions to come away with, and I found myself more eager than I usually am to immediately rewatch a great film that's made an unexpectedly deep impact. For now, though, I will content myself with ending on a claim that Numéro deux has one of the most hopeful (if not "happy") endings in all of Godard. The film's second bookend -- the closing image that takes us back into Godard's studio, where we are aware that all the images we've just seen have been put together -- is markedly different from the first one. This time, we find Godard slumped, asleep at his work, while on the soundtrack the housewife's dialogue (now playing on Godard's studio monitor rather than as its own image on the screen) continues as barely-visible quasi-voiceover, becoming a castigation of Godard (a middle-aged white male filmmaker who "tells other people's stories"), what he does, and the audience that "gives up their rights to their own story...and pay for it" upon the purchase of every movie ticket. Godard, awakening blearily, regards this image. But then another monitor flickers on, showing the little kindergarten-aged daughter, Vanessa, in the bath; as the dismal intonations of her literally and metaphorically constipated mother (the physical and the political having become by now, in this film, one another's inseparable companion) speaks of "today and tomorrow" and asserts that "I should be there [at Godard's place]," one turns one's gaze and looks, as Godard himself does, to this female child, wondering if her tomorrow will be less oppressive than her mother's today, whether she will retain the rights to and tell her own story and occupy her rightful place.

The film and its apparatus are brought to a close at the same time: The monitors are turned off, the audio mixing equipment shut down and covered up, there is a sharp cut to black (is this the "closing of the eyes of oppression" spoken of at this moment in the melancholy recitation on the soundtrack?), and then, after a few frames of blackness, the audio cuts to the silence in which we can now contemplate, before hurrying to take it in again, the film that perhaps brought Godard closest to realizing his quixotic dream of creating, within the compromised confines of the cinema, something completely honest, entirely true, and unequivocally revolutionary in every way.

THE DVD:

This is quite a nice presentation of Numéro deux; the 35 mm stuff comes through fairly well, with some but not a horrendous amount of digital noise reduction that doesn't irrevocably oversmooth the image. The video bits that make up the majority of the film are, of course, supposed to look like nothing other than rather primitive, TV-news-quality videotape, which they do in perfect keeping with the aesthetic intention. The difficult question is the aspect ratio: the film is presented here at 1.66:1, but that seems to only apply to the opening and closing scenes shot on 35 mm (not the intervening video scenes that make up most of the film and are, at any rate, never occupying the full screen). IMDB lists the aspect ratio at 1.37:1, but 1.66:1 for "final scene" (i.e., the opening and closing sequences shot on 35 mm); a foreign distributor called Intermedio Films has released it on DVD at 1.33:1. Whatever the intentions of Godard (which, being Godard, are quite possibly inscrutable in an intentional way), the discussion here (including screen comparisons at the two different aspect ratios) conducted by those more intrepid than I suggests, both visibly and in their commentary, that 1.66:1 is a perfectly valid, if not definitive, way to have gone.*

*A particularly large debt of gratitude is owed to Lee Spratley for his calling my attention to this entire controversy, as well as sharing with me a must-read, in-depth essay by David Bordwell that goes into excellent, serious, extremely thoughtful and careful detail on the matter.

Sound:In most of Godard's films, sound plays a more important function than usual, and the Dolby Digital 1.0 soundtrack on this edition (preserving the film's monaural sound, in French with non-optional English subtitles) brings Numéro deux's to us entirely intact: the oft-cacophonous, always multiple sonic layering comes through sounding just as it was meant to, which is to say not always crystal-clear, but free of any technical flaws such as distortion or imbalance to impede the aural intentions of the filmmakers.

Extras:None.

Highly Recommended. It would be misleading to claim that Numéro deux is Jean-Luc Godard's (along with his co-filmmaker here, Anne-Marie Miéville) most immediately enjoyable film (if any movie ever demanded multiple viewings, it's this one). But if one were to take into consideration the great director's own stringent, brutally uncompromising terms, it wouldn't be out of order to put it in the running for Godard's "best," most successful picture. Its formal rigor and inventiveness are absolutely stunning; at the technical level alone, it's more modern, more innovative, more apt to and transformative of the experience than any CGI, 3D, or green-screen you can think of. And its boundless creativity is all in aid of one of the most densely layered, least decisive yet most genuinely, deeply inquisitive/interrogative cinematic polemics on sex and politics and society ever made. It draws new lines where it sees oppressive homogeneity (part of the reason it's called Numéro deux is that it takes what appears, or is made to appear, as one monolithic image and sees in it at least two different stories), paradoxically blurring in the process any old, useless or obstructive lines artificially dividing those dimensions of life, perhaps rendering obsolete those commas I've just placed between sex, politics, society, etc., and requiring that we invent a new word that makes those "different," falsely divided terms simultaneous and one. Miéville's introductory voiceover ruminates, "It's not politics, it's sex.... No, it's not sex, it politics...." before demanding (of us, of this film, of cinema itself, of the world, So is it about sex or politics? Why is it always either/or?" The film that follows offers a densely layered, challenging, but finally, I think, very hopeful response: It needn't be, not if you look closely enough, think deeply enough, ask and continue to ask until you find the right questions, and have the courage of imagination and the ability to remake aesthetic convention that Godard and Miéville display so beautifully in this intellectually vivid, indispensable example of the very best kind of political cinema -- the kind won't let us ignore the urgency of its questions and implores us to seek the answers it conscientiously refuses to provide.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||