| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

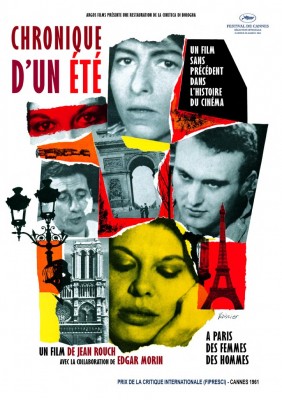

Chronicle of a Summer: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional and other sources, not the Blu-ray edition of the film under review.

We're all fairly well-accustomed by now to movies that openly, self-reflexively acknowledge their own artificiality -- so many different filmmakers, from Godard to De Palma to Tarantino, have been doing it for so long, each for their own purposes ranging from post-modern playfulness to agonized intellectual frustration -- but the ethnographic/anthropological documentaries of Jean Rouch were among the very first to make this bold move, scrutinizing themselves up there on the screen, right before our eyes. Rouch's 1960 collaboration with sociologist Edgar Morin, Chronicle of a Summer (Chronique d'un été) is a prime case in point, and one that that hit unusually close to home for him. Rouch, a Frenchman, was best known for making field-studies in Africa, where he would film the daily lives and customs of Africans, then screen what he'd shot and put together for his subjects, allowing them to comment on the images he'd made from their lives -- a dimension that would then be added in to the film as its own built-in criticism and acknowledgment of the gaps, oversights, falsities, and failings that unavoidably occur when any filmmaker, whether working in fiction or nonfiction, makes his or her shooting/editing choices. But in this film, made during one of his rare sojourns back home to France, he focuses his curious, rigorous camera eye on a group of Parisians of various classes and origins, teaming up with his academic colleague Morin to ask a seemingly simple survey question -- "Are you happy?" -- of people on the street. But, of course, it's not at all simple; the question itself, along with the act of posing it with a microphone and a camera, opens up a Pandora's box of social, political, and artistic complications that, as the film itself acknowledges, can neither be put back in nor in any way resolved in an hour and a half of screen time.

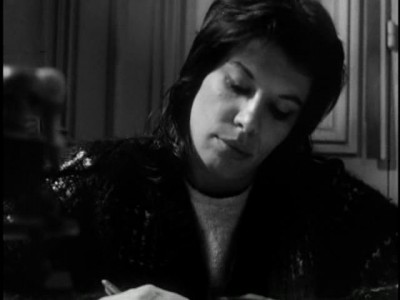

That doesn't mean, however, that Chronicle of a Summer lacks for clear-cut, sometimes genuinely revelatory appeals to our innate human fascination for how other people feel, think, and live, or for a structure that juxtaposes the intended work with the rather different thing that actually got made, in a way that's never so chaotic that we can't properly grasp it and mull it over. The filmmakers themselves appear on camera, of course; one of the first things we see is Rouch and Morin explaining to their trainee representatives out on the street, Marceline and Nadine, how to use the then very technologically advanced Nagra direct-sound tape-recording packs and microphones as they interview strangers for the camera -- our first "behind-the-scenes" hint of what the directors intend to be the film's full disclosure, a refusal to hide its tools or mechanisms from us, the viewers. There's then a flurry of predictably fruitless responses from random Parisians to the question, from total disdainful avoidance to camera-hogging rambling; a net cast this wide is clearly going to let everything slip through and come up with nothing of substance, never offering up the hoped-for details and characterizations of what people's lives are like in contemporary France. (French New Wave king Jean-Luc Godard frequently venerated Rouch as and direct influence, and large swathes of Godard's 1965 film Masculin-féminin work a reiteration of this exact same public-survey-taking conundrum into its own vérité-style sociological drama.) So Rouch and Morin, in what we glimpse playing out as heated acts of re-thinking on their feet and harried decision-making, lose the overly-general breadth and go narrower and deeper, selecting a small handful of their random interview subjects and people they were already acquainted with from their own circle -- a Renault factory worker named Angelo; a couple of students called Jean-Pierre and Régis; a former political comrade of the communist Morin's who's now said goodbye to all that for a white-collar bourgeois life; a student from Africa, Landry, who had once been; and a severely disillusioned young woman, Mary Lou, a Cahiers du cinéma secretary who's come to Paris from Italy and had her romantic dreams of a more meaningful life dashed -- along with people directly involved with their project (the aforementioned interviewer Marceline becomes one of, if not the, central character in the film) to talk about their lives, their experiences, as well as about the process of making the film and what, if any, value or authenticity might be attained under the innately false conditions of camera and sound recording. Morin, with Rouch's reluctant acceptance, gathers these quite disparate subjects together for dinners held in front of the camera, where he hopes that the clash of very different personalities, communication styles, and walks of life will throw off sparks that might illuminate the ways these people are living, why, and what that means to them.

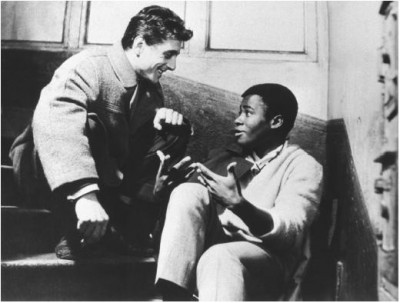

What comes of these more circumscribed, limited efforts might at first seem merely topical, or too personal/subjective to be of much use in creating the snapshot of Society that the filmmakers had (naively, it more and more seems as the film plays out) initially wanted Chronicle of a Summer to be. The headlines of the day are anti-colonialist resistance in Europe's African colonies -- violence against Belgians in the Congo by their oppressed "subjects," and also, of course, the ongoing reactionary war waged by France to suppress independence-seeking Algeria, a military engagement about which every person on camera has very strong feelings, and which affects the young male students in particular in a very deep way, as their obligatory military service looms to draw them into the role of oppressor, whether they agree or not. Landry is introduced to Angelo by Morin for a staged but fruitful exchange in which the African-immigrant student and the world-weary laborer strike up a sort of friendship (even if explicitly preconceived and staged as a sort of cross-cultural gesture by the well-intentioned Morin) as they compare and contrast their experiences as an African living in France and an unfulfilled member of the French underclass. (Angelo also gets into it in a more spontaneous, less friendly way with a sound technician who's taken risks to live the dream of working in the cinema and is more than faintly dismissive/disdainful of the plight of manual workers like Angelo, who can't or won't take such risks to find a job that, like his, offers more independence and fulfillment.) Rouch, in his turn, provokes Landry and some of his fellow African students, when they're discussing their sometimes irksome and painful experiences of being black visitors to France from its African colonies, by asking them if they know what the number tattooed on Marceline's forearm means, if they know what the concentration camps are (they do; they've seen Night and Fog) -- which then, after a benevolent but awkward moment of explanation, segues into one of the film's most intimate sequences, in which Marceline walks down the Place de la Concorde, musing on the contemporaneous public trial, in Israel, of the Nazi criminal Eichmann (another headline of the day) while revealing her traumatic memories of being at Auschwitz and undergoing the dehumanizing "selection" process that separated the Holocaust's murder victims from those Jews that would be allowed to live for a while longer. (This scene also may be the finest visual moment in a film whose handheld black-and-white photography, "raw" but lyrical in a way that puts it right in keeping with the concurrently exploding French New Wave of movies, is always inventive and frequently beautiful; among the group of highly skilled cinematographers was the New Wave cameraman-icon, and Jean-Luc Godard's go-to DP, Raoul Coutard.)

However, contained within and shining out through these pervasive time-capsule references to issues whose powerful currents were at that time intersecting with and seeping in to preoccupy the increasingly troubled, doubtful, or angry minds of the people who are being filmed, there's a much deeper, more timeless sense in which we are glimpsing something like the realization of the ambitious project Rouch and Morin had envisaged, which seems more and more impossible as the film progresses. Not just the "characters'" opinions (which are, after all, of no small interest in and of themselves), but also details of their personalities too idiosyncratic and caught by surprise to be faked; spontaneous unmaskings of prejudices; and an occasionally very authentic (if fleeting) fixing-in-place of the feel, texture, reasoning, experience of their lives, are simultaneously complementing and/or jostling against one another during all those filmed conversations in which the subjects' differences and the contentious issues of the day have been purposely brought up as not only sure conversation-stokers, but as a catalyst to see what they might disclose (or hide, or give short shrift to) about themselves, their feelings, and their lives. We also, crucially, see each of these mostly young (or, at latest, approaching middle-aged) people in some kind of spontaneous situation or action at least once, most notably during a scene in which they partake of the French tradition of fleeing Paris in August, in their case for a sojourn to St. Tropez, where they continue to ponder their sociological questions (a monologue from a young woman who works as a sexy summertime model, posing for photos with male tourists, is surprisingly reflective and incisive, with the filmmakers' (and our?) prejudiced surprise, not the young lady's combination of brains and beauty, being the revelation), but where, more importantly, their play -- dancing, swimming, sunbathing, rock climbing, etc. -- gives us a facet more visible than verbal, rounding out and humanizing them in a way words can never quite arrive at accomplishing.

And perhaps the primary thing of value that Chronicle of a Summer's invigorating, highly engaging investigation ultimately unearths over its meandering, sometimes floundering, consistently second-guessing and self-correcting, never less than intriguing and entertaining course, is a sobered but not entirely defeated recognition that isolating this or that facet of a person's experience, brief snatches of Real Life -- possibly combining them in interesting or suggestive ways, but never being able arrive at the complete picture -- is as close as a documentary film can get to really conveying the truth(s) of people's lives in their specific culture(s), society(ies), and epoch. Rouch and Morin's perpetually conscience-stricken, almost masochistically honest approach reveals in decisive terms the difference between "direct" cinema (e.g., the Maysles' Salesman), where the filmmakers efface themselves so that it appears that we're watching real life unfold in an unmediated way, and the cinema vérité they were in the process of inventing and defining, where the "truth" of what we're seeing can only ever be conditional, and must include, if the film can have a claim to any truth at all, an acknowledgment of itself as as a film -- as a contrivance, however noble, inescapably burdened with artifice. We take our leave of the film's various on-camera participants, whose realities Rouch and Morin have tried (with limited, if any, success) to convey, as the lights come up on them in a screening room after they've witnessed themselves in some of the footage the filmmakers have selected and put together. They equivocate about the film, complimenting but more often criticizing what they've seen; some attack the film, some attack their fellow subjects, some defend themselves, but on the whole, the doubts and displeasure far outweigh any approval.

Then, in conclusion, it's Rouch's and Morin's turn to submit to their own camera for a brutally honest assessment: They amiably, if somewhat disconsolately, recap their own disagreements about the project while strolling through their own natural habitat, Paris's Museum of Man, attempting to separate the wheat of authentic, meaningful moments and dialogues in the film from it chaff -- the bits where the presence of the camera drew what they consider false, exaggerated, or otherwise altered "performances" from their "real" subjects. They part on the sidewalk outside; "We're in it now" is Morin's final, terse, ambiguous word to Rouch as they head in different directions to blend (back) into the anonymous flow of Parisian life. Their film has failed to attain the holy grail of "closure," to close the book and leave us with any definitive knowledge. Why, then, is it so inspiring, compelling, and intensely watchable, despite its aura of self-doubt and inconclusiveness? Perhaps because opening a book is just as laudatory a goal, and because Chronicle of a Summer is a film whose rare, open, agonized commitment to its own integrity practically demands that it be inconclusive if it has any hope of being of any worth. It is, in fact, a movie of great worth after all, on different terms than the filmmakers originally conceived -- a confused and chaotic journey, but one that very effectively implicates the viewer, too, reminding us of how slippery objectivity is, how we're all "in it," stuck with one form or another of subjectivity and unspoken, baseless assumptions; how none of us, whether through a camera or our own eyes, observe or experience our world from some olympian height; and how we might be well-advised, if we mean to ever understand each other in any meaningful way, to always keep that condition humbly in mind.

Video:

Chronicle of a Summer's transfer (AVC/MPEG-4, 1080/24p, at the original aspect ratio of 1.37:1) is a very good-looking, faithful restoration of Rouch and Morin's images, made by the Cineteca di Bologna from a brand-new 2K digital master. It looks as sharp and clear as would be authentic (this is an on-the-street documentary shot on a patchwork of 16 mm and 35 mm film under varying conditions), with virtually no compression artifacts or edge enhancement, but without doing an overzealous scrub-job with digital noise reduction (DNR) or sacrificing any more of the film's natural grain than absolutely necessary.

Sound:The uncompressed PCM monaural soundtrack is also an excellent, best-of-both-worlds restoration job, with all natural clarity, sharpness, and fullness of the film's direct-recorded sound (mostly dialogue, but also with plenty of ambient/street sound and the like in the background) preserved, but without going out of bounds to artificially modernize, spruce up, or amplify anything, so that the sound retains a texture that feels right for the images it's accompanying, which we're better able to judge than we usually are because those images actually show us how the film's sound was made.

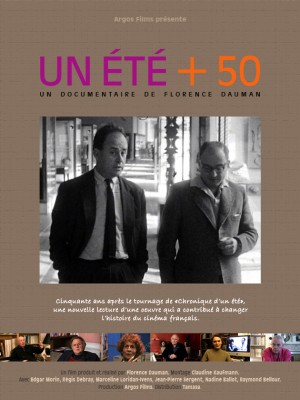

--Un Été + 50 (73 min.), a 2011 documentary by Florence Dauman (daughter of Chronicle of a Summer's producer, Anatole Dauman). In addition to bringing in French ciné-intellectual Raymond Bellour to comment upon the film's significance, Dauman catches up in the present day with Morin (still alive in his 80s, unlike his colleague Rouch, who passed in 2004) and some of the film's subjects (the most prominent among whom is Marceline Loridan, but also including Jean-Pierre Sergent and Régis Debray, among others), who look back with a mixture of bemusement and affection at their experiment from decades ago. The film makes for an excellent addendum to the original Chronicle of a Summer; Morin explicitly places his and Rouch's work -- both the act of making it and the rest of what it depicts, and how -- on a timeline of skeptical, critical thought and action leading toward the French student/worker revolts of 1968, and it brings to light some of the political discussion (unearthed and shown within the film, along with a generous handful of other deleted scenes) that had to be cut from Chronicle of a Summer in 1961 to avoid censorship. The scenes in question brought in the issue, extremely contentious in French society at the time, of French colonization of/military presence in Algeria; the ongoing anticolonialist Algerian revolt against the French government; and France's violent military suppression -- a topic so controversial that Pontecorvo's Battle of Algiers was banned in France for years after its 1966 release, which would seem to prove Rouch and Morin correct about the fate of their film if it heated Algerian-war discussions had been left in.

--A 1962 television interview with co-director Jean Rouch (5-1/2 min.), in which the ever-principled Rouch honestly explains the differences between Chronicle of a Summer and his earlier films made in Africa, and shares his thoughts on his latest film's relationship to the concurrent French New Wave, about which he is moderately enthusiastic, if ambivalent. (His predictions on the cinema's splitting into "entertainment" films "like The Folies Bergeres" and the kind of "experimental/avant-garde " films he's interested in, with the latter claiming a smaller share of the audience and perhaps even consigning themselves to TV, are remarkably prescient.)

--An interview with Marceline Loridan from the 1961 Cannes Film Festival, where Chronicle of a Summer was screened. Loridan talks with smiling modesty to a rather blunt interviewer (whom we don't see) about whether opening up about her experience in Auschwitz for Rouch and Morin's camera was "exhibitionistic,"; is asked about her personal feelings on the then-current death-penalty trial of high-up Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Israel; and concludes by rejecting the luxury and "high society" she's experiencing at Cannes as "cut off from reality."

--A contemporary interview with anthropology professor Faye Ginsburg, a onetime colleague (for a brief period in the late '70s) of Rouch's and evidently something of an expert on him, his work, and the making of Chronicle of a Summer. Ginsburg she goes into some fascinating and illuminating detail about how the film came to be and the way it was made, touching on the very different, even contradictory, approaches of the more action-oriented Rouch and the more dialogue/psychoanalysis-dedicated Morin, and the fruitful tension that caused. In addition, for cinéphiles (at least for this cinéphile) her explanation of how "cinéma vérité" (a documentary film that hopes to arrive at a complex truth, including that of its own making, and so will acknowledge the filmmakers' presence explicitly, onscreen, in the film itself), despite having come into use as a synonym, differs markedly from "direct cinema" (the fly-on-the-wall, strictly observational, "objective" type of documentary in which subjects are discouraged from acknowledging the camera) is of particular interest and usefulness.

--A well-designed and -illustrated (this is The Criterion Collection, after all) 35-page booklet featuring an in-depth essay on the film by film scholar/professor Sam Di Iorio.

The uniqueness of Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin's 1961 documentary Chronicle of a Summer is still striking after all these years; it inspired a wave of self-consciousness and self-interrogation that continues to ripple through movies and inspire both fiction and documentary filmmakers, but its own particular self-awareness, perhaps what Rouch and Morin were up to represented such a risk and a novelty at the time, still feels fresh, inimitable. At the outset, the film presumes to survey random interviewees from the Paris streets during the summer of 1960 to answer the question "Are you happy?" and thus ostensibly form a revealing composite portrait of what French social reality is like as experienced by individual citizens. But that tactic quickly stumbles, and the film becomes basically an incisive self-examination, a sometimes self-lacerating recounting of its own missed-target attempt at something more definitive than it is (or could be), morphing before our eyes into the chronicle a (summertime) sociological/anthropological experiment gone awry and struggling to find itself -- its proper methods, its real goal -- along the way, stopped constantly in its tracks by the refusal of teeming, arbitrary, unpredictable Life to conform to even the most intelligent and probing standards conceived in an ivory tower. To the credit of Rouch and Morin, however, the film is saved in at least one sense (becoming something greater, more interesting, more fruitful than they could have planned it to be), in that at least one component -- and it turns out to be the most significant dimension, the one in which they succeed beautifully, if in a completely unexpected and counterintuitive way -- of their project is bringing their disciplines down out of that ivory tower to engage with (or at least conflict and contrast productively with) life on the street, to break the academic vs. workaday life stalemate, even if it comes to light in the process that their most innovative methods can't answer their important questions about human life and happiness in any very satisfactory way (and even if serious doubts are raised along the way as to whether such questions can ever be answered in a manner both rigorous/systemic and convincing). If ever gold was spun out of a project doomed to failure by its own unrealizable ambition, elevating itself to a different kind of achievement through its own willingness to dig into and examine that failure, to discard unworkable assumptions midway and ask new questions, that alchemy has come to pass here for Rouch and Morin. Chronicle of a Summer rises from its own ashes to become a picture that doesn't lose, but actually enhances, its thought-provoking power by being as much about itself as it is about its subjects. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||