| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

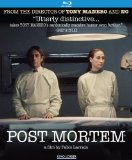

Post Mortem

The quietude of certain films, their calm contemplation of troubling events, can be extremely disturbing and devastating, even more traumatizing than eye-averting graphic violence. Such is the case with Pablo Larrain's (Tony Manero) 2010 picture Post Mortem, a political allegory set in Santiago, Chile during the horrendous, mass-murdering 1973 military coup that overthrew that country's elected socialist president, Salvador Allende, and installed in his place a brutal dictator, the notorious (and, quietly, U.S./CIA-abetted) general Augustin Pinochet. Coolly, stoically eliding the actual Pinochet bloodbath to show us the "normal" lives that went on around it, the passively complicit state of mind of the "apolitical" portion of the Chilean citizenry, and its awful aftermath, Post Mortem dramatizes a few days in the absurdly quiet life of a middle-class civil servant right at the crucial moment in which Allende was assassinated, and his adherents (or even, McCarthy or Stasi-like, those suspected of being left-wing) hunted down and "disappeared" by Pinochet's paranoid, mass-murdering militia. But the film's purpose isn't to give a history lesson; it employs the events of 1973 in a way that resonates much more strongly than it would were it merely a true-story, exact date-and-place-based reminder of the immediate players, the Pinochets and Allendes and the aggressors and victims, meant to inform and educate us on the facts of the '73 coup. Instead, it assumes at least a passing familiarity with that remarkably ugly moment in recent history and goes deep, much deeper than is comfortable, into the connection between the other, luckier, more comfortable persons involved -- the silent majority who "mind their own business" and do nothing while such atrocities take place. What makes the film so terrifying and troubling is its measured rationality -- the detached, nonjudgmental precision with which we are shown how the routines and distracting personal desires and dramas of its protagonist not only keep him at a comfortable remove from the violent suppression being openly enacted in his world, but gradually make him directly complicit in it (though, like the proverbial frog in the gradually heated pot of water, he remains blissfully deluded and conveniently ignorant of his role). That is to say, the person at the center of Post Mortem, whose extremely typical passivity and ordinary self-involvement lead him without thought or intention to be part of a brutally repressive political regime, could very easily be you or me were we in his shoes.

This sympathetic, anonymous, culpable individual is called Mario (the excellent Alfredo Castro, who also starred in Tony Manero), and he is by occupation a transcriptionist who sits in on and helps record autopsies, a tidy clerical vocation that allows him a comfortable existence in a nice part of Santiago, where of an evening he watches Pinochet's tanks roll by out of the windows of his sitting room before heading out to water his plants and possibly get a glimpse of his alluring neighbor across the street, an aging showgirl named Nancy Puelma (Antonia Zegers), to whom we see him finally get up the courage to go backstage and introduce himself after a performance he's enthusiastically taken in. She's just been castigated by her boss, who's throwing her over for a younger dancer, and her shattered ego leads her to accept a ride home from the rather pathetic-looking, stooped Mario -- hardly the Romeo such a diva would normally demand. On their way, however, they run into a Communist Youth march, and Nancy is beckoned out of Mario's apolitical company at the insistence of a handsome young man (Marcelo Alonso) participating in the protest, who's apparently a left-wing comrade of hers. An abrupt cut then takes us to the dim, sterile autopsy chamber where Mario does much of his job; he's tapping out the statistics, observed and dictated by his colleagues Sandra (Amparo Noguera) and Dr. Castillo (Jaime Vadell) on the corpse currently laid out atop the dissecting table. It's identified as Nancy's body, but her death has not been a violent one, like so many that this team of officiators is seeing these days of Pinochet; her diagnosis is protein depletion, i.e., starvation. The rest of the film recounts what has transpired between Mario and Nancy in his private life and between Mario, Sandra, and Dr. Castillo in his professional life during the intervening period that has bridged his meeting of Nancy and this later moment, in which he impassively participates in the official recording of her death and where the personal and the political finally show themselves, despondently but irrefutably, to be one.

Mario's involvement with Nancy is sweet, tentative; he's a nebbishy little man who lives a simple, stifled existence, and his flirtations with the vulnerable Nancy, whose professional stature and political allegiances are both in severe jeopardy at the moment, are something encouraging and sort of tender that we all like to see -- an underdog winning over the heart of a beautiful woman, "out of his league," who reveals herself to possibly be down to earth and human just like him, and understanding of his odd, isolated existence. But his good, shy, loving side -- his genuine concern for Nancy's well-being after a raid on her home by Pinochet's men leaves her not just vulnerable but desperate -- turns into an equally understandable but not so sweet jealousy when Mario discovers that, despite her free-love dalliance with him at a weak moment, she's still devoted to the young man from the Communist Youth, her longer-term lover, who now also needs Mario's help; like Anne Frank, the two of them need the quiet neighbor to hide them from the certain death that's seeking them out for no better reason than their politics. But Mario's personal feelings swamp any shred of awareness he may have of the urgent, immediate political situation; this is in contrast to his more worldly and knowledgeable coworker, Sondra, whose dating of other men has made Mario resistant to her deeper feelings for him, and who has become increasingly sickened by the coverup they've all been ordered to participate in as the murder victims of Pinochet's crackdown pile up around them, awaiting falsified reports on their cause of death. Mario has so little in the way of awareness of the world around him that his naivete extends, despite Sondra's more wised-up doubtfulness, to automatically supporting the official ruling, handed down by the military doctor who now acts as head of their workplace, that the corpse of President Allende (which arrives without fanfare on their dissecting table amid all the other carnage) was a suicide, not an assassination. (As another example of the film's relevance to the present and avoidance of time-capsulism, this same suicide-or-assassination controversy still rages in Chilean society nearly 40 years later.) As Mario's seemingly benign indifference -- his focus on his own life and careful steering clear of politics -- starts to reveal its true nature, we begin to see that it may be this innocuous, funny, lonely little man who'd just rather not get involved, and his adherence to that default-apolitical stance, that holds the key to Nancy's subsequent mysterious arrival in the autopsy chamber.

The style and structure with which Larrain tells the very disquieting story of Mario and Nancy is something beautiful (if not at all pretty) to behold. We've seen stark, slow-measured, calm, and matter-of-fact naturalism done equally well and perhaps even more finely by some of the director's own comrades in a relatively recent, glorious South American New Wave that also includes Peruvian brothers Daniel and Diego Vega (Octubre) and Argentinians Lisandro Alonso (Liverpool) and Lucrecia Martel (The Headless Woman). But Larrain has a special talent for it, and an original motivation for applying it in Post Mortem, which is a work much more explicitly historical/political (and politically implicating of the audience) than those of his great peers. Just as Mario, Sondra, and Dr. Castillo make precise, measured, emotionally removed cuts on the unfortunate corpses whose underlying truths it is their job and official duty to reveal, so does Larrain (along with editor Andrea Chignoli and cinematographer Sergio Armstrong, whose 16 mm anamorphic shooting and unblinking-stare framings, compositions, and long takes lend a documentary immediacy that, incongruously but marvelously, never loses its ice-cold edge) dissect with calm precision Mario's invisible, passive, but extremely consequential slide from indifference to cruelty. The discomfiting truth that the film's own dissection reveals, without a single second of hysteria or preachiness, is the insidiousness, the latent cruelty of indifference, the indifference of nice people who just go about their business and assume their own goodness, ethics, and morality while ignoring and failing the pressing moral/political questions and obligations visible all around them.

The film's final, very long, unmoving take creates unusually effective symbolism, played out wisely with zero overemphasis or announcement in a manner so steady and deliberate that it produces tremendous anxiety. It closes the film on our eminently relatable protagonist in the midst of an action, taken just as punctiliously, quietly, and indifferently as all the other actions in his life, that represents his own destructive, ostensibly ignorant but actually aggressive shuttering of the persecutions and murders he's idly looked away from while sitting on the fence -- a refusal to "take sides" which we gradually see not as some delusory "neutrality," but as his blank-faced shirking of his own responsibilities and allegiances, his own unavoidable involvement with the violent and ugly state his nation has come to. But that's not all: Mario's final, devastating, stone-faced act, done with as much calm, inevitable assurance as if he were just out watering his plants, also embodies with chillingly evocative perceptiveness the mental act most of us engage in when we bury or shut away the injustices that don't (yet) directly affect us, whether you're talking about the ordinary French citizen during WWII with nothing in particular against the Jews, a post-Soviet East German with nothing in particular against those who questioned the totalitarian Communist state, or the ordinary 20th-century (and beyond) American with nothing in particular against African-Americans (or communists, or gays, or Muslims, etc.). It demands that we observe ourselves and our own lives, which we tend to think of as harmless (because we don't intentionally, directly harm anyone), with new, clearer, scarier lenses. That probing, uncomfortable and all-seeing observational quality, achieved so acutely and with such relentlessness, means Post Mortem is not in any way a comforting or fun movie to live through. If you're looking for something deeper than that, however, it is an experience that's incredibly provocative, invigorating, galvanizing, narratively and aesthetically rigorous, and profoundly, inescapably, disturbingly meaningful.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

With the intentionally soft, slightly blurred look of the film (shot on super 16 mm, blown up to 35 mm, in mostly dimly-lit interiors), it's difficult to tell what "flaws" might be due to the transfer (an AVC-MPEG4/1080p, original aspect ratio (2.66:1) widsescreen presentation); there may be overuse of digital noise reduction robbing some scenes of important celluloid texture, but since brighter spots in the picture and the few daylight exteriors look very clean but not overly manipulated, with plenty of natural and appropriate grain, this may be due to the lighting. Otherwise, the picture quality is high, with solid blacks, good (though, purposely, not bright) colors, natural skin tones, and all sharpness available to the lower-fi way the film was shot, with no aliasing or edge enhancement/haloing.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 sound excellently captures (with no distortion, imbalance, or other audio defects) a sound design and mix that are actually magnificent, not lo-fi at all; a scene in which an audience applauds a spectacle onstage is just one example of the film's truly resonant, rich, and clear sound adding a you-are-there feeling that, unexpectedly, enhances and complements very well the film's (intentionally) less glitzy visual aesthetic.

Extras:Just the film's trailer (along with several others for Kino Lorber releases) and a stills gallery.

Post Mortem is a grimly effective political allegory that, ultimately, overwhelms with horror of the deepest, most unshakeable kind: the horror of recognition. Although writer-director Pablo Larrain has set the film very specifically and identifiably in his own country (Chile) during a period of horrendous, reactionary political terror (the 1973 overthrow of elected president Salvador Allende by Augustin Pinochet's military coup), the focus is on one individual so "ordinary," a clerical civil servant whose complicity is so silent and submissive, that we can't help relating to him, his instinct for self-preservation and his blind commitment to remaining within the comfortable, untroubled confines of his professional, bourgeois existence even as trouble roils all around and through his life. The utterly compromised places that this mild-mannered, responsible, eccentric but likeable man is taken by the hurricane-level political winds and his own overpowering, individual(istic) feelings -- just by doing nothing and ostensibly taking no political position during a political crisis -- are, as rendered so precisely by Larrain and the astonishing, terrifying central performance by Alfredo Castro, plausible to the extent that one easily, horribly imagines oneself doing just the same in his shoes. The film's stillness; its infinitesimal pace simulating the unfolding of real, mundane, ticking-clock bureaucratic time; and the unblinking, stoical stare of Larrain's camera make for powerful, slow, lingering imagistic impressions and responses that you'll be tentatively turning over in your mind for hours and days afterward. The film causes us unavoidably to contemplate just how frighteningly hard it would be to leave behind one's own reassuring, predictable routines and personal feelings to do the right thing, if they weren't the target in an aggressive, massive reign of terror -- how easy it would be to go with the flow and delude oneself that one is simply "neutral" even as every good, meaningful, and just principle and law is systematically violated. Post Mortem puts us on the spot and never lets us off the hook, but its power, the captivating, unsettling accomplishment of its filmmaking, cannot be denied. There are no scary monsters or villains depicted as such in the film; its monster/villain -- the passive, "apolitical" complicity relied upon by injustice and evil to thrive -- is so convincingly real, and so close to virtually all of us, that you may still want to leave on the lights after you've watched it. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||