| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

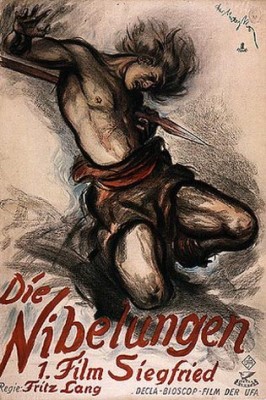

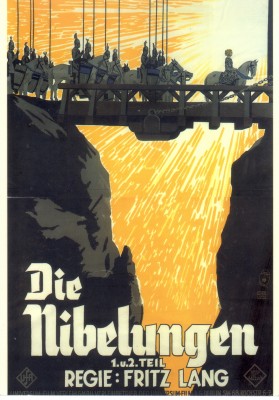

Die Nibelungen: Kino Classics Deluxe Remastered Edition

The Nibelungenlied is an epic German poem from the middle ages whose roots extend back into ancient Norse mythology, and in trying to explain the special quality and achievement of Die Nibelungen, Fritz Lang's epic, silent 1924 version of it, it helps to consider the story's original form and what it means to put it on the big screen in the way Lang has. To the extent that the coming of direct sound to the movies brought with it more of an emphasis on dialogue and "realism" and a de-emphasis of the purely visual, it allowed and encouraged post-silent cinema to try appearing more naturally dramatized, to have characters and situations that we come to know psychologically and verbally, and to maintain an illusion of cause-and-effect smoothness and real-life plausibility -- in other words, to be more "novelistic." Perhaps that's why the kind of pre-novel, oral-tradition literature represented by the Nibelungenlied -- which works in more boldly heightened, dazzling, and less "realistic" ways to spark the imagination and strike at the sort of deeper, timeless human truths and fears that can get diluted when filtered through the mundane-everyday constraints of naturalism -- has made for uninspired, easily forgotten movie versions since the talkies came along (like Uli Edel's attempt, for a recent example). But Richard Wagner proved the Nibelungenlied well suited to musical form in his most famous work, the 19th-century The Ring Cycle (which likely remains its most widely-known retelling), and Lang's gutsy move was to try doing for the cinema what Wagner did for opera. In Lang's hands, creating within the specific limitations and freedoms of silent cinema, it worked, and how: Die Nibelungen -- a sprawling, episodic, fearfully beautiful and accomplished film -- leaves one with the impression that the silent film, not the talkies with their temptation to parallel novelistic realism, was the visual medium most perfectly suited for the awe-inspiring, unfettered leaps of imagination contained within the more narratively crude but in some ways more profound (in the sense of being more primal, closer to the source) myths and legends from our deep, murky past.

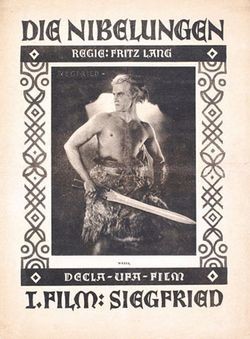

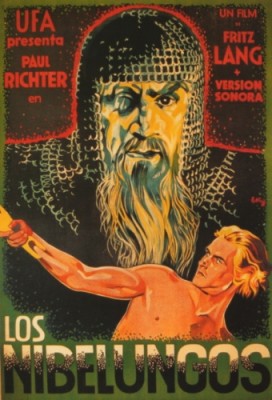

It took two full-length features -- Siegfried and Kriemhild's Revenge, released in succession in 1924 -- to cover the two parts of the legend, with all their convoluted plots, multiple characters, and magical digressions. In the first, the prince Siegfried (Paul Richter), who has apprenticed himself to a blacksmith in a primitive village in his homeland of Xanten, listens raptly as a bard tells of the faraway land of the Burgundians (whose people are also known as the Nibelung), where, in the city of Worms, the beautiful Kriemhild (Margarete Schon), sister of Gunther, King of the Nibelung (Theodor Loos), awaits. Spurred by this lovely vision (which Lang conjures onto the screen for our delectation, too), Siegfried sets off with the mighty sword he's fashioned, slaying a huge fire-breathing dragon along the way in one of the film's most memorably exciting sequences, then bathing in its blood (as instructed by a mystical bird) to render himself invincible...except, crucially, for the spot where a lime-tree leaf lands on his back, leaving him with a sort of Achilles heel of the spine. Before reaching Worms and Kriemhild, Siegfried also defeats a mercenary wizard-dwarf, winning a magical crown that can make him invisible, an even more powerful sword that should render him indestructible, and the "gold of the Nibelungen" that the wizard has spirited away and kept hidden. When Siegfried arrives at Worms, King Gunther and his close advisor and friend, the sinister one-eyed warrior Hagen Tronje (Hans Adalbert Schlettow), are reluctant to grant Siegfried Kriemhild's hand; the young prince then manages to win Kriemhild, earn Gunther's blood-brother friendship, and incur Hagen Tronje's ongoing suspicion and malice by using his invisibility and invincibility to make it appear as if Gunther is the athletic match of the imposing, imperiously amazonian queen of Iceland, Brunhild (Hanna Ralph), thus fulfilling her terms for becoming Gunther's bride. When it turns out that Gunther needs Siegfried's help with the alluring but demanding Brunhild in the bedroom, too, the deception becomes a festering secret that, when it reveals itself in a clash of rank between the two queens, leads to Brunhild's shaming of Gunther and her demand that he have Siegfried killed -- a condition that Hagen Tronje is only too happy to help the conflicted king fulfill after he pries the secret of Siegfried's weak spot out of the unsuspecting Kriemhild. With the sweetly trusting, now blissfully married Siegfried murdered by her brother's minions, and with the terminally bitter, imprisoned Brunhild taking her own life, Kriemhild, driven out of her mind with grief, vows revenge on her soul mate's murderer, no matter what or how long it takes.

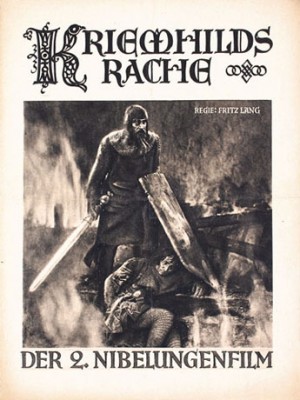

Which leads us from the intermittently sunny Siegfried (the pastoral beauty and rousing action of some of Siegfried's outdoor adventures meshes surprisingly well with the Expressionist artificiality of King Gunther's palace in Lang's and cinematographers' Carl Hoffmann, Gunther Rittau, and Walter Ruttmann's masterfully conceived and composed, frequently elating images, maybe because everything was shot in the studio) to the descent into darkness of which we're warned by the very title Kriemhild's Revenge; yes, Siegfried's widow's frozen-hearted vengeance is so extensive, thorough, and awful, it takes a whole additional feature-length part to completely recount. As Kriemhild later proclaims after her havoc has been wrought and everything, soon to include her own life, is extinguished, she died when Siegfried did. As her revenge unfolds, we can see that the Kriemhild of the first part has, indeed, passed away -- that the sweet, fair maiden of Siegfried has now without a doubt taken on a harrowingly dark aspect (wondrously enhanced by costumier Paul Gerd Guderian and makeup artist Otto Genath, who create a whole new quasi-gothic, covered-head, magisterially-mourning look to transform the wide-eyed girl into an ice queen) from which there's no earthly return. Kriemhild is courted, via an emissary called Rudiger (Rudolf Rittner), by Attila, King of the Huns, and though she will never love anyone but Siegfried, she consents to marry Attila on the condition that he and Rudiger take an oath to back up her vengeance upon anyone who's wronged her (she has someone specific in mind, of course). The film contrasts the Huns' squalorous primitivism with the graceful, stone-faced, deadly poise of their new queen, who will prove herself at least equally as "savage" as they. The loveless Kriemheld captures the heart of Attila and even follows through with bearing him a son in order to convince him that, once she's lured Gunther and Hagen Tronje to an ostensibly conciliatory feast, he and Rudiger (who has betrothed his daughter to one of Kriemhild's brothers, attaching him personally to the Nibelungen dynasty) must make good on their oaths and wreak her vengeance. When Attila's diplomacy restrains him and Rudiger is lost in battle, the now near-demonically driven Kriemhild incites the Hun rabble against the visiting Nibelungen, transforming a joint, orgiastic solstice celebration between the two peoples into a massacre; when even that fails, she sets fire to her own castle with her entire family trapped inside, finally killing the Hagen Tronje as he flees, in a murder-suicidal gesture (she knows she will be slain in her turn). This culmination of Kriemhild's massive vengeful destruction is horrendous and bone-chilling, but also tremendously, tragically moving: For her, it's a happy ending, because her death will finally reunite her with Siegfried.

Lang and his collaborator/wife, Thea von Harbou (the two also worked closely together on Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler and Metropolis) have no interest in making their Nibelungenleid's narrative tight or economical; it lurches at will, seeking out and mining the next seam of juicy action, swooning emotion, or petrifying, cruelly ironic fate. Its consequent episodic nature is blatant; doing justice to the epic-poem form it's taken from and fitting in well with the interrelated but separate installments of breathlessly forward-moving silent serials of the time, the film is divvied up into "cantos," reflecting its focus on building and channeling momentum without much regard to either smooth evenness of plot or what would come to be called "character development" -- again highlighting Die Nibelungen's closer resemblance to a poem or a musical structure than a novel. And this is a poem that reaches your heart through your eyes, making it sing before searing it with the monumental cruelty of the fate depicted: It's illustrious to say the least, and in a number of differently pleasurable ways. There's its sophisticated technical daring, which remains impressive almost 90 years later: the gigantic, studio-built, lifelike fire-breathing dragon; the superimpositions and trick photography that make Siegfried's invisibility eerily real; the astonishingly seamless turning to stone of the dwarves guarding the Nibelungen gold that, many decades before computerized "morphing" technology appeared; and even little forays into the avant-garde when Kriemhild's metaphorical dream of two dark birds attacking a white one* is brought to life via some truly lovely abstract animation, or when her mind's eye twists a blossom-laden tree into a skull as she foresees Siegfried's death. There's Lang's usual, subtle, cerebrally aesthetic brilliance: He fills the first part with compositions that depict characters climbing vertical structures (such as the giant, anachronistically pyramid-like staircase leading up to the Burgundian temple) and overhead shots with figures entering the frame from below and "ascending," most of which upward movement is noticeably absent from the darker second half; the Siegfried, with its ascents, heroic triumphs, and flowering of glorious love, is heaven, but the dark Kriemhild's Revenge would easily fit anyone's definition of hell. And, most immediately accessible and adrenaline-pumping, there's the fantastic choreography of the film's bountiful battle scenes, some featuring huge crowds of extras, that are so skillfully put together (through the conjoining of Lang's eye on set with his sense of tempo in the cutting room) that they still stand as a classic template for the well-made, clear, exciting, and dynamic action sequence.

Perhaps even more than it was for Wagner when he made his 15-hour Nibelungenlied opera, it's a forbidding, paradoxical challenge that Lang takes on, telling one of the most ancient and time-tested stories through the most new-fangled, technology-dependent medium of his time. But he acquits himself with splendor, proving that the big, ambitious idea of making a Nibelungenlied movie is one that he's more than capable of realizing with the colors and strokes available to him in the exciting, modern cinematic palette. The mise-en-scène of each scene -- whether teeming with action, stark to the point of abstraction as in many of the Burgundian-castle interiors, or stuffed with florid imagery or geometrical formations of extras to create rapturous pageantry -- is mesmerizing: the art direction and costumes are sometimes dizzyingly well-coordinated, playing off the sets and the actors' expansive silent-film movements in a way that alternately integrates the human figures with their surroundings and creates visual contrasts that make sparks fly, while the film's restorers have gone to great lengths to give us the most authentic experience possible by conscientiously including the film's original golden tinting (after years of incorrectly tinted or black-and-white versions) and a new performance of Metropolis composer Gottfried Huppertz's original, Wagner and Strauss-inspired score for the film (performed by live orchestras during its initial run) on the soundtrack. (It's worth nothing, too, that the film's set design was by Lang's future fellow expatriate to Hollywoodland, People on Sunday and Detour director Edward G. Ulmer.) Richter is very appealing as the youthfully handsome, strong Siegfried; Schlettow lends Hagen Tronje's die-hard villainousness a certain gravity; Loos uses his body language to effectively project despondence and wretchedness as the milquetoast King Gunther; and Rudolf Klein-Rogge is like a coiled spring as the terrorizing but besotted Attila the Hun. But this is really Schon's show, and you may have to watch the film twice to get your head around her transition from the sweet, fresh Kriemhild that falls in love with and marries Siegfried to the empress filled with a rage that consumes everything after he's taken from her. Lang straps us into the roller-coaster, reversal-filled destinies of these mythological characters and keeps us there through his own sublime skill at cinematic mythmaking, wringing all possible drama, excitement, terror, and elation from the story at every turn, and it's nothing short of thrilling. It's too-faint praise to claim thatDie Nibelungen is The Lord of the Rings of its time (J.R.R. Tolkien was apparently inspired by the Nibelungenlied, too), but that gives you some sense of all the scope, innovation, rousing razzle-dazzle, human emotion writ large, and cinematic virtuosity on proud display here. It's a huge, action-packed spectacle to rival those concocted by DeMille and Griffith, but with access to the bold, harsh, glacially-gleaming, tragically doomed finality of Northern-European myth. Once it's over, you'll be exhausted, emotionally drained, and already looking forward to the time you can put it back on and experience the whole intensely involving, transporting, and devastating dream/nightmare once more.

*That perhaps questionable dark-vs.-white metaphor brings up the potentially troubling Aryan-ness of the film, which is "dedicated to the German people" and does proffer tall, blond, alabaster heroes and some darker-skinned, animalistic "savages" in the form of the Huns. Die Nibelungen's standing vis-à-vis Nazi culture was ultimately redeemed, as was Lang's, but it is certainly a connection that announces itself and piques one's interest while watching. The matter is covered informatively and interestingly in the documentary supplement mentioned below; further insightful analysis can be found in Siegfried Kracauer's study of Nazism and German cinema, From Caligari to Hitler.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

A message appears before each part of Die Nibelungen, explaining in detail the restoration process, which involved the absence of an original negative and the combining together . That admirably honest disclosure/warning makes it easy to forgive the transfer's (AVC/MPEG4 encoded, 1080p mastered, at the original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.33:1) picture-quality inconsistencies or flaws, of which there aren't so very many after all. There is intermittent flicker and signs of print wear, occasionally very heavy, throughout; the most persistent issue is a small, one-frame row of black dots that appears at various places on the screen very regularly from start to finish (they look like tiny holes right in the celluloid, which would make sense given the conditions of the restoration). These are not nearly large enough in size to be an insurmountable obstruction to the film's impressive visuals, and even their frequency doesn't amount to enough of a distraction to mark this release's picture quality down when considering the rescue/restoration context. In the final analysis, one feels not only fortunate to be able to see Die Niebelungen (which could so easily have been lost forever) but confident, too, that the greatest possible care has been taken to give us the best-looking possible experience of it.

Sound:Both the DTS HD-Master Audio soundtrack and the PCM 2.0 mono track contain wonderfully clear, multilayered, and resonant sound, conveying a new performance (coordinated by Marco Jovic and Frank Strobel) of Gottfried Huppertz's original 1924 score composed for live orchestral accompaniment. (The DTS track, if you're set up for it, definitely does the better job of filling your viewing space and transporting you to a nice simulation of the live-orchestra-accompanied screening experience.)

Extras:--The Legacy of Die Nibelungen, a 68-minute documentary by Guido Altendorf and Ankle Wilkening. Made in conjunction with the Murnau Foundation's extensive restoration of the film, this supplement takes an amazingly in-depth and far-reaching look at its history, from the original production (complete with the narrator reading cast members' recollections, and with loads of footage, stills, and archived production memos onscreen for our perusal), to its complicated (but not quite as directly problematic as one might fear) relationship to Germany's rising ultra-nationalist right wing under Hitler, to the painstaking research and technical work done for the restoration, for which materials were gathered from far and wide and every decision was evidently made with sleepless-night conscientiousness. The Legacy of Die Nibelungen tells you pretty much anything you might want to know about the film in a direct, accessible, and even juicy way. The Die Nibelugen Blu-ray may not be packed with numerous supplements, but the inclusion of this excellent, thoroughgoing one is a good reminder that it's quality, not quantity, that counts.

--Two minutes or so of rare and valuable newsreel footage of Fritz Lang directing Die Nibelungen, including a staged gag in which he cuts a scene because a Hun extra is wearing a wristwatch.

--BD-ROM exclusive content (only playable on computers equipped with a BD-ROM drive) consisting of an essay by film scholar Jan-Christopher Horak.

A magnificent early reminder that the movies and the spectacular, mythological epic were made for each other, Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen is a sweeping retelling of a medieval German legend -- teeming with adventure, magic, shattered loyalties, vengeance, and ultimately tragedy -- that, adapted to film, is relentless in its sensational, heart-pounding beauty. Its two full-length parts are further divided into serial-like episodes, each one hurtling its way toward and into the next as our princely hero, the dragon-slaying Siegfried of Xanten (the statuesque Paul Richter) falls in love with a royal maiden from Burgundy, Kriemhild (Margarete Schon), only to lose his life through the jealousy and intrigue that lead to his brother-in-law King Gunther's murderous violation of their blood-brotherhood. But her husband's murder and her brother's broken blood oaths are taken with the utmost seriousness by the bereaved Kriemhild, who, destroyed by the death of Siegfried, spends the entire second film going literally to the ends of the earth (and far, far beyond reason and sanity) to avenge him, culminating in a volcanic, earth-scorching final scene of vengeance that puts Kriemhild in the leagues of Medea and Lady Macbeth as women unstoppable in their fevered pursuit of some instinctual, darkly implacable version of justice. In scene after scene, sequence after sequence -- from Siegfried's slaying of the dragon to his magical defeat of Brunhild, queen of Iceland, to his rapturous falling in love with Kriemhild, to Kriemhild's ominous dreams and the degeneration of her love for the murdered Siegfried into acts of pure, possessed vengefulness that include marrying Attila the Hun and inciting his wrath against her own people, resulting in orgies of destruction -- Lang gives us rousing action, replete with innovative and imaginative special effects that still impress, then tops himself with the fantastically ornate, intoxicating, orgiastically artificial aestheticism associated with the German Expressionist movement. Die Nibelungen's two parts, long as they are, are an ongoing, sometimes stately but nonstop upward spiral that continuously escalates the narrative and aesthetic stakes with long-shot, lavish battles and royal pageantry; swooning, close-up eroticism and anguish; and some terrifying, sheerly brutal violence of both deed and emotion. Lang's renowned instinct for the visually striking, along with the ravishing, high-budget excess that marks the silent, German period of his career, make Die Nibelungen soar ever higher, toward some cinematic heaven where the most basic human desire to see something intriguing, novel, action-packed, and sexy combines easily and elegantly with the deepest, darkest, most profound and foreboding depths delved by mythology. The film is at one and the same time lurid, restless spectacle; a worthy tribute to Northern-European oral-tradition legend more ancient and resonant than the written word; and boldly composed 20th-century art object -- one more testament, from Fritz Lang's singular body of work, to cinema's ability to absorb any other art, high or low, and offer us, in a sense, everything all at once. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||