| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

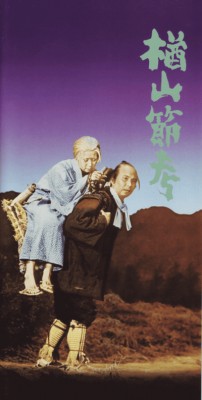

Ballad of Narayama (1958), The

Though acclaimed in Japan, where it was named Best Film by the influential Kinema Jumpo that year, The Ballad of Narayama also reflects its era technologically and in terms of the international marketplace. Japanese movies began receiving worldwide attention in the early 1950s and the Japanese began tailoring many of their biggest, most prestigious productions with the western market in mind, a market that seemed to favor only Kabuki and Noh-flavored period films.

At the same time, Japan was making its first color and widescreen movies (Kinoshita's Carmen Comes Home was, in fact, the first color feature), with Japanese cinematographers' use of color particularly impressing western audiences. The Ballad of Narayama was photographed in Fujicolor and Shochiku GrandScope, an anamorphic widescreen process nearly identical to CinemaScope.

Criterion's 2K digital master utilizes a 2011 restoration by Shochiku and Imagica. It's not perfect but these imperfections may be more the result of the early Promina lenses being used rather than the transfer itself. Extras are light but include a nice booklet and two trailers, one of which has footage of Kinoshita on the set.

Set roughly in the early 19th century in rural, northern Japan, The Ballad of Narayama deals with the tradition of ubasuteyama, in which (usually) elderly parents are carried into the mountains by their children and left there to die of starvation or exposure, so that the younger and stronger generations have a better chance to survive the endless droughts, famines, and particularly harsh winters. Not only did this practice really exist, cases of ubasuteyama were still being reported in Japan's poorest rural areas even after World War II. Furthermore, wandering into Japan's thickest forests and mountains and getting lost is still a popular if discouraged form of suicide.

The story concerns one such village where the elderly are carried off to their doom upon reaching the age of 70. Matriarch Orin (Kinuyo Tanaka) is 69 when the story begins and in exceptionally good health. (The great actress appears to have padded her back slightly, realistically suggesting scoliosis.) But she's already resigned to her fate, even eager to see it carried out. Partly this is because the pilgrimage has a religious significance, a chance to meet the Mountain God and be reunited with lost loved ones. There's also the matter of family pride; her willingness to face death with courage and honor will benefit her family's standing in the village. However, Orin's 45-year-old widower son, Tatsuhei (Teiji Takahashi) is in a kind of denial a long way from being reconciled to the inevitable.

Conversely, Tatsuhei's selfish, pushy, and brazenly insensitive teenage son, Kesakichi (Kabuki actor Danko Ichikawa [III], later known as Ennosuke Ichikawa III), can't wait for her to make that trek up the mountain. He has a piggish, equally insensitive pregnant girlfriend, Matsu (Keiko Ogasawara), and there'll be more food for them once Granny's out of the way. Even though Orin is determined to leave the family when her time is up, if not sooner, Kesa-kun taunts her mercilessly with a song mocking the fact that she still has all her teeth. Soon the entire village is singing the boy's cruel song.

Shamed by her own good health, Orin succumbs to pressure and deliberately bashes her perfectly healthy front teeth against a grindstone, shocking everyone at a nearby Obon festival, bloody-mouthed and smiling with toothless pride.

But Orin does manage to secure her son a new wife, Tama (Yuko Mochizuki), a gentle woman shocked by Kesakichi's and Matsu's abhorrent behavior, and who recognizes Orin's incredible strength. Contrasting this is a subplot concerning another old but pathetic villager, 70-year-old Mata (Seiji Miyaguchi, barely recognizable as the master swordsman in Seven Samurai four years earlier), who refuses to go quietly despite constant abuse from his barbaric adult son (Yunosuke Ito).

The Ballad of Narayama borrows certain theatrical iconography from Kabuki, though the performances, makeup, and dress don't emulate Kabuki at all. Still, the film opens with the banging of ki wooden clappers by a joruri narrator, as in Kabuki, with the announcement of the film in front of a traditional striped curtain, or joshiki maku, which opens directly into the story in the manner more recently co-opted by Wes Anderson.

Except for two very effective shots at the very end, the entire film was photographed indoors, on vast soundstage sets with painted skies and forced-perspective landscapes incorporating miniature huts and mountains in the background. Shooting everything under such controlled conditions facilitated all manner of lighting and staging effects. Within certain scenes the lighting switches from naturalistic to highly stylized, bathing the set in reds and greens particularly. Late in the film there's a magnificent bit of staging involving the sudden appearance of black crows that would have been hard to achieve on location; the fact that one of the crows disappears behind a "mountain" the size of a pillow doesn't diminish its effectiveness.

The reason for all this theatricality isn't entirely clear, but perhaps partly its deliberate artificialness is intended to offset the truly horrifying aspects of the story, material more disturbing than most horror movies.

Even faced with starvation, the idea of abandoning elderly parents in the mountains is an excruciatingly difficult concept for western audiences to absorb. But in Japan, where the needs of the individual always comes last, where failing health and death are accepted as a part of life, and where self-sacrifice is considered honorable and sometimes obligatory, The Ballad of Narayama is less alien.

But what exactly is it the material is trying to impart? Are Orin's actions, particularly in terms of wanting to secure her son's future, worthy of praise or merely tragically wrong-headed? Is Mata, in resisting the inevitable, being selfish?* In Philip Kemp's excellent booklet essay, he suggests a link between the sacrifices of the individual here to wartime militarism but I disagree. Indeed, Orin is a lot like the selfless mothers whom dutifully and without tears sent their sons off to war in Japan's wartime propaganda films.

Video & Audio

Helpful liner notes explain that The Ballad of Narayama's original camera negative was too damaged to be scanned directly, and so the transfer sources a interpositive, wetgate-printed from the OCN and scanned at 4K. Fujicolor elicits a subtly different range of hues compared to Eastman Color stock, yet the transfer thankfully doesn't attempt to conform to that more familiar look. The image is a little soft at times though it's hard to tell if this is due to the anamorphic lenses or that combined with the limitations of the IP. The results, particularly the color, are still impressive; the best high-def transfers I've seen of Japanese color/'scope films of the 1950s appear only marginally better. The mono audio, Japanese only, was remastered at 24 bit and the English subtitles are new. The disc is Region A encoded.

Extra Features

Supplements are limited to a teaser and a trailer, and as noted above one of these features a couple of brief behind-the-scenes shots, not uncommon in Japanese trailers of big 1950s and '60s productions. They are spoiler-filled, however, so be sure to watch them after the film.

Parting Thoughts

An important if not exactly representative work of director Kinoshita, The Ballad of Narayama is still very impressive in its experimentation and for Kinuyo Tanaka's performance, while the story is still harrowingly effective even all these decades later. A DVD Talk Collector Series title.

* Reader Sergei Hasenecz opines, "I do not think Orin's self-sacrifice necessarily needs to be seen within the context of her time and place in order to be viewed as a noble act, if ultimately one of beau geste. She is mocked by a member of her own family, as well as her village, all of them selfish and ungrateful. Yet she sees her sacrifice as part of their survival, as well as for her to be rewarded with religious fulfillment (she will meet the mountain god and be reunited with family who have gone before). Her son is reluctant for her to take this deadly course, but her determination includes her own self-mutilation (knocking out her teeth) ... How hard is all of this to translate to Western audiences? Not hard at all. Think of how many good Christians would be falling to their knees if this was the story of a Christian martyr. Orin would probably have achieved sainthood and her story retold in sermons and Sunday school: sacrifice of self for the greater good and the chance to look God in the face. By Western standards, she is a Christ-like figure ... Is Mata being selfish? No. He doesn't want to die, and who can blame him? I think in the same situation most people would be like Mata rather than Orin."

Stuart Galbraith IV is a Kyoto-based film historian whose work includes film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features. Visit Stuart's Cine Blogarama here.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||