| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

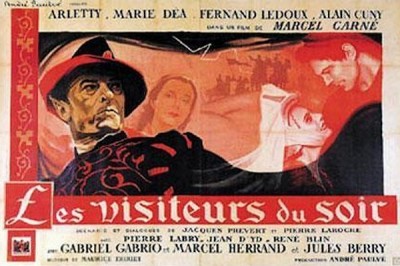

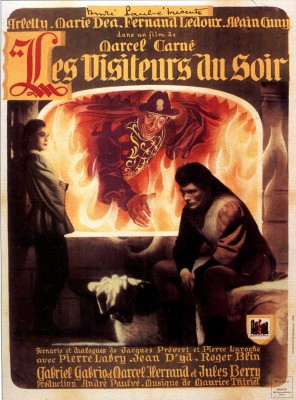

Les visiteurs du soir: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials and stills provided by The Criterion Collection, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

With such films as Le Jour se lève, Port of Shadows, and Les Enfants du paradis (Children of Paradise) studding his rich filmography, French director Marcel Carné proved himself time and time again to be master and perhaps (after Jean Renoir) the principal emissary of the particular "poetic realist" style that a confluence of production circumstances and talent brought out of France in the '30s. Now, Criterion has blessedly brought a somewhat less internationally well-known Carné film, Les visiteurs du soir (The Devil's Envoys in the English translation, but more literally The Nighttime Visitors), to a wider home-video audience, and none too soon: This long ago and far away tale of a planned royal betrothal disrupted by the envoys of the title, with all of the ensuing complications, stands right alongside Carné's other great films as a highly atmospheric, inexpressibly lovely picture, a story told with gentle seriousness (and not a little humor), and through a wider variety of stunning cinematic techniques than in any of his other most famous films (in addition to his usual unerring sense of composition and lighting). It doesn't quite threaten Children of Paradise's status as his magnum opus, but it does live up to (and, in some particular and breathtaking ways, even expand upon) Carné's other accomplished, beloved works.

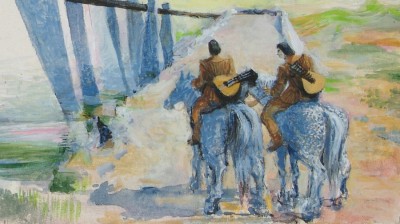

Visually and narratively, the film starts off as clearly a fairytale, and it never breaks the spell. When Gilles (Alain Cuny, The Lovers, The Milky Way) and Dominique ("Arletty," famed chanteuse/star of stage and screen, and frequent Carné and Sacha Guitry collaborator) -- two mysterious minstrels with old-style guitars slung across their backs who've been summoned by the baron Hugues (Fernand Ledoux, La Bête humaine) as entertainment for the engagement festivities of his daughter, Anne (Marie Déa, Orpheus) and her husband-to-be, Renaud (Marcel Herrand, Fanfan la tulipe) -- trot up on horseback to the baron's castle, before the drawbridge has even come down, they're already revealing that they're not all they seem by resurrecting a peasant's pet bear, which, he has mournfully told them, has been cruelly shot dead by the aristocrats reveling within. They may be the devil's envoys, each of whom we can infer has some sort of Faustian bargain in their past that they're doomed to pay off for eternity, but this opening act of kindness calls into question whether either of them are really as malevolent as would suit their master. Inside, Anne sits between her widowed, lonely father and her anti-romantic fiancé (who later actually forbids her from dreaming) as the nonstop amusements take place before the idle, feasting aristocrats. She's the only one not jaded enough to laugh and jeer when three little people have hoods removed from their heads to reveal deformed faces; she turns away from the exploitation, the first in many demonstrations of her sensitive, innocent purity. (These little people are the only ones who know from the beginning what Gilles and Dominique are, playfully teasing them and seemingly immune to their spells; if the medieval setting as a way to contemplate long-running philosophical and moral matters links this movie to Bergman's films via The Seventh Seal, these mysticized dwarves recall the troupe of little entertainers in The Silence.)

Anne's purity is recognized by Gilles, the less pragmatic and more susceptible to human feeling of the minstrel duo, whose eyes meet hers as he intones his ballad -- the beginning of a deep, true love between them that will cause all kinds of trouble and disrupt the prescribed amorous balance of the castle. (The film's chansons, written by screenwriter Jacques Prévert and Joseph Kosma, sound quite anachronistic to my ears -- i.e., not "true" medieval balladry -- but they're so moving and perfectly in keeping with the film's bittersweet, longing tone that it scarcely matters.) The witheringly pragmatic Dominique, who appears first as a boy (because of her dress) but unveils herself as a woman at the proper time, tries to keep the head-over-heels Gilles on the devil's path, reminding him that they're there to sow heartbreak, discontent, cynicism, and violence among these foolish mortals, not to go native and succumb to their naïve and mushy ways. She's doing her part for their nefarious mission by wooing Renaud away from Anne while at the same time promising Anne's desolate, world-weary father, who has a shrine to her late mother at which he worships nightly, an elusive cure for his loneliness in the form of her youthful, fresh femininity; the plan is to leave them both heartbroken and murderously jealous of one another. Gilles, however, drawn to the soft light of Anne's inner and outer beauty, strays far enough from the path that the boss himself shows up, on a suddenly dark and stormy night, to set things right. The version of Satan we get here (played with reptilian joviality by Jules Berry, Renoir's The Crime of Monsieur Lange) is one that's much more Devil and Daniel Webster than Exorcist, but he's still nasty and cruel, intolerant of peace and happiness, and unrelenting in his demands that Gilles keep to his bargain and that everyone suffer and be thoroughly disillusioned with love. Still, though he does his pernicious best to trick, coerce, and cajole everyone involved (one's heart stops when the naïve Anne has to try to make a deal with the devil, potentially dooming herself and sacrificing everything for her love), we feel he couldn't possibly triumph in the end, not against a love as surpassing as that between Gilles and Anne. He doesn't, but to call the film's end "happy" would be both an over- and understatement, since Gilles and Anne's ultimate fate is at once beautiful and terrible, making for a wholly lyrical denouement to a film that's as delicate and moving as virtually anything that's ever graced the silver screen.

Cuny and Déa do have beautiful chemistry, and as anyone knows who has seen his multiple other collaborations with Carné (the pinnacle being Children of Paradise), Prévert writes scenarios and dialogue that are full to bursting with emotion one can say is truly poeticized (Prévert is at least as well known to francophones as an actual poet as for his film work, and has long been France's permanent de facto poet laureate), but it's not just through the tender interactions between Anne and Gilles that we sense the blissful rightness of their being together or the sense that their made-in-heaven love can survive the opposition of Devil himself. It's there in the gorgeous mise-en-scène created by Carné and his frequent cinematographer Roger Hubert -- "poetic realism" is in the composition and lighting, and when we see the shadows of leaves, trees, and flowers cast by sunlight over the meadow and onto the lovers as they promenade near a fountain, talk earnestly and passionately, and lie in the grass, it's not just the words and body language but a sensual signal emanating from the entire image that tells us they belong together; it's a fact we drink in with our eyes and ears. The same extremely fine, chiaroscuro-imbued sense of shadow and light makes every scene just about as visually splendiferous and evocative as that one, yet it's always apt and in service of the scenario, without ever degenerating to the merely ornamental.

One element that distinguishes Les visiteurs du soir even from Carné/Prévert/Hubert's other collaborations is that here, they go beyond the poetic and well into the magical, using the supernatural threads available in the story to present us with some shimmeringly fantastical special effects; it's no surprise that Jean Cocteau was a friend of Carné's or that he was initially meant to collaborate on the project that become Les visiteurs du soir, since the film has the best of both the more strictly realist-atmospheric world of Carné films like Port of Shadows and Le Jour se lève and the brilliant cinematographic trompe-l'œil exemplified in Cocteau's artifice-reveling forays Beauty and the Beast and Orpheus. When Gilles and Dominique use their powers to make time stand still for everyone other than themselves and those whose hearts they are meant to ensnare (and, of course, the impervious little people), the film deploys magnificent slow-motion and exhilaratingly skillful trick photography to visually render the slowing and stopping of time. Elsewhere, when the Devil smashes a vase to the ground, it becomes a slithering clutch of serpents; and when he decides to taunt Gilles and Anne with the image of her father and her betrothed locked in a deadly duel, he shows it to them in the fountain, transforming the clear, rippling surface into an entrancing screen-within-the-screen. Tying it all together, the luxuriant pacing and additional "poetic" layer provided by editor Henri Rust's (The Wages of Fear) supple, instinctively perceptive montage makes the film's images themselves move like those two wandering lovers through the meadow -- blissfully relaxed, in no great hurry, but absolutely captivating. The film never feels heavy or dark, aiming instead for seamless ebbs and flows of tone that range seamlessly across the scale from the fantastical to the near-satirical to the storybook-romantic to the contemplatively philosophical -- but by the end (which has the best, most unexpected visual effect of all -- relatively simple but deeply affecting), it's accumulated an urgency, a tremendous gravity and significance that belie its lightness of touch. No less than The Seventh Seal or The Passion of Joan of Arc do in their own ways, it's a film that achieves something like mythological status, so that we take the lives, loves, and fates of its obviously invented, even archetypal characters very personally regardless, because they touch something close to elemental -- something that anyone living at any time, so long as they have open eyes and a working heart, can recognize and be moved by.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

An AVC/MPEG4-encoded, 1080p-mastered transfer presents the film (at its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.33:1) after an extensive restoration, and it appears here with an excellently retained amount of cinematic grain that, while always vital, is here truly indispensable. The film's full texture, in combination with the beautifully preserved range of darks and lights rendered in such a lovely way by cinematographer Roger Hubert, has obviously been rendered as conscientiously as possible for digital presentation by people who care and know what they're doing. There are multiple but very minor signs of print wear (some flicker, debris, and some rare light scratches), but they're utterly forgivable and never a real distraction; the film is amazing-looking, and that amazement has been done its due for this Blu-ray edition.

Sound:The uncompressed PCM monaural soundtrack brings us the original mono sound (in French, with optional English subtitles) in quite good condition. There are a few stretches of background hiss that never even comes close to overriding other sounds (I noticed these during dialogue scenes, and while noticeable, it was unobtrusive), but the aural layer of the film is mostly very nicely cleaned up, clear and resonant; music and sound effects are rich and crisp (background sounds of tweeting birds and burbling water during certain scenes, and a vital heartbeat sound effect near the conclusion, are very immediate and sonorous). Considering the film's vintage and the degree of restoration likely required, the audio quality is very good here.

Extras:--"L'aventure des visiteurs du soir," an approximately 40-minute program from 2009 in which writer and Carné friend Didier Decoin, archivist Andrew Heinreich, film historian Alain Petit, and journalist Philippe Morisson each contribute to piecing together a fairly thoroughgoing history of how the film came to be. (The on-and-off involvement of Jean Cocteau during the planning phases, as noted above, seems perfectly in keeping with the project Carné eventually was able to make, as does the initial idea to adapt Perrault's Puss in Boots in a medieval setting before dropping that in favor of what would become Les visiteurs du soir). The making of the film in both occupied France and the southern "free zone" during WWII, and the sticky, tricky business of pulling in and out of cooperation with German occupiers on one side and the resistant screenwriter Prévert and Jewish creative collaborators on the other, made for a complicated and difficult preparation and shoot, indeed, and a fascinating story is thus recounted here.

--The sleeve and 20-page booklet insert feature set designer Alexandre Trauner's very fetching drawings (made as an aid in planning Les visiteurs du soir), which couldn't any better embody the spirit of the film. The booklet also contains an essay by critic and novelist Michael Atkinson outlining the film's merits and placing it in its historical context of the Nazi occupation of France.

--The film's suitably excitable original theatrical trailer.

A work of overwhelming sentiment (never sentimentality) and sheer visual poetry, Les visiteurs du soir (The Devil's Envoys) comes awfully close to rivaling director Marcel Carné's deservedly most famous work, Les Enfants du paradis, for sublimity. A fairy-tale that meditates with unexpected, subtle profundity upon the meanings, essence, and complications of love, the film takes us back to 15th-century France and the romantic destinies of several couples, both meant to be and not meant to be, with the Devil himself, having sent two wayward emissaries (Alain Cuny and Arletty), finally showing up to pull the strings and set everything on his heartbreak-and-despondency-bound course. Love's triumph doesn't come easily (and the final, emotionally statuesque event and image exudes, at once, triumph and tragedy), but the film's true-hearted lovers (and we) are pulling for it, hearts in mouths, throughout. The beauty and elegance of the film's astonishingly delicate, complex visuals -- which use light and shadow and wonderfully well-integrated special effects to exquisitely render, by turns, the supernatural, the Romantic, the gothically grotesque, and the pastoral -- really do have to be seen to be believed. This is a multilayered movie for the ages, one that's simple enough to be grasped intuitively even by a fairly young child but profound, astute, and thoughtful enough to affect that same child in unimagined ways 10, 20, or 30 years later. Whether too young to have yet experienced romantic love, happily in or lonesomely out of love, or at a point where one has a history of love(s) to joyfully, sorrowfully contemplate, Les visiteurs du soir has a magical, illuminating light to shine on most any viewer. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||