| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

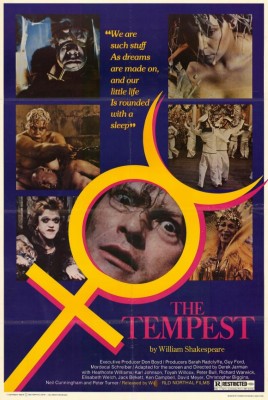

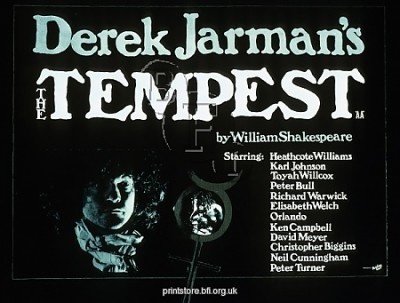

Tempest: Remastered Edition, The

Please Note: The images used here are from original or other promotional materials, and are not taken from the Blu-ray edition under review.

"This is a strange thing as e'er I look'd on." - King Alonso of Naples

"How beauteous mankind is! O brave new world/That has such people in it!" - Miranda

How do you follow up an apocalyptic punk-rock satire that seemed to offend even more people than A Clockwork Orange, up to and including the purist punks whose energy it was inspired by and meant as a tribute to? If you were celebrated British underground auteur Derek Jarman in 1979, having just shocked and rocked the world with your prior year's film, the scorched-earth, anti-royalist comic nightmare Jubilee, why, of course, your next step would (un)naturally be to take on Shakespeare! Jarman made his name as a radical artistic and political activist for gay rights, AIDS awareness/treatment, and opposition to Margaret Thatcher's privatization schemes in the '70s and '80s, and one might suspect that he shared his creative origins and enraged aesthetic inspirations with the angry punk youth who saw no future. But Jarman was of a different generation than the kindred-spirited kids with whom he empathized, with their scowls and lacerating three-chord anthems, and he came from a fine-arts background -- painting, poetry, etc., all in some sort of continuity with the great art of centuries -- that he never could bring himself to renounce as a dead, useless, or oppressive tradition. He had to make his own solution, create something relevant and progressive without tossing the artistic treasures of centuries; rather than cynically slumming and bandwagon-hopping (though that is what he was accused of in some quarters for Jubilee) or succumbing to nihilistic, everything-in-quotes postmodernism, Jarman found his own third way, one that saw the history of great painting, literature, and music not as the property of the status quo, but as a tradition of invaluable, anticonformist beauty to be reclaimed for the misfits and outcasts and breathed fresh life into by any means necessary, even if that meant offending self-appointed cultural gatekeepers/morticians and self-styled, denunciation-addicted rebels alike. And so his Tempest navigates its uneasy, fascinating, often brilliant and beautiful way between those two arid shores, striking flamboyant, unpredictable poses all along its course as it retells Shakespeare's story of the duke, Prospero -- betrayed by his brother, rejected by the King of Naples, and exiled to a seemingly cursed island -- who, with the aid of patience and magic, conspires to return things to the way they should be and grant his daughter her rightful place in the royal lineage.

Jarman gives us an unusually hearty and youthful Prospero, casting his comrade, '70s graffiti artist/poet/playwright/conjurer Michael Hillcote, as the exiled duke, who as the film opens is tossing and turning in his sleep as we see, in a beautifully filmed gray-blue, handheld abstraction of a ship tossed and turned in the sea (Jarman collaborates here with cinematographer Peter Middleton, who also shot his earlier Jubilee and Sebastiane), his nightmare vision of the tempest he has conjured up with the aid of his supernatural servant, a fairy or "airy spirit" called Ariel (long an up-for-grabs role, gender-wise, here played by earring'd male actor Karl Johnson (Rome, Hot Fuzz, Prick Up Your Ears), dressed in a futuristic white suit and gloves like he's ready for a night at the chicest disco in town). Prospero has spent all his time, for a very long time, poring over his magic books and incanting amid his patterned arrangements of candles, half-madly plotting ways he can use spells, divination, and Ariel to somehow ameliorate his break with King Alonso (Peter Bull, Tom Jones) who passed him over in favor of Prospero's scheming brother, Antonio (Richard Warwick, If....) for the privileged dukedom, denying Prospero's daughter, Miranda (Jubilee's sinisterly lisping girl-woman Toyah Willcox, here sporting a no less punkish 'do of straggly dreadlocks, along with a stripped skeleton of a period dress that looks like something out of vintage Vivienne Westwood), a future in the royal hierarchy. Miranda and Prospero have languished in their rundown, abandoned castle on the remote island with an Igor-like man-child servant, Caliban (Jack Birkett, who played the punk-assimilating mogul Borgia Ginz in Jubilee), the son of a witch, Sycorax (Claire Davenport), who had ruled the island and kept Ariel captive and tortured until Prospero arrived to set him free, vanquish the witch, and enslave Caliban in his turn. But Prospero and Ariel have now waylaid the royal boat returning from the marriage of the king's daughter in a faraway land, bringing its passengers to their lonely island in an attempt to right the wrongs done to Prospero and his daughter and save the misled king from Antonio and the king's brother, Sebastian (Neil Cunningham, The Draughtsman's Contract), who he and Ariel can see intend to kill the king and usurp the throne for themselves.

The first of the drowned ship's passengers to arrive is the king's grown son, Ferdinand (David Meyer), who emerges from the sea fit, wet, and naked (this bit is exclusive to Jarman's version; the camera notably takes its time, like Paul Morrissey photographing beefcake Joe Dallessandro for an Andy Warhol film, on leisurely views of Ferdinand's nude ambulations). He makes his way to the castle, promptly catching the eye of Miranda and incurring the wrath of Prospero, who shackles him and puts him to work. Miranda and Ferdinand flirt as best they can as he performs his forced chores; meanwhile, Prospero and Ariel, using their magic, can see everything: that the king and his entourage have arrived on the shore; that Antonio and Sebastian are plotting to kill the king as he mourns what he believes to have been Ferdinand's death at sea; and that Caliban has fallen in with two drunken sailors who've also washed ashore, with whom he is plotting to kill his hated master Prospero. Prospero begins to warm to Ferdinand as Miranda falls in love with him, his heart softening on behalf of the daughter he loves above all; Prospero and Ariel use magical trickery to make short work of the schemes of Caliban and his two new friends. Finally, the king arrives, Prospero and he make his peace, the bad brothers are defeated, Ariel has earned his freedom and is no longer the servant of anyone, and Miranda and Ferdinand can be joined in marriage, they and their good and just fathers living happily ever after.

A lingering eye for the well-proportioned male nude isn't all Jarman's film has in common with those made by Paul Morrissey under the aegis of Warhol; his performers may be reciting Shakespeare, and rather well, too, but the way he blocks scenes and directs actors intentionally creates a certain amount of dead air, eliminating any confusion about whether or not there's even a trace of impulse toward realism. No, it's an insouciant revelry in artifice that Jarman is after, the willful pursuit of what any stuffy Shakespearian purist would call anachronistic; if the performing style and the tempo and tone of things are Warholian, the painterly tableaux in which the story occurs seem to have been provided with ritualistic, quasi-occult props by Kenneth Anger and cheap-antique/secondhand-chic production design by the same Jack Smith who, in his notorious, classic 1963 avant-garde pop-art film Flaming Creatures, one-upped Scarlet Empress director Josef von Sternberg, the master of too-muchness himself, with an overstuffed, rotting-glamor mise-en-scène. (The actual art/production design for The Tempest was is a miracle performed by Ian Whittaker and Olivia Sonnabend, who also join forces with Jarman and Middleton to aptly artificialize the film's "authentic" exteriors, which were shot at Bamburgh castle on the northeastern English island of Lindisfarne.)

All this carefully sustained artifice leads up to and culminates in the wedding scene itself, which is something to behold. Here, we're in an over-florid Jarman pastiche of MGM Technicolor, and the "brave new world" the just-married Miranda speaks of with true joy (true joy being what this entire sequence is redolent with, despite, or maybe because of, its elaborately conjured air of drag-show camp decadence), the one that she and Ferdinand and Ariel are entering into as their increasingly somnambulic elders pass into the sleep of the bygone and outmoded, is apparently some extravagant gay nightclub with a floorshow of choreographed sailors (complete with jaunty WWII Navy uniforms, neckerchiefs and sailor caps and the whole bit) who part like a sea after they've finished their number to make way for a royally (one might even say queenly) decked-out grande dame torch singer, famed American expat jazz/blues chanteuse Elisabeth Welch, tenderly serenading all "the boys" with her signature tune, "Stormy Weather." This scene, lovingly detailed in all the thrift-shop glamorousness Jarman and crew can muster, choreographed and shot like some homemade study of Busby Berkeley/Vincente Minnelli style, is faithful to Shakespeare in that it fills the required "happy ending/marriage/closure" slot in his intended narrative structure, but it's utterly unique, a happy ending à la Derek Jarman (one of the few happy endings in any of his films), and it alone makes having this Blu-ray in one's movie library a very appealing proposition for any lover of art films.

Jarman was certainly an irreverent presence, both as an artist and as an individual in the world, but his Tempest, as radical, stylized, and ecstatically artificial as it is, maintains more than sufficient reverence toward and fidelity to Shakespeare to count as a "real" adaptation of the play done by someone who admires it, not a parody, travesty, or wholesale re-appropriation. It is rather anyone that has turned Shakespeare into an godlike "genius" and a sanitized, prescribed bore -- the provenance of "cultured," conservative people always pining for a more severely orderly past they imagine was better -- that Jarman reserves his irreverence for, and his film makes a very convincing case that Shakespeare's work lives on, still relevant, something that was forward-looking at its time and perfectly fitting to bring along with us into our own future, our "brave new world." Jarman was a great pessimist, too, and you can also take The Tempest that way, as the last, deliriously laughing gasp of something great, the kind of impassioned and ambitious and vital culture that an increasingly reactionary, unfeeling, and unthinking world no longer deserves; the long, slow, painful cultural death represented by the onslaught of Thatcherism, and his discouragement over it, were certainly topics on which Jarman was vehemently outspoken. But if this Tempest is the filmmaker's checking of Shakespeare's vulture-pecked corpse for any remaining heartbeat, he does, indeed, get those last few precious drops of vibrant blood out of it, creating one of the liveliest, most engaging and intelligently provocative presentations of Shakespeare you're ever likely to see. At heart, the aesthetically daring Jarman was an idiosyncratic traditionalist who was always keenly aware of the multitude of great artists that preceded him, all the way back to Shakespeare and beyond. He knew that centuries can't keep kindred spirits apart, and for all we know, the late Jarman (who died of AIDS in 1992) and the Bard himself are up there somewhere together now, their arms around each other's shoulders, looking down and laughing at all the squares who want staid monuments to the great plays instead of something that dare, as Shakespeare's works did in their time, to be recklessly imaginative, ebulliently tacky, truthful instead of realistic, alive, and profound.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Kino Classics presents The Tempest at its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio in an AVC/MPEG4-encoded, 1080p-mastered transfer that retains the raw, half-chintzy charm of its source. Pristineness was never Jarman's aesthetic goal -- it was usually more like homemade, tattily glamorous, homoerotic pageantry, and that's reflected in his technical choices, which for The Tempest, as often for Jarman, meant 16 mm blown up to 35, rendering all the visuals a sort of smudged-lipstick blur that fits his take on the material to a T. That particular texture is well-preserved in the transfer here, as are all the particular colors (those blue-filtered beach scenes in particular) that are as well-defined and bold here as you've ever seen them. The washing-out of VHS (and, to a lesser extent, non-remastered standard-definition DVD) tended to take Jarman's specific, rough-clashing-with-refined technical side to too far a visually inscrutable, messy extreme; balance is restored with this release, which presents the film as close to its best-projected state as possible.

Sound:This release's PCM 2.0 soundtrack preserves the film's original monaural soundtrack to the fullest extent, but it's clear that the film has rough sound in its original source; it's the element that most clearly reflects its humbly low-budget circumstances of production. There is variation in the levels that make some dialogue sound swallowed-up and difficult to hear, whereas other dialogue (often in the very same conversation; it depends on how well each actor's voice is being recorded) is perfectly clear. There is also slight distortion on many spoken "s" sounds. This problem is restricted to dialogue, however; ambient sounds and music are relatively clear, balanced, and undistorted, and if you're either already familiar with the spoken lines or, like me, find Shakespeare's poetry easy to infer the meaning of through the words and rhythms you do catch (despite not understanding every spoken word even under the most crystal-clear audio context), then it's a noticeable but not insurmountable problem.

Extras:The supplements included here take us back for a rare glimpse at Jarman's early-underground, avant-garde, pre-feature filmmaking career with three fascinating short works made well before Jubilee earned him his (relative) international fame: "A Journey to Avebury," (1971, 10 min.) is a series of static shots (with rare, punctuating, beautiful zoom/pan movements), mostly of the Stonehenge-like Neolithic monuments of the titular region of England, that recall nothing so much as American avant-gardist James Benning's "landscape films." The two other shorts, "Garden of Luxor," (1972, 9 min.) and "Art of Mirrors," (1973, 6 min.), both eerie, half-comic, half-decadent meditations on artifice and sex that conflate the distant past and their immediate present in jarring ways meant to make sparks fly, feel more like precursors to Jarman's better-known/full-length work.

With his Tempest, Derek Jarman skillfully and inspiredly shows us how to "subvert" a classic of Western civilization without merely thumbing one's nose at it; he starts from a deep understanding of Shakespeare's final masterpiece, then filters it through his deeply sexually and politically critical view as an artist/activist from the then truly risk-taking gay subculture, in a way that renders the film less a subversion than an edifice erected upon a Shakespearian foundation that's shown to be as conducive to Jarman's lushly-colored, outrageous, proudly gay (in both the literally homoerotic and "sensibility" meanings of the word) interpretation as it has been to the thousands of others over the centuries. The magical, incantatory, haunted-house, fairies-and-pageantry side of The Tempest is the one Jarman focuses most tightly in upon, which is exceedingly appropriate to the medium: the visual artifice thus allowed for (even and especially in the color-filtered "natural," exterior scenes) makes for a stunningly eye-catching affair. The film's climax is precisely that: an aesthetically orgiastic, anachronistic, yet technically very faithful rendition of the play's matrimonial happy ending in which Jarman draws, just like Prospero calling in favors from his "fairy" Ariel (here played, of course, by a lovely/androgynous man), upon the queer-underground spirits of Jack Smith, Andy Warhol, and Kenneth Anger (and, no less, the more aboveground decadent lavishness of Visconti and von Sternberg, and the sensuous color-coding of Hollywood musicals) for a finale that cinephiles of all stripes, sensibilities, and orientations will experience as nothing less than visually and aurally orgasmic. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||