| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

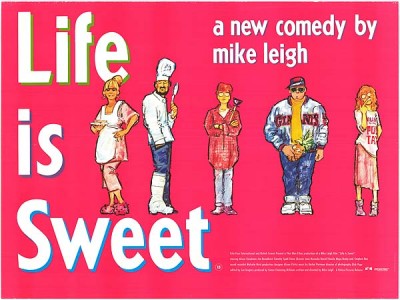

Life Is Sweet: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are from promotional materials and stills provided by The Criterion Collection, not the current Blu-ray edition under review.

If one were forced (against one's will, it would have to be) to pick and choose and split hairs among the near-uniformly excellent, inspired, and distinctive-visioned films of English writer-director Mike Leigh (Secrets and Lies), the arbitrary honor of "greatest of the great" would probably always have to go to his harrowing, biting, almost unbearably impassioned 1993 breakthrough, Naked, in many ways an atypically dark film for Leigh. But the best introduction to Leigh's inimitable cinematic storytelling would probably be something more like the feature that precedes Naked in his filmography, 1991's Life is Sweet, which has just been released by Criterion in a splendiferous new Blu-ray edition. The world of Leigh's films -- almost always a prismatic view of contemporary English life refracted from working-class existence, always observed with affectionate humanity and tenderness cut with an unflinching social consciousness and a carefully channeled humanistic moral sense -- holds together remarkably well, over all of his disparate films, as one whole: Life is Sweet is the daytime to Naked's nighttime, two chapters from an ongoing, unified story told by the same cinematic voice. But Life is Sweet is in a different register; it's possessed of a gentler tone more usual for Leigh's work, where nothing is ever perfect and what's good in the world is always precious and beleaguered, but a certain resilience and connection within and between imperfect people make everything worthwhile after all.

In Life is Sweet, the inelegant but hardy and generous folks who have their resilience and interconnectedness subtly tested and proved are a hard-working family in a modest row house somewhere in London -- a residence that now has a junky, beat-up caravan (that's "trailer" for us Yanks) on eyesore display in the front drive. This dilapidated, disused food-stand truck is the vessel of family patriarch Andy's (Jim Broadbent) -- who's also a chef at his demanding institutional day job -- entrepreneurial high hopes, which are looked upon with bemused, self-consciously futile protest by his too-chipper, inappropriately-laughing, all-around indefatigable wife, Wendy (Alison Steadman), a shop clerk at a second-hand clothes shop specializing in children's apparel; with brutally honest but genuine curiosity by his practical-minded late-adolescent daughter Natalie (Claire Skinner), a plumber's apprentice methodically saving up and planning for a trip to the States; and met with disdainful sneers of "capitalist" by Natalie's pseudo-nihilistic, secretly anorectic identical twin, Nicola (an amazingly unrecognizable Jane Horrocks, of Absolutely Fabulous and Little Voice fame). Nicola, a prime source of this supremely relaxed and confident film's slowly surfacing dramatic conflict, is a wayward idealist whose extreme vulnerability masks itself in inchoate attacks on her family, her would-be boyfriend (David Thewlis), and, most disturbingly, herself.

What would seem to be an incongruous slapstick element (it's actually miraculously part and parcel of the film's overarching tone and themes) presents itself in a parallel subplot involving family friend Aubrey (frequent, shockingly versatile Leigh star Timothy Spall), a would-be yuppie and perpetual up-to-the-minute fashion victim who's somehow got it into his head to open a snobbish Parisian haute-cuisine restaurant; Wendy gamely glams up and pitches in to waitress for the increasingly drunken and depressed, dead-empty opening night, an extended interlude midway through the film wherein Aubrey's dim manchild thickness, already strongly hinted at in Spall's so-broad-it's-actually-nuanced performance, comes to property-damaging fruition, confirming Aubrey's bone-deep haplessness once and for all when it's revealed that he forgot to do any advertising. (In this way, the structure and themes, if not the tone, of Life is Sweet anticipate those of Naked, whose wannabe-yuppie, like Aubrey with his own parallel trajectory intersecting that of the film's wiser and more thoughtful people, has been vindicated and empowered by rampant Thatcherism and is a horrific predator in contrast to Spall's benign, affably deluded and gullible loser, whose errant, superficial, and futile social-climbing values are looked upon kindly and tolerantly by Wendy and Andy as a kind of bizarre personality tic from which their friend helplessly suffers.)

Leigh begins the film at the gentle pace of workaday life, allowing the characters to develop and emerge into our view through apparently random, everyday interactions, which are later revealed to have been carefully placed clues to the increasingly emotionally loaded tensions and conflicts that will come to the fore later on. It's an expertly calibrated, subtle technique, allowing the story to gather speed and intensity almost imperceptibly, drawing out and rendering visible what's propulsive, interesting, and dramatic about "ordinary" life without once compromising the film's relaxed, naturalistic believability. Life is Sweet was Leigh's first collaboration with cinematographer Dick Pope (Thin Ice), without whom he's never made a film since, and although Leigh's visual style is generally of the stiller, more invisible variety, he and Pope do, here as they always have since, create a "look" for Life is Sweet, brilliantly using springtime sunshine and precise domestic compositions to reveal the textures of these people's lives and in what peculiar ways their relationships with each other and within their specific space -- for example, Nicola's "private - keep out" sign on an always-closed bedroom door shot intently from the staircase below and framed tightly within yet other corners and entranceways to highlight her layers of locked-away isolation; or the difficult-to-achieve, intricately blocked static shots in which parents and children move in and out of frame as they go about their daily kitchen-to-sitting-room business -- make their unit and their environment a family and a home. It's through this striven-for simplicity that the film's emotional climax -- a fed-up confrontation between perky Wendy and the aggressively defeatist Nicola -- with its sun-dappled, stark background and extreme, unflinching close-ups of the characters' increasingly agonized faces, takes on a shattering eventfulness; it's "just" a working, exasperated mom having a spat with her indolent and disrespectful adolescent daughter, but as realized by Leigh, Pope, Steadman, and Horrocks, it's powerful, intimate, and revealing enough to rival for a stretch the mother-daughter tinderbox set alight in Bergman's Autumn Sonata.

If Life is Sweet seems a somewhat less focused, pure example of Leigh's artistry than an Another Year or a Happy-Go-Lucky, it more than makes up for it with its own eccentric cinematic embrace of life, hard knocks and too-fragile dreams and all, and especially with the sheer range of what it succeeds at getting its loving arms around; I can think of many films that are as funny (if not funnier) or as moving (if not more so), but very few that manage to be this funny, even silly, and also this profoundly emotional in the space of an hour and 45 minutes (among the very few other such exceptional pictures, Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia comes to mind, despite its whole aesthetic and approach being so far removed from, or even at odds with, Leigh's). It might be one of the more minor ones in Leigh's highly impressive oeuvre (he must be among the 10 greatest living filmmakers), but Life is Sweet is a miracle nevertheless, a tough but tender, funny but loving, deeply humane and emotional but unsentimental treasure. Oh, and that title? It's wholly non-ironic, but the film earns the plain sincerity of the claim made therein; once you've experienced all the territory of life, all the ups and downs Leigh manages to chart so vividly, you feel utterly convinced, at least for a while, that it's absolutely true.

Video:

In comparison to the already-very-good transfer of the film made for Film 4's not-long-ago region-free Blu of the film, this Criterion transfer (an AVC/MPEG-4-encoded, 1080/24p-mastered affair at the original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1), supervised by Leigh's longtime cinematographer Dick Pope, is even better. The multiple shades of naturalistic springtime lighting inside and out, the brighter-side colors of the film, and its half-"gritty," half-serene texture and composure are all done full justice, without a single trace of aliasing, edge enhancement/haloing, or other compression artifacts, and with judicious and responsible use of digital noise reduction (DNR) that doesn't strip away any noticeable trace of vital celluloid-like texture from the experience.

Sound:The disc's DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack faithfully renders the film's original stereo mix with full fidelity, resonance, depth, and balance. From the all-important dialogue to Rachel Portman's omnipresent but perfectly apt and well-integrated score, there's not a moment of audio that goes amiss; it's all crisp, clear, and multilayered, beautifully cleaned up but not over-polished or tampered with, and without any imbalance or distortion whatsoever.

Extras:Feature audio commentary with writer/director Mike Leigh, newly recorded this year. As usual, the enthusiasm, intelligence, and generosity in Leigh's own personality are contagious in their own right, above and beyond those same qualities' plentiful manifestations in the film itself. Well worth a listen, for both enlightenment and additional entertainment.

--An hour-long audio interview/Q&A from around the film's release, which in addition to the commentary is another, more immediate glimpse, through Leigh's articulateness and self-deprecating wit, at the making of Life is Sweet in particular and more generally of Leigh's unusual, improvisatory working methods and career path to that point.

--Five short films made by Leigh for the BBC as a sort of "pilot" for a proposed but never realized series to be called Five-Minute Films. Shot in 1975 but not aired until 1982, this unfortunately abandoned project might have been wonderful. Each of the five shorts -- which, true to the title, run more or less exactly five minutes and recount over various timespans and in different settings and modes the stories of working-class Brits at home, on the job, and in friendship, rivalry, and love -- is rich with Leigh's incisive observation, humor, affection, and delicate, subtle pathos.

--A booklet featuring numerous stills/graphics from the film and containing an appreciation/essay by critic and longtime Mike Leigh aficionado David Sterritt.

Life is Sweet is the great British writer/director Mike Leigh at his most blatantly comic, but in this case, that only means that the acutely observant social consciousness and the tender, consistently surprising and moving emotion he shows us in his thick-skinned working-class characters is just another hue in a broader, brighter palate than he would use for later, darker, more droll and/or dramatic masterworks like Naked and All or Nothing. Somehow, on this earlier sojourn into Leigh's world (only his third theatrical feature in a then already two-decade career more focused on TV and stage work), the slapstick antics of Leigh regular Timothy Spall's chef/foolishly aspiring haute-cuisine restaurateur coexist complementarily with the lesser but more grounded gastronomic ambitions of a working-class chef (Jim Broadbent), his ditzy but resilient wife (Allison Steadman), and their twin daughters, the scowling slacker Nicola and the pragmatic apprentice-plumber Natalie (Jane Horrocks and Claire Skinner, respectively, in career-making roles), who together comprise a family whose lurking tensions and ultimate strength Leigh reveals with such narrative and visual respect, intuitiveness, and preternatural understanding of the complexities of human emotion and behavior that it moves you to tears, even though it may have had you in stitches two scenes ago. It's a more diffuse, ambling film than Leigh's absolute-best work, but it's still an unqualified delight; the title, as it turns out, isn't at all ironic, but Leigh and his cast and crew well earn the film's overarching sense of pragmatic optimism, which is not just encouraging and infectious but -- more importantly and unusually -- rendered convincingly, substantively real through Leigh's unique skill and insight, the care he takes in every sense of his story and his characters. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||