| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

When Horror Came to Shochiku (The X from Outer Space / Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell / The Living Skeleton / Genocide)

- from Genocide (1968)

Inaptly titled, When Horror Came to Shochiku is a four-disc set of comparatively obscure Japanese movies all from 1967-68, films that connoisseurs of such outré fare have been asking about for decades. One of the four, The X from Outer Space (Uchu daikaiju Girara, 1967), is pure science fantasy, not horror by any measure, and it's the only one of the batch previously widely available to American audiences. Back in the 1970s it was a fixture of local TV stations' "Monster Week" afternoon movie shows, and later it was released to VHS and laserdisc, albeit dubbed into English and panned-and-scanned.

Conversely, Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell (Kyuketsuki Gokemidoro, 1968), appears only to have been released briefly to VHS in 1984, and that was on a limited basis by a video label specializing in porn.

The others, The Living Skeleton (Kyuketsu dokuro sen, 1968) and Genocide (Konchu daisenso, 1968), seem to have been shown only in Japanese-American movie theaters, and even then for just a week or so shortly after their releases in Japan.

All four emanate from Shochiku, a Japanese studio that rarely ventured into such waters, the company better known in the West as the home studio of directors like Yasujiro Ozu, Keisuke Kinoshita, and Yoji Yamada. The vast majority of more familiar kaiju eiga ("giant monster movies") and other sci-fi spectaculars were a specialty of Toho Studios, not Shochiku. But that genre's popularity and, in particular, its continued marketability abroad while domestically revenues were declining sharply industry wide after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, prompted similar efforts from all the other studios: Shochiku, Daiei, Toei, and Nikkatsu.

All four of Shochiku's efforts are extremely peculiar, and varyingly effective partly because they're so damn odd and often are surprisingly original. Each offers vividly imaginative visual concepts and/or unique story ideas, even when they're executed with toy-like miniatures or papier-mâché apparitions. Impressively and bafflingly, none is like any of the others, though they sometimes resemble films made by other companies. For example, while The X From Outer Space capitalizes on Toho's success with Godzilla & Co., the wild and wooly The Living Skeleton is very reminiscent of bankrupt Shintoho Studios' horror films from the late 1950s and early '60s, while Genocide anticipates Western world eco-thrillers of the 1970s, playing like a fusing of Frogs, The Swarm, and When Time Ran Out...

An Eclipse Series release (Number 37), When Horror Came to Shochiku is bereft of extra features but does offer short essays by Chuck Stephens on each film, all of which are presented in their original language (The X From Outer Space also includes a dubbed version) and are 16:9 enhanced widescreen.

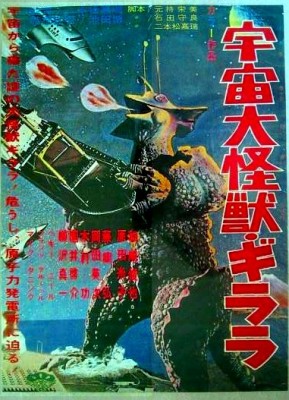

Though not well regarded among die-hard giant monster movie fanatics, The X from Outer Space has a uniquely peculiar charm that's hard to describe. It's a light-hearted film with a beguiling '60s-a-Go-Go sensibility. And a city-trashing monster.

The story concerns the happy-go-lucky crew of AABΓ, an evocatively designed space sled commanded by stern Captain Sano (Toshiya Kazusaki), with biologist Lisa (Peggy Neal), comedy relief communications officer Miyamoto (Shinichi Yanagisawa), and ship's doctor Shioda (Keisuke Sonoi), later replaced by Dr. Stein (Mike Daneen), also on board. They encounter an egg-like UFO that discharges blinking radioactive blobs, one of which will become the Giant Space Monster Girara (the Japanese title).

And what a monster it is. The creature looks less like Godzilla than a jamming Dizzy Gillespie wearing a party hat. Girara bellows incessantly (be sure to turn the sound way up when you watch this, so your neighbors can share in the fun) before being shrunk back down to its natural blob state - "girarium" (natch) which suspiciously resembles shaving cream.

Other than goofily memorable Girara, the Tokyo-trashing miniature destruction scenes are pretty ordinary and not done with the careful construction, lighting, and camera placement that sometimes can render them highly effective. Rather, the film charms for other reasons. While the 1954 Gojira continues to impress audiences with its sincere warning about the dangers of nuclear proliferation, the goofier appeal of kaiju eiga like Mothra (1961), Godzilla versus the Sea Monster (the latter a giant lobster, 1966), and Gamera vs. Giron (a monster steak knife, 1969) are much more representative of what really wowed nonplussed Western world audiences.

Shochiku's film takes the genre one step further into the Japanese Twilight Zone. With its incongruously festive musical score and title song, sleigh ride-like space flights, cocktail parties for co-ed astronauts on the moon, The X from Outer Space is Godzilla by way of Frank Tashlin.

One final note: Japanese genre films of this era often featured a token foreign co-lead in the cast. Sometimes there was a bona fide Hollywood name (Nick Adams, Russ Tamblyn, Joseph Cotten, etc.) but usually foreign amateurs who happened to be living in Tokyo (and were perhaps strolling past the casting department at an opportune moment) played these roles. Charming Peggy Neal enhances this as well as Hajime Sato's Terror Beneath the Sea (1966), but her best role was probably as femme fatale Mary in the epic Crazy Cats comedy Las Vegas Free-for-All (1967). Genre historians like myself have tried tracking down these gaijin actors for years. Writer Brett Homenick located Kathy Horan (Goke, Genocide) for an interview in the fanzine G-Fan, and in 2009 I was at last able to track down the elusive Ms. Neal. Regrettably, chronic ill-health has precluded the more extensive interview I originally planned, though I've been collating bits and pieces from our phone conversations over the last few years. Hers is a fascinating story.

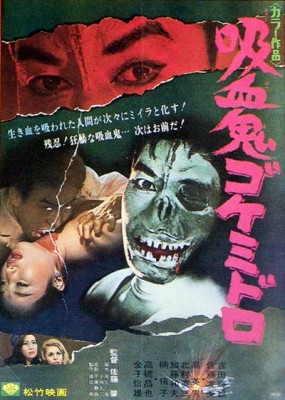

The best of this quartet unquestionably is the insanely imaginative Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell, notable for its evocative visuals and its unpredictable, dream-like story. Hajime Sato, who had a flair for such material, stylishly directed it.

During an anything-but-routine commercial flight from Tokyo to Osaka's Itami Airport the sky turns an inexplicable brilliant orange-red while a professional assassin, the effeminate Teraoka (Hideo Ko, who resembles a drag queen out of costume while attending mime school), announces his intentions to hijack the plane. Simultaneously, mysteriously disoriented black crows begin bashing themselves into the fuselage with bloody-red ka-thumps. And if that weren't enough, a bright yellow UFO flies by just before one of the birds crashes into the cockpit window, triggering a rough emergency landing in a desolate, rocky valley.

Survivors Sugisaka (Hiroyuki Nishimoto), the co-pilot, and stewardess Kazumi (Tomomi Sato) tend to the passengers, a nihilistic ensemble of High and the Mighty types, including unscrupulous politician Mano (Eizo Kitamura); scuzzy Tokiyasu (Nobuo Kaneko), an arms dealer willing to fob off his sexy wife (Yuko Kusanoki) to Mano to win a valuable contract; and American Mrs. Neal (Kathy Horan, in a role intended for Peggy Neal perhaps?), whose husband was killed in action in Vietnam following a gruesome head injury.

Teraoka flees the crash site with Kazumi as his hostage. However, a short distance from the wrecked plane they stumble upon the UFO, now landed and looking like a glowing gold pith helmet with four swirling tennis ball underneath. A florescent blue blob, apparently some creature, vertically splits open the assassin's forehead and slithers inside (looking like independently-minded sperm entering a vagina!), possessing and turning him into a bloodthirsty alien vampire who preys on the surviving passengers!

Condemned or merely dismissed for decades, Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell in recent years has been reappraised as a wildly imaginative and audacious work, particularly after director Quentin Tarantino expressed much fondness for it. Though hampered somewhat by a limited budget - the crash landing, for instance, is an unrealistic but vividly conceived miniature set piece - the film has many memorable moments, from its knocked-it-out-of-the-park prologue to its bizarre, apocalyptic conclusion, which writer Stephens amusingly describes as what George Romero might have done with Last Year in Marienbad.

Indeed, what all four films have in common (okay, less so with The X from Outer Space) applies to Japanese program pictures and genre films generally: they were made by sophisticated craftsmen and artists plying their trade in a (usually) unsophisticated genre. Compared to cheap American horror and sci-fi movies of the '50s and '60s, movies like Goke show a level of intelligence and good artistic judgment lacking in their far less ambitious American counterparts.

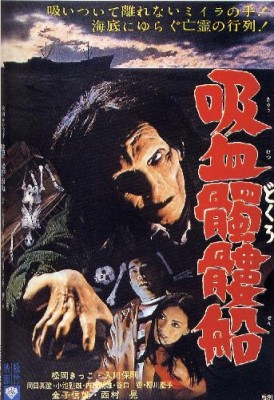

The venturesome The Living Skeleton is a vengeful ghost story similar to John Carpenter's later The Fog (1980). There are several striking similarities, to the point where some have insisted this film was a direct influence. As Carpenter was a film student at USC at the time the film was shown in Los Angeles, it's certainly possible that he might have seen it.

The story opens aboard the Dragon King-maru, a freighter and ramshackle passenger ship sacked by Japanese bandits, led by badly-burned, bald leader Tanuma (who looks like a slimmed-down Tor Johnson from The Beast of Yucca Flats). The sadistic pirates ruthlessly gun down everyone on board, including Dr. Nishizato (Ko Nishimura) and his new bride, Yoriko (Kikko Matsuoka). The bandits make off with 300 million yen in gold bullion while the ship is presumed lost at sea.

Three years later, Yoriko's identical twin sister, Saeko (also Matsuoka), is living with a Catholic priest (Masumi Okada) and dating seaside café owner Mochizuki (Yasunori Irikawa). Elsewhere, the Dragon King-maru returns to the Japanese coast, a ghost ship rolling in with the fog. Scuba diving, Mochizuki and Saeko encounter submerged skeletons chained at the ankles. They board the nearby ship, where Saeko encounters what appears to be the spirit of her dead sister.

Soon the ghostly Yoriko, aided by a colony of fluttering (and well-manipulated) rubber bats, begins her vengeance against the bandits. She compels one to the top of a lighthouse where he leaps to his death. In a particularly imaginative scene, one of the crooks, underwater in a diving suit, stumbles upon the half-dozen (wired together) skeletons. He panics, and when hoisted up by his shipmates is found dead, tangled in the netting with the vengeful skeletons.

Enthusiastically directed by Hiroshi Matsuno, The Living Skeleton has awesomely bad miniature effects (the Dragon King looking very much like a bathtub toy), while the unconvincing skeletons sport particularly unreal scowling skulls. The mad climax is certainly unexpected, resembling both Bela Lugosi's mad scientist cheapies for Monogram in the '40s and, more directly, Shintoho's similarly loopy The Woman Vampire (Onna Kyuketsuki, 1959). The only film of the four in stark black-and-white, The Living Skeleton even has the same overcooked contrast as those earlier Shintoho potboilers.

Also known as War of the Insects (a direct translation of its Japanese title), Genocide has a strong, even startling opening and climax, though it gets bogged down in routine espionage-in-the-jungle intrigue for much of its middle section. But in other ways the film is rather remarkable. One wonders, for instance, how Shochiku hoped to sell this angry, anti-American eco-thriller in the States. The U.S. military as depicted here are little more than hysterical, sanctimonious anticommunist thugs who'd unhesitatingly sacrifice all of Japan to radiated doom in the name of "freedom." And they're just one of this impressively nihilistic film's myriad targets.

In the Anan Archipelago, a fictional setting apparently patterned after Okinawa and other southernmost Japanese islands, married man Joji (Yusuke Kawazu) is carrying on a torrid affair with white woman Annabelle (Kathy Horan, in the role of her gaijin career), later described by one admirer as a "plump white butterfly." In the skies above, a B-52 is on a mission when it's inexplicably attacked by a swarm of insects, mostly bees. This somehow triggers flashbacks of combat in Vietnam for one of its crewman, drug-addicted Charly (Chico Roland), who goes nuts and, along with the bugs, causes the bomber to crash. Charly and two others parachute safely and take shelter in a cave where more insects attack. A bitten, sweaty, and hallucinating Charly is later found barely alive. (Throughout the film is squirmily uncomfortable macro-photography of insects biting real human flesh.)

Back in Tokyo, Dr. Yoshito Nagumo (Keisuke Sonoi) is increasingly alarmed by the toxicity of insects Joji has been collecting and shipping from Anan's Kojima Island. He decides to head down there to find out what's going on. Elsewhere, Japanese spies are working on behalf of a mysterious Eastern Bloc agent developing the insects for germ warfare purposes. Meanwhile, American soldiers, unaware of these fifth columnists, are themselves scrambling to implement "Operation Broken Arrow," to find the B-52's hydrogen bomb that was parachuted down along with the three men.

Genocide is all over the place, expressing outrage at U.S. and Soviet Cold War posturing, at the Vietnam war, Nazi concentration camps, nuclear weapons, the strained U.S. administration of Okinawa, mass murder, and environmental issues. There's a seedy interracial romance and a depiction of southern islanders teetering toward discrimination not uncommon then. (All the local men are sweaty, leering spies or promiscuous, cowardly layabouts.)

The picture has plot holes aplenty, like the conceit that the U.S. Air Force would knowingly allow a drug-addict soldier with post-traumatic stress and clearly on the deep end ride shotgun on a B-52. The set for the aircraft's cockpit and fuselage area, reused for the climax, is thoroughly unreal, closer in appearance to the multi-leveled futuristic aircraft seen in Toho's The Mysterians (1957) and Gorath (1962) than the realistic B-52 of Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove (1964).

The execution of other scenes borders on the unintentionally funny. When spies after the downed H-bomb find it in the jungle, with bees swarming all around, the first thing they do is point their guns in the direction of the bomb and shoot at the bees. Conversely, the supremely pessimistic ending has an undeniable power, and overall Genocide certainly doesn't deserve to be almost totally unknown, even among genre fans.

Despite the large cast of foreigners who often appeared in these kinds of films, including familiar faces like Harold S. Conway, Franz Gruber, and Mike Daneen, somewhat unusually all of their dialogue has been dubbed into Japanese rather than subtitled, which is perhaps another clue Shochiku knew they wouldn't have much luck selling this in North America and Europe.

Video & Audio

All four movies are presented in their original Shochiku GrandScope (2.35:1) format, with 16:9 widescreen enhancements. (The aspect ratios vary slightly, presumably to avoid negative splices, varying frame lines, and the like.) The transfers aren't great and most likely Eclipse/Criterion worked with the masters provided them by Shochiku. The film elements sourced are just so-so and, like Toho's video transfers (though curiously quite unlike DVDs and high-def transfers of Daiei, Toei, and Nikkatsu films) tend to be rather soft, though all are certainly far superior to what American audiences are used to expecting from Japanese fantasy films of this era. All have mono audio (Japanese only except for The X from Outer Space, which includes an alternate English-dubbed track) and good English subtitles.

Extra Features

Supplements are limited to Chuck Stephens's brief but good essays, a shame as much material exists in Japan (including a priceless trailer for The X from Outer Space) and audio commentary tracks (possibly including original cast members like Neal and Horan) would seem like naturals.

Parting Thoughts

At least two of these films are superior and far more original than your average monster spectacle and completely undeserving of their near total obscurity. The other two have moments of inspired lunacy and their long overdue release is most welcome. Highly Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is a Kyoto-based film historian whose work includes film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features. Visit Stuart's Cine Blogarama here.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||