| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

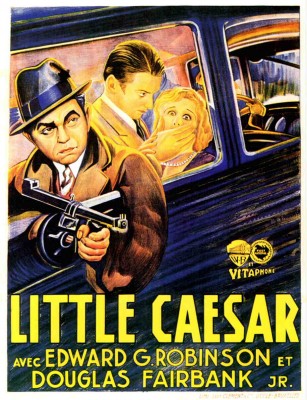

Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics (Little Caesar / The Public Enemy / The Petrified Forest / White Heat)

Please Note: The images used here are from promotional materials and stills provided by Warners/Turner Classic Movies and other sources, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

The legend goes something like this: In 1954, Warner Brothers repackaged two twenty-year-old successes -- Mervyn LeRoy's Little Caesar and William Wellman's The Public Enemy, both 1931 -- as a double bill in hopes of reintroducing a new generation of moviegoers to the dangerous, hard-hitting appeal of those wildly successful items from the Warners vault -- two premium exemplars not only of a near-proprietary studio style that went for zippy, gritty brevity and realism but, most particularly, of the endlessly fascinating subgenre of that streetwise realism that would come to be known as the gangster picture. It was upon the occasion of that two-for-one re-release that a 10-year-old New York kid named Martin Scorsese got his first intoxicating whiff of the troubled (a)morality, violence, ambition, and charisma of the silver-screen gangster as a catalyst for dizzying, riveting cinematic storytelling; to hear Mr. Scorsese tell it, as he does with his usual impassioned and self-deprecating charm in several supplementaries included in WB's new The Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics Blu-ray set, this was the moment he received the cinematic legacy from which he would build a bridge forward to our era when he made 1990's Goodfellas, the centerpiece of a concurrent Ultimate Gangsters: Contemporary box), the definitive contemporary gangster film, which he evidently fanned from the embers Cagney left behind at the infernal climax of one of the set's offerings, Raoul Walsh's 1949 gangster masterpiece White Heat. It's a legacy that the home-viewer cinephile now has the privilege and opportunity to add to his or her collection in the form of the conscientiously spiffed-up editions of four Warners classics -- the aforementioned Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, and White Heat, along with 1936's The Petrified Forest -- included in this collection, offering up a concise, diverse survey of this specific, perpetually alluring movie subgenre while coming at you like four clean, sharp, rapid shots fired across the screen.

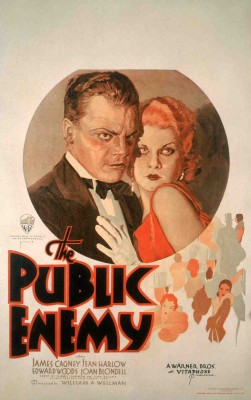

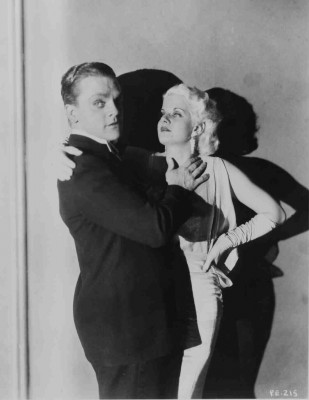

It was the notorious prohibition of the 1920s, and its consequent booming black market for spirits, that gave rise to the heavily Al Capone-inflected movie archetype of the gangster presented to us by Little Caesar and The Public Enemy, two early-Depression/early-talkie pictures bursting with the timely, tense mixture of an American dream of prosperity and a severe post-market-crash doubt about the likelihood of hard work and playing by the rules ever making that dream a reality. That's certainly a doubt to which the diminutive but deadly Rico/"Little Caesar" (Edward G. Robinson) has long ago succumbed. A small-time crook making his living by knocking down rural gas stations, Rico convinces his more straight-edged partner, Joe Massara (Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.), that his remorseless murderousness and ambition would be better capitalized upon in the big-city gangland, and so the pair enter the urban milieu where their respective hopes and dreams -- Joe's innocuous gravitation toward a stage career as a dancer, fancy clothes, and a pretty but loyal woman (Olga Stassoff), Rico's more single-minded and dark-hearted lust for sheer power, privilege, and cowering, intimidated respect -- eventually put them at treacherous odds when Joe decides to go straight but Rico's insistence that his partner aid and join him on his cutthroat rise to the top, no matter which bosses he has to double-cross or rub out to get there, leaves the now-successful dancer torn between his longtime friend on one hand, on the other his faithful mistress and the cop (Thomas Jackson) bent on bringing Rico down. But if the conviction that the straight and narrow is for suckers is one Robinson's Rico seems to have been born with as a near-reptilian villain, we get a deeper picture of such an attitude in the clash between The Public Enemy's Tom Powers (Cagney) and his good-boy brother, Mike (Donald Cook), whom we follow from their childhood in a strict policeman's home as Mike studies, work hard, and fights in World War I and Tom finds a different family of petty-thieving delinquents, including his best pal, Matt Doyle (Edward Woods), and will eventually join in on the exploitation of prohibition and claw his way to the top of the luxurious-living, hardbitten gangster heap. Or die trying; Tom Powers's awful demise makes for one of the most memorably tough endings in movie history, evading the tidier reap-what-you-sow moralism of Rico's end in Little Caesar and taking on a more tragic dimension as the repercussions of his violent way of life for his family are starkly, unsentimentally, and unflinchingly made manifest in the film's brilliant, harrowing final moments.

Little Caesar is a very solidly and supply crafted specimen of the studio system's smart, well-oiled storytelling machine; the almost journalistic matter-of-factness of Francis Faragoh's script (after the popular novel by W.R. Burnett) moves the film along at a brisk clip, and director Mervyn LeRoy (I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, Gold Diggers of 1933) guides matters with a craftsman's dab hand: Some impressively fluid camera movements (such as a graceful, symmetrical track in through drawn doorway curtains, a shot as elegant as the New Year's bash it reveals), composition (a receding row of lackeys perfectly aligned as they hang on boss Rico's words, Rico posing pridefully on a stage in long shot as a foregrounded newspaper photographer memorializes him with a flash, surely a touchstone moment for Scorsese's own flash-filled rise-to-notoriety scenes), and mise-en-scène (the final shootout, in which the machine-gun bullets fired by the cops riddle Rico as they pepper holes through a billboard advertising Joe Massara's upcoming stage spectacle). But it's The Public Enemy that, only a year later, develops the gangster iconography and visual/aural storytelling by leaps and bounds, taking the torch left behind by the gunned-down Rico and running with it. It's true that director William Wellman (Wings, the 1937 A Star is Born had a script (by Harvey Thew, based on firsthand Al Capone observers Kubec Glasmon and Jim Bright's novel Beer and Blood) that ventures deeper and wider than Little Caesar's, but Wellman's true-blue-auteur status as compared to skilled and able hired hand LeRoy shines through in dozens of flourishes and touches that gel beautifully and accrue a magnificent power, among which: an extreme-low-angle POV shot in which Cagney's croney's car, viewed from below, seems to run right over us; the atmospheric set piece in which Cagney, in a downpour, advances ominously toward the camera as he carries out his mission of vengeance whose gunfire and bloodshed are kept evocatively offscreen but well within hearing distance; and the film's recurrent use, from start to finish, of the popular tune "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles," at different tempos and in different orchestrations to match Tom Powers's shifting moods and fortunes, culminating in the film's powerful final shot of a phonograph needle bumping, repeatedly and terminally, in the runoff grooves of an "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles" record that's been playing in the Powers's sitting room -- a most witty and effective concluding image memorializing the film's ingenious use of music, one of the most modern and inspired devices of all four films.

Flash forward to 1936: Prohibition has given way to the interminable Depression, and some hot new Warners star-blood -- in the form of Bette Davis and Humphrey Bogart -- are thrown into the mix with established matinee idol Leslie Howard for the studio's big-screen iteration of a prestigious stage property, Robert Sherwood's The Petrified Forest. This picture is decidedly the odd man out of the group; it's the least purely "gangster" effort here by far, comprising instead a remarkable hybrid of swooning silver-screen romance (which plays out between small-town diner scion Davis, a girl with literary ambitious and worldly ideals, and the exotic, British, pre-existentialist-philosophizing literary type, Howard, who hitchhikes his way in her tiny, remote Arizona desert town) with outside-the-law fugitives in the form of Bogart -- in arguably his first iconically "Bogartian," gruff and taciturn, role -- as the gangster Duke Mantee, who shares a less wordy version of the Howard character's despair and whose band of murdering/thieving outlaws holds an array of characters hostage in Davis's diner as they hide out and strategize. But it's a fine film in its own right, and it earns its place in the set as an unpredictable marker of the gangster genre's surprisingly elastic further reaches; it's much wordier and less realistic (the "desert" backdrops are brazenly artificial, matte paintings like that indelible, better-than-real "New York skyline" in Hitchcock's Rope) than the other films proffered here, but the director, stalwart movie veteran Archie Mayo, and his cast and crew find the right visual and performative tone to make Sherwood's poetic and philosophically-tinged dramatics work in a heightened-reality cinematic style, and the sweet-and-sour juxtaposition of Howard/Davis glamor and Bogart toughness reveals some surprising meeting points and overlaps, with the result an odd and eccentric, yet perfectly captivating and effective, harmony between seemingly contradictory genres, stars, and styles.

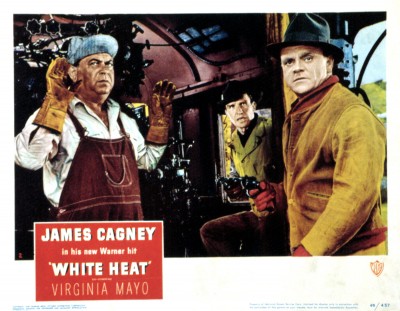

The Ultimate Gangster Collection: Classics's coda is Jimmy Cagney's bold and brilliant resurrection of his gangster persona after years of (quite successfully) struggling against the typecasting, and it's also the finest film of an already choice bunch -- director Raoul Walsh's (The Roaring Twenties, They Drive by Night 1949 gangster picture to end all gangster pictures, White Heat. Of course, Walsh, who had been in the business as an actor and filmmaker since the silent era, had had years of his own experience and, by then, dozens of fantastically fatalistic film noirs in which to simmer White Heat's deep, dark wet-asphalt-at-nighttime aura; this movie is where the best and most brutal of the gangster movie and the film noir meet and egg each other on to a definitively apocalyptic finale. Cagney stars as Cody Jarrett, a merciless heist-master and ringleader as cold-blooded as he is certifiable, complete with a steel-spined mother (the wonderfully brusque Margaret Wycherly) facilitating his delusional neuroses and helping him keep his traitorous band of gun-toting robbers, along with his hard-boiled and wandering-eyed moll, Verna (Virginia Mayo) in check as the gang flees a train robbery turned foul and deadly, a crime for which Jarrett will face the gas chamber if his responsibility for it is proven. Jarrett is predisposed to random, sudden, seizure-like fits of pounding-headache psychosis that momentarily debilitate him, a vulnerability exploited by undercover man Hank Fallon (Edmund O'Brien), who gets himself locked up with the scheming Jarrett to befriend and betray the frighteningly mercurial boss and bring him to capital-punishment justice.

But the way Jarrett goes is something more terrible and nihilistic than any such lawmen's plan, and our spiral down (or is it up to, as Ma Jarrett always intones to little Cody, the "top of the world"?) with Jarrett is masterfully orchestrated by Walsh as a nonstop wracking of the nerves, the increasingly frantic and demented struggle of Jarrett's mad animal as an already claustrophobic web of mistrust and treachery pulls ever tighter to ensnare him. We see Walsh's mastery in microcosm in the propulsive, elaborate action sequences he puts together with such adroit grace -- a jailhouse attempt on Cody's life viewed from the same overhead angle as the bit of machinery meant to crush him, the car-chase pursuit of Ma Garrett through suburban L.A. by her son's would-be captors -- and in many more subtle ways throughout as the director hurtles us and Jarrett toward his inexorable fate, creating an ever more tense, combustible aura that renders the film's self-immolating, explosive climax at a gasworks both inevitable-seeming and, as awful as it is, tremendously gratifying. Of all the wallops packed by this collection, White Heat's is the strongest, most perfect knockout of all; it wouldn't be until the arrival of Scorsese's neo-gangster movies decades later that the genre would again be brought to life with such panache, such ambivalent yet strong currents of fascination, or such fiercely ignited cinematic skill, inspiration, and passion.

This little package couldn't possibly claim to represent all the classic movies that could be slotted into the gangster genre, but as a succinct sampling of prime specimens, it skims off nothing but the cream, compiling together some of its most famous, celebrated, exemplary titles, whose thematic similarities make them seem natural companions, but whose differences do justice to the diversity of cinematic tones, styles, and approaches that the genre afforded its filmmakers, whether they were just visiting gangland or had made it their home. Moment for moment, thrill for thrill, from rise to fall to charisma to villainy, The Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics is a far-ranging yet taut, perfect little encapsulation of what has always been -- and continues to be -- the allure of the gangster on celluloid, whose criminality our endless simultaneous enthrallment with and moral rejection of is a paradox best experienced in the dark as we gaze, appalled and envious, at the flickering images of their unbound egos, lawless liberties, and thrilling misadventures.

Video:

The picture quality of this set -- with each film presented, AVC/MPEG-4 encoded and 1080p-mastered, at its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.37:1 -- ranges from very good to excellent. Considering the age of some of the materials, the extreme rarity of any flicker, scratches, or other signs of wear is remarkable; the contrasts, darks, and lights in each of these black-and-white productions is stunningly well-preserved and -presented. On the compression-artifact front, there's virtually nothing: No aliasing or edge enhancement is discernible at any point, and -- as we've come to expect from Warners, who by now have earned quite a good name for the eminently respectful treatment they usually give on Blu-ray when withdrawing gems from the vault -- there's a scrupulous avoidance of overusing digital noise reduction (DNR), leaving the films with virtually all of their truly cinematic, celluloid-like texture intact. In all, the look of each of the films as they appear here is praiseworthy, most likely as high-quality yet faithful as possible.

Sound:All of these films, save for White Heat, are a) quite old and b) from very early on in the sound era, so there's an endemic roughness to their soundtracks, as well as some mild hiss often heard in their backgrounds, particularly noticeable in The Petrified Forest. However, a quick comparison to the prior WB DVD edition of that film reveals the same issue, and given the fine care taken on the visual side of the package, one trusts that these aged soundtracks have been cleaned and polished to the full extent feasible, and apart from that steady background hiss on the earlier films, and everything is certainly clear, audible, and as resonant as can be; no actual distortion, drop-outs, imbalance, or other flaws mar the discs' faithful presentation of the film's original monaural sound via DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 tracks.

The set is packed with extras to immerse us in the films' cinematic, social, and historical contexts, with all of the supplements that were featured on each film's prior stand-alone WB DVD release fully present and accounted for. These grandfathered-in extras include:

--On Little Caesar: a) Feature audio commentary by film scholar Richard Jewell (a little heavy on the plodding, superficial plot description and light on context and deeper insights, particularly visual, though Jewell does have tidbits from the film's production, release, and reception to offer); b) A "Warner Night at the Movies" program from the film's 2005 TCM airing, featuring an introduction by critic Leonard Maltin; the trailer for the upcoming release Five Star Final, also starring Robinson; a newsreel with a contemporaneous interview with the bereft moll of dead gangster "Legs" Diamond; The Hard Guy (6 min.), a dramatic short subject starring Spencer Tracy as a struggling, Depression-beleaguered family man; a Merrie Melodies cartoon, Lady Play Your Mandolin, (6 min.) designed to promote the 78 RPM and sheet music versions of the title tune, here voiced by an animated menagerie of animals from mice to apes; c) "Little Caesar: End of Rico, Beginning of the Antihero," (16 min.), also for TCM's airing of the film, featuring critics/scholars like Robert Sklar and filmmaker Martin Scorsese placing the film as the first big gangster-picture talkie while thumbnailing the evolution of the movie gangster from the silent era up through that point; d) The film's theatrical trailer; and e) the brief disclaimer/foreword that ran with its 1954 re-release, positing the film as a socially responsible wake-up call.

--On The Public Enemy: a) Feature audio commentary by film scholar Robert Sklar, which offers a knowledgeable production history and contextualization, with a particular emphasis on Cagney (on whom Sklar wrote a book), but again with a paucity of visual analysis; b) a period-tailored "Warner Night at the Movies" program, introduced by Leonard Maltin, with the theatrical trailer for Blonde Crazy (another Cagney vehicle); a newsreel on the apparently quite novel "female athletes" preparing to represent the U.S. at the '32 Olympics in Los Angeles; The Eyes Have It (10 min.), a comic short subject featuring the beloved vaudevillian/puppeteer Edgar Bergan and his dummy, "Charlie McCarthy," in an optometry-related sketch; and Smile, Darn Ya, Smile (7 min.), a Merrie Melodies featuring the same little singing mouse seen in "Lady, Play Your Mandolin," along with his female companion; c) "Beer and Blood: Enemies of the Public," (19 min.), the introductory short documentary, again with commentators Scorsese and Sklar, et. al, from TCM's 2005 cablecast of the film; d) the film's theatrical trailer; and e) the same re-release disclaimer/foreword as Little Caesar (as Scorsese mentions in the documentary piece, the films were re-released together as a double bill in 1954).

--On The Petrified Forest: a)Feature audio commentary by Humphrey Bogart biographer Eric Lax, probably the briskest and best-integrated commentary here, though still more biographical/historical/production-recounting than incisive on the film itself; b) A 1936-centered "Warner Night at the Movies" from TCM's 2005 showing of the film, with an intro by Leonard Maltin and featuring the trailer for Bullets or Ballots, starring Little Caesar's Edward G. Robinson and The Public Enemy's Joan Blondell; a newsreel recapping 1936's biggest news (death of King George V, the reelection of FDR); Rhythmitis (20 min.), a musical-comedy short featuring tap dancer Hal Le Roy; and The Coo Coo Nut Grove (7 min.), a Merrie Melodies cartoon, in color, set in a nightclub and rife with delightful animated caricatures of the period's movie stars. c) "The Petrified Forest: Menace in the Desert (15 min.), TCM's introductory doc for their 2005 cablecast of the film, featuring interviews with Lax and the renowned, late critic Andrew Sarris; d) the 1940 Gulf Screen radio broadcast of The Petrified Forest, with the voice of Bogart in addition to those of Joan Bennett and Tyrone Power in the Davis/Howard roles; e) the film's theatrical trailer.

--On White Heat, a) Feature audio commentary by Dr. Drew Casper of USC (who's also all over the TCM documentaries and whose breathless, overdramatic presentation I personally find off-putting, though he reigns that in a bit here to apply his knowledge of Cagney, Warners, and the films and culture of the period, though again, precious little visual/cinematic analysis is brought to bear); b) the '49 rendition of the "Warners Night at the Movies" program TCM ran with the film's 2005 cablecast, with the standard intro by Leonard Maltin and featuring the trailer for King Vidor's The Fountainhead with Gary Cooper and Patricia Neal (based on the novel by neoconservative/"libertarian" hero Ayn Rand); a newsreel trumpeting the surprise presidential victory of Harry S. Truman; a Merrie Melodies cartoon, Homeless Hare (7 min.), a classic Chuck Jones entry with Bugs Bunny; So You Think You're Not Guilty, one of a series of one-reel comedies centered around put-upon average-American-guy "Joe McDoates" (future George Jetson voice George O'Hanlon); c) "White Heat: Top of the World (17 min.), TCM's 2005 documentary concurrent with their presentation of the film, once again featuring Sklar and Scorsese, with input from Cagney's female costar, Virgina Mayo; and d) the film's theatrical trailer.

In addition, a bonus DVD contains the 2008 TCM documentary, directed by Constantine Nasr, Public Enemies: The Golden Age of the Gangster Film, with narration by Alec Baldwin over a panoply of snippets from gangster films from the silent era to today, with archival interviews with Edward G. Robinson, William Wellman, Raoul Walsh, Joan Blondell, and others, along with critic Richard Schickel, Scorsese, and Bonnie and Clyde screenwriter Robert Benton. This disc also contains a collection of four gangster-themed Merrie Melodies/Looney Tunes cartoons: I Like Mountain Music (1933, 7 min.); She Was an Acrobat's Daughter (1937, 9 min.) which incorporates a hilarious Petrified Forest spoof; Racketeer Rabbit (1946, 8 min.), and Bugs and Thugs (1953, 7 min.), the latter two offering prime Bugs Bunny hijinks.

The cherry on top is the collection's packaging, a sturdy outer cardboard sleeve housing the five Blu-rays and one DVD together in a single, well-designed and secure snap case with inner hinge as well as a 35-page hardbound collector's book packed with iconic stills from the films and text that succinctly sums up where these pictures came from and their enduring appeal.

"Ultimate" might be a tad on the hyperbolic side, but no matter; the four-film Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics easily lives up to the "classics" part, and if the inclusion of equally vital films from the period covered, like Howard Hawks's Scarface, Michael Curtiz's Angels with Dirty Faces, or Raoul Walsh's own The Roaring Twenties might have made it more "ultimate," the set is nevertheless an impeccably excellent survey of both the gangster genre and of the Warners studio style from 1930 to 1950. Whether it's the one-two punch from 1931 with Edward G. Robinson menacing the screen in Mervyn LeRoy's Little Caesar and Jimmy Cagney shooting his way to the top and falling so, so hard in William Wellman's The Public Enemy; Humphrey Bogart's unforgettable 1936 star turn as the world-weary gangster who crashes the swooning romance between Bette Davis and Leslie Howard in Archie Mayo's deliriously artificial, gorgeously studio-bound The Petrified Forest, or Cagney returning for his gangster swan song as he literally sets the screen ablaze in Raoul Walsh's superlative White Heat from 1949 (which, when all is said and done, really is the ultimate gangster picture), this succinct little package of studio craftsmanship is bursting with innovative, exciting direction, iconic screen presence, energized (and then unprecedentedly high) Hollywood Golden Era production values and standards, and all the vicarious thrills of living fast, loose, and bad in a world where playing by the rules gets you nowhere and you've gotta angle and kill your way into the big time. They all look and sound wonderful, too, as presented in these new Blu-ray editions, and come heavily laden with interesting extras to further open the films' windows into a peculiarly American cultural, social, and historical legacy. Each one of these pictures on its own would easily come highly recommended, but as a group, they gather enough momentum and constitute a foundational and exemplary enough block of elemental cinema to be classified DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||