| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

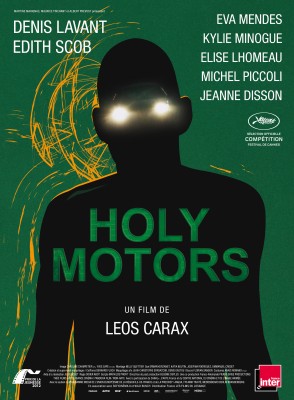

Holy Motors

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials provided by the film's distributor, not the Blu-ray edition of the film under review.

It's an epiphany that will come at different points for different viewers of Léos Carax's Holy Motors -- that moment amid the film's mysterious, increasingly bizarre plot(s) when you realize that what it's "about," in the largest sense (not that you can entirely pin it down or reduce it), is what the incurably cinephilic Carax evidently regards as the mechanical, certainly, but also the sacred spirit of the medium itself, right now, in a transitional moment of simultaneous elation and crisis as it undergoes radically shifting production and distribution models and technologies. Few filmmakers are better suited, by temperament or experience, to spin such an ambitious, free cinematic allegory about the nature and evolution of the cinema: Even at the hyped-up beginning of his career, when longevity didn't necessarily seem guaranteed as he created a splash with such cinema-history-saturated, playful/postmodern-y films as Boy Meets Girl and Bad Blood (Mauvais sang), Carax was easily the most well-regarded of a slightly dubious '80s school of French cinema that, flirting dangerously with the tricks of advertising and music video, came to be known as le cinéma du "look"; scholars Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, in their encyclopedic textbook Film History, singled out Carax as the "most resourceful" of these Parisian trendies, and Holy Motors vindicates that assertion and then some. It's the ultimate proof that he's far and away the most durably talented of that probably too-conveniently lumped-together group (which also included Betty Blue director Jacques Beineix and the eternally slick Fifth Element auteur Luc Besson, neither of whose work has come close to being either as ambitious or as accomplished as Carax's). In Carax's own body of work, Holy Motors is at least as significant an advancement/expansion on what he's done to date as his last big artistic leap forward, 1991's The Lovers on the Bridge. With this new masterpiece -- an eye-popping and mind-blowing realization of brazenly large, epochal ambitions that sweeps you entirely off your feet to envelop you in its heady rush -- he's unexpectedly catapulted himself into the uppermost echelon of contemporary filmmakers.

The film does offer, from the beginning, mounting clues as to how far-reaching its contemplation of the seventh art will be. After opening credits that suggestively feature snippets of the earliest silent/black-and-white movie experiments (their novelty deriving exclusively from the 19th-century miracle of photographs of human figures actually coming to life, but their beauty and intrigue somehow still remaining), we're witness to Carax himself as a sort of Alice figure, following (and, in his turn, leading us) down a rabbit hole, awakened by the incongruous sound of a foghorn in the middle of the night in his anonymous suburban-Parisian flat. Our director is only mildly surprised, if at all, to find that he's equipped with a metal finger that will open the lock hidden amid the dark forest depicted on one wall by eerily life-like wallpaper. This portal leads him to where the foghorn sound is coming from, what we've already briefly seen in a preceding image: a huge cinema auditorium packed to capacity with viewers whose faces are too shadowy to discern their features, watching a film whose mysterious sounds (violent shouts and murderous gunfire, that foghorn -- departing, concluding sounds) contradict the infancy-of-cinema clips we've seen. Carax's eyes willingly join theirs, and ours, in the transfixed spectatorship of what follows, and we cut once and for all to the movie screen inside the movie screen to witness what plays out over the next 90 minutes, which will thematically encompass all that the motion picture has been until now, from its birth in the past to its impending death/departure for unknown territories: A day in the life of the film's principal personage, M. Oscar (Denis Lavant, whom Carax discovered in the '80s as his unlikely but intensely gifted leading man, and whose career has since encompassed many different shades of brilliance in projects as varied as Claire Denis's Beau travail and Harmony Korine's Mister Lonely, in which he quite aptly played an ersatz Charlie Chaplin). This middle-aged family man leaving for work appears at first to be a fairly anonymous, discreetly besuited upper-crust business type as he departs his expensively unique suburban home, whisked away in a subtle white limo by his driver, Céline (Édith Scob, whose long-ago, legend-making star turn in Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face (1960) is eventually proved to have a surprisingly deep significance, well beyond a trivial reference, in the cinephilic context Carax is creating). Céline is both driver and secretary; she informs M. Oscar that he has nine "appointments" today.

These rendez-vous, however, are anything but usual business. Each one turns out to be a kind of mini-movie, a transformation of a "real-life" situation in which M. Oscar plays some fundamental role that blurs and blends reality and fiction: He has a lighted mirror and a makeup kit in his limo/dressing room that he expertly employs to age, regress, or otherwise transmogrify into virtually any face and shape. But his first role, that of a hump-backed gypsy woman begging on a bridge, doesn't make what M. Oscar does for a vocation quite clear just yet. We infer it gradually, over his subsequent transformations, each demarcated with an interval inside the limo to allow for stepping out of the old and into each new character -- as well as from his ongoing discussions with Céline and a surprise, portentous visit from his boss at "the agency" (Michel Piccoli, star of scads of great French films from Contempt to La Belle noiseuse to Carax's own Mauvais sang, rendering him the male ghost-of-cinema-past equivalent to Scob's grande dame): M. Oscar is the roving emissary, one among many (the other one we get to meet, in a moment of unexpected interaction with Oscar that turns into a tender, soaring riff on movie musicals, is played beautifully by pop singer Kylie Minogue, performing an unforgettably melancholy tune -- live on camera! -- written for the film by English songsmith Neil Hannon) employed by none other than the dream factory of cinema, an outfit that is revealed, at the end of Carax's brilliant allegory, to go by a peculiarly appropriate brand name, "holy motors."

The film's form -- its look(s), its style, its very mode of production -- follows its function, with Carax's director of photography, the supremely gifted Caroline Champetier (Of Gods and Men, Anne-Marie Miéville's The Book of Mary) reflecting the film's concurrent, multidimensional obsessions with cinema past, present, and future by using a particularly of-the-moment camera, the RED Epic, that's been embraced by a multiple adventurous filmmakers for offering a "film-like" look at the same time as it's fully, economically digital, the most advanced non-celluloid technology available. Thus, both machine ("motor") of the technology used and the "holy" creative inspiration of the conceptual and performing artists at work are in philosophical tandem as they cast their enraptured glances backward and forward in time, all while remaining dynamically in the present. Carax, Champetier, and the incredibly versatile Lavant create masterful simulations of scenes/sequences idiosyncratically chosen and re-imagined from across the depth and breadth of film history: In addition to the aforementioned gypsy-beggar and musical "appointments" that M. Oscar must attend to, there is a scene that has our hero-who-contains-multitudes dropping in to a high-tech compound/special-effects chamber to perform, with hypnotically ritualistic precision, a series of motion-capture maneuvers (the future of cinema? as shot and choreographed here, it does have a distinctive, celebratory visual beauty to it) before a female co-actor joins him to create, again through their captured motions, a sort of abstract, otherworldly/underwater soft-core production (a hyper-futuristic computer-generated movie revealed, in a lovely paradox, through nothing more than an old-fashioned pan from the actors doing their motion-capture thing to a big screen displaying the technologically-mediated result). There are assassinations both highly aestheticized (M. Oscar embodies a gangster ceremoniously murdering an enemy, also played by M. Oscar, for a delirious mirror-effect) and righteously enraged (a shirtless, sloganeering revolutionary-warrior M. Oscar guns down the "banker" he himself was playing at the film's opening). Carax adroitly immerses us in more familiar/naturalistic dramatic exchanges, more subtle but done with no less skill and passion, involving a psychologically character-revealing exchange between a father played by M. Oscar and a teenaged daughter, like something out of one of Olivier Assayas's incisive domestic dramas; elsewhere, we're caught up midway in the excruciated, Michael Haneke-like stark stillness in which the final moments playing out between a dying elderly man (M. Oscar once more, of course) and his beloved niece.

In what is perhaps the film's most striking, enigmatic episode, Carax has M. Oscar revisit a repulsive, half-animal, satyr-like character -- a troll from the sewer named in the credits as "Merde" -- that he and Lavant created for their contribution to the omnibus film Tokyo!. Here, this strange, pre-verbal, obscenely vaudevillian, only vaguely human-esque creature rises up from beneath the city to emerge in a cemetery, an entrance that plays out in a jittery/irising-in silent-movie pastiche as he chows down voraciously on stray bouquets left by mourners, before the plot itself flowers intoxicatingly into a monster movie with shades of both King Kong and Beauty and the Beast, this unwashed, gnarled, generally repulsive troll with years' worth of fingernail growth intruding upon a fashion shoot that's been set up in a gated corner of the cemetery (to the delight of the tackily "postmodern" hipster photographer, who gleefully proclaims the intruder "Weird! So weird!"), forcibly kidnapping the cover girl (Eva Mendes, We Own the Night) at the center of it all, dragging her back to his lair for...what horrible plans? No horror, actually, but an astonishing, sublime beauty that jars, it's so incongruous: The segment winds/fades down as a serene tableau vivant, the tumescent, nude humanoid showered in petals and cradled by the photographer's now-maternal beauty to create a most bizarre, yet deeply moving, pietà. (And, if all that wasn't enough, there's also an ebullient tracking-shot, free-for-all musical number, led by M. Oscar playing an accordion to within an inch of its life, to mark midway point of the film in an interlude explicitly labeled an Entr'acte -- literally, an intermission, but more than likely also a nod to René Clair's confrontational 1924 dadaist short of the same name.) It's all as smart -- as unabashedly intellectual and sophisticated -- as can be, but, in addition to having the courage of its convictions and being sufficiently sharp and rigorous to soar high above any danger of tiresome pretension, it's also nonstop fun, impassioned and risky enough to feel like a high-wire act pulled off with aplomb, and -- as the foregoing descriptions can only hint at -- inebriated to its core on all the rich possibilities that movies have flourished in over the bygone century, as well as the ones it might in the future proceed to map out on the same continuum.

For all its surrealness and willingness to go to the most head-scratchingly unusual, bizarre places, however, there's no sense of real disjunction or chaotic confusion to Holy Motors; it's not at all the kind of film that needs "closure," but it attains an immensely gratifying unity as it builds toward a climax that's emotionally penetrating and haunting in its sincere absurdity, all while maintaining a center that holds fast no matter how far-off and obscure its orbiting stories go. That absurd ending posits a most unexpected baseline "reality" (or are these more cinematic "appointments"? Do they ever really end, are the lines that clearly drawn?), the private life from which Céline and M. Oscar actually come when they go out on their jobs, and the film closes at some exquisitely surreal, precise pinpoint where humor and longing, hope and mourning intersect and comingle, all at once and in equal measure. It's not a despairing conclusion, but there is the weariness that must come at the end of a journey that has gone so much farther than we could ever have imagined at the beginning, deep and wide into a "the movies" as a mindset and beloved frame of reference that. Like the medium as it exists in our world, Holy Motors now seem to have done everything and needs to move on -- is perhaps doomed to repeat itself if it doesn't evolve in some radical way. But we're also tenderly, if eccentrically, reminded that our heavy treasure trove of amassed celluloid dreams has still brought us remarkably far, and Holy Motors stands against all anxiety-of-influence odds as a triumph because Carax seems somehow to have fully inventoried, recapped, and taken the medium as far as it will go in any direction at the moment. This great film is a monument to the teeming possibilities of cinema (whether in the form of celluloid or digital images, whether manifesting as emotionally incisive drama or a visceral, anti-realistic thrill ride into the subconscious); a profoundly-considered milestone and measure of the state of the art, and a gauntlet thrown down by Carax -- a challenge to both his viewers and his fellow cinéastes to shake off temptations to indulgent nostalgia or facile irony, take up the torch of cinema (its flame having now burnt down after well over a century of beguiling flicker), and use its rich, receding past as the fuel of new inspiration, reigniting The Movies in a new blaze of glory and marshaling the medium bravely forward into a future as unknown and uncertain as it is full of possibility.

Holy Motors was shot digitally via the high-end RED Epic (digital) camera, and all the clarity; the sharp, vivid colors; and the overall nicely variegated palettes rendered through that process are superbly preserved as they appear on this transfer (AVC/MPEG-4, 1080/24p, at the theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1). Each section of the film has its own "look," and those distinctive qualities shine through perfectly here, with the many dimmer/darker scenes retaining very solid blacks, with no crushing or softness at any point. There is virtually no edge enhancement/haloing, and the transfer appears to be entirely free of aliasing or other compression artifacts. In all, the visual presentation of Holy Motors on this Blu-ray edition does full justice to the film's ingeniously inventive look(s) and allows us to experience its greatness with no distracting flaws or compromises.

Sound:The Blu-ray offers both Dolby Digital 5.1 surround and Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo soundtrack options (the package, at least on my copy, inaccurately indicates DTS-HD Master Audio), either of which offer the film's carefully conceived and layered sound in a manner as clear, vivid, rich, and full as could be hoped for, from low to high. In French with optional English subtitles. (Note: The setup menu on this disc is uncommonly tricky; the graphics and icons are set up in such a way that it is difficult to tell which soundtrack is selected and whether subtitles are turned off or on. In addition, at least on my Sony Blu-ray player, these functions can only be performed on the setup menu, not with the remote control, so some care/caution is in order when performing the setup to ensure that you've actually selected your preferred subtitle and soundtrack options.)

--"Drive In" - The Making of Holy Motors, a 45-minute documentary that intersperses rare behind-the-scenes footage of the elusive Léos Carax at work with his actors and crew; very thoughtful and revealing interviews with cinematographer Caroline Champetier and actors Denis Lavant, Édith Scob, and Kylie Minogue (no one-on-ones with Carax, unsurprisingly); and clips from the film, both in the intermediate processes of being made and in their completed form -- all done in a way that's nicely in keeping with the style and approach of the film itself. An unusually enlightening, creative, and pertinent supplement.

--A 13-minute interview with Kylie Minogue, in which the modest yet forthright Australian pop singer recalls the casual casting process through which she landed her part in Holy Motors; her only slight familiarity with Carax's previous work and how "gentle" he was when it came to their working together; her own more-questions-than-answers response upon seeing the film in its completed form for the first time; and her genuine gratification at the privilege of being asked by Carax to step entirely away from any territory familiar to her. (Once upon a time, in 1996, dark-hearted rock balladeer/fellow Aussie Nick Cave enlisted Minogue for an entirely unexpected but now classic murder-ballad duet, and she describes her role in Holy Motors as the cinematic equivalent of that musical stretch/breakthrough.)

--Both the film's international theatrical trailer and its U.S. theatrical trailer. Either one is well-done, though the international one is more of an honest representation; watching both makes for at least an interesting thumbnail lesson in the divergent assumptions European and U.S. marketeers harbor when it comes to their respective moviegoing demographics.

Holy Motors, the long-awaited return to feature filmmaking of France's onetime next-big-thing director Léos Carax, is pure catnip for anybody who loves movies. The simultaneously mechanical and amorphous, intangible spirit -- the "holy motor" -- of the cinematic medium itself is here presented to us in the form of a metaphorical agency whose venerable but weary representative, M. Oscar (the eternally malleable, manically inspired Denis Levant), travels around in one of what we later learn are the agency's many white limos, playing out cinematic scenarios of various vintages, styles, and temperaments -- all of them perfectly, ingeniously, and gloriously brought off by the film's creator, technicians, and players, each going above and beyond sincere homage to become an inspired, original reinterpretation of various genres and vaguely recognizable dramatic turns that the movies have deposited in our subconscious, never with even a hint of "ironic" subterfuge. This beautifully executed, miniaturized yet astoundingly full-blooded recapping of the continuum of cinema in all its manifestations could in itself have been sufficient to make the film a masterpiece, but Carax goes even further, branching out from the merely aesthetic to delicately ply open the related philosophical questions with which our irrevocably technology- and representation-driven simulacra-world faces us. The film is a marvel, an odyssey through which we can experience all the joys of cinema (as well as its sorrows, as it leaves behind its old projected-on-film form to be resurrected on digital) from both ends -- forward- and backward-looking -- of Carax's finely calibrated telescope. It continuously, unfailingly operates at full throttle on every cerebral, visceral, and emotional level; no picture since Mulholland Drive has looked back through the cinema's past and forward into its murky future at once with such passion and inventiveness -- such unbelievably complementary cleverness and palpable, overwhelming emotional commitment. Holy Motors is a flat-out mind-blowing thrill the first time you watch it, but the subsequent viewings it demands will undoubtedly prove it to be a true milestone, an important marker at a turning point for the medium -- one by which past glories will be remembered, and future developments measured, for a very long time to come. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||