| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Andy Hardy Film Collection: Volume 2 (Warner Archive Collection), The

A year and half later, and the series is complete. Warner Bros.' Archive Collection line of hard-to-find library and cult titles, has released The Andy Hardy Film Collection, Volume 2, a five-disc, ten-movie gathering that includes: 1937's A Family Affair (the series' kick-off), 1938's Judge Hardy's Children and Love Finds Andy Hardy, 1939's The Hardys Ride High and Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever, 1942's The Courtship of Andy Hardy and Andy Hardy's Double Life, 1944's Andy Hardy's Blonde Trouble, 1946's Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, and the belated finale, 1958's Andy Hardy Comes Home (in anamorphic widescreen). In my January, 2012 review of The Andy Hardy Film Collection, Volume 1 (which featured six Hardy movies: 1937's You're Only Young Once, 1938's Out West with the Hardys, 1939's Judge Hardy and Son, 1940's Andy Hardy Meets Debutante, and 1941's Andy Hardy's Private Secretary and Life Begins for Andy Hardy), I lamented the Archive's hopping-around the Hardy titles, not presenting them in chronological order. However...at least now all the movies are finally on disc, and that's great news for fans of this wonderful series (well...almost all of them are here: 1940's short subject, Andy Hardy's Dilemma, is M.I.A., unfortunately). Original trailers for all the movies except Love Laughs at Andy Hardy, and a few other bonuses for Love Finds Andy Hardy (from the out-of-print 2004 Judy Garland Signature Collection release) round out these fine-looking black-and-white transfers.

As I wrote in my earlier review, the Hardy series has always been a bittersweet, fascinating source of nostalgia for me from all those years ago when the Andy Hardy movies were a staple of afternoon and late, late show movie programs (I never missed Detroit's Channel 7 Andy Hardy Theater movie program every Sunday morning at 8:30am). For a movie-crazy kid like myself who was all-too aware of life outside "the box," irrepressible teen Andy, wise, kindly Judge Hardy, loving mother Emily, and their mythical Midwestern small town of Carvel, hold a dear place in my early movie memories, when, if you were young enough, you could almost believe, in some strange, parallel black-and-white movie world, that such a place and a family had actually existed. Often referred to as "America's first family" in the press and by moviegoers back in the late 1930s and early 1940s, tens of millions of Americans, tired of the Depression and fearful of the inevitable world conflict inching its way towards the States, the plain, average Hardys, in their own homey, rock-solid-valued way, showed their audiences how to meet everyday (and melodramatic) challenges with steady resolve, teamwork, understanding, and of course, love. Contrary to a favorite canard of many historians and social commentators, I've never believed that there was a time in our history when Americans were "naive" about the realities of their lives and the society in which they lived, but there were (and are right now) certainly times when social customs demanded that they appear naive about life's more unpleasant aspects--or perhaps more correctly, deny or keep quiet about those realities in favor of a more socially-accepted facade. Folks living in the midst of the American Depression were more than wise to how hard and often unfair life was outside those hallowed movie halls, but this was still a time when a vast majority of Americans could accept melodrama and sentimentality "innocently," if you will, fully acknowledging the artifice that went into utilizing those elements, but also accepting them as valid dramatic vehicles for emotional expression, without pejoratively sneering at them with cynicism and irony, as so many sadly do today.

Most of the Hardy audiences probably knew that M-G-M's studio head Louis B. Mayer was feeding them corn in this series, but importantly, he was doing so with an absolutely straight face, without trying to insult them. And they responded in kind, embracing the Hardys unequivocally for what they were: a fictional, idealized portrait of what many Americans wished they were. With that, Mayer and M-G-M's team fulfilled the goals of true "dream-making," where the product was perfectly realized and accepted between movie factory and escapist audience. Much has been written about how the Hardy series was fueled and shaped by the detailed, often-times manic attention of Mayer, who insisted that the sequels honor (and idealize) motherhood, small-town values, American can-do-it-ness, and respectful, loving understanding between impetuous-but-good-hearted sons and wise, forgiving fathers (the latter no doubt how Mayer saw himself with his "immature" stars). Was this how Mayer, an Ukrainian-born Jew and naturalized American citizen via stops in Great Britain and Canada, grew up in St. John, New Brunswick? No...but like many artists (and Mayer the mogul and executive was an artist, just as surely as were his directors and writers and actors), Mayer was able to take his memories and form them into something new, a version in this case of what perhaps he wished his boyhood to be, while creating a vehicle to proselytize his vision of an American society that obsessively accentuated the positive, while eliminating almost completely all of its negatives (having just finished reading a fascinating collection of diary entries from actor Richard Burton, I was amused to see a notation he entered about his disappointment in visiting bustling Phoenix, Arizona in the early sixties--he expected it to look like his movie-inspired American small-town ideal: the mythical Carvel).

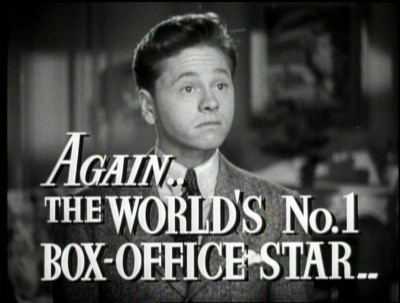

Begun innocently enough as just another "B" programmer out of M-G-M's 52 films-a-year schedule, the first Andy Hardy film, 1937's

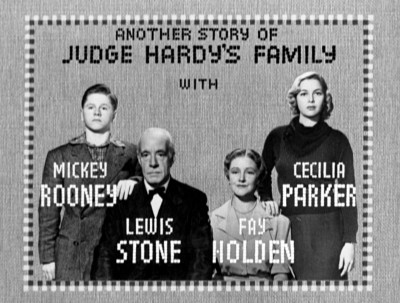

Barrymore, one of Mayer's favorite actors, declined to participate in the sequel, due to the ignominy of being typecast in a "B" programmer (but more likely because of the dough), and Thomas Mitchell (It's a Wonderful Life's absent-minded Uncle Billy) was tested, but eventually Mayer went with courtly, suave Lewis Stone of Grand Hotel fame to take on the Judge Hardy role. Rooney's part was beefed up from the previous outing since peculiarly (at least to Metro executives who heretofore never thought of teenagers and children as a ticket-buying force to be reckoned with), he seemed to drive the kids nuts with his wholesome, all-American, hyperactive shenanigans (setting a precedent for the youth-pandering studios that we're still dealing with today). With veteran producer Carey Wilson now shepherding the potential series, and director George B. Seitz in the director's chair for some time to come, You're Only Young Once was rushed into production, and premiered in November of 1937 (just six short months later), exceeding all box office expectations. Mayer had a bona fide phenomenon on his hands and he ran with it, eventually churning out 14 more Hardy entries before the series proper was cancelled in 1946 with Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1958's Andy Hardy Comes Home was a belated, unsuccessful entry by producer Rooney to revive the series). No one knows for sure exactly how much those first 15 Hardy films actually made, since M-G-M and Mayer (as well as the other studio moguls) were notorious for hiding actual gross and net figures lest their stars realize their true earning potential. However, conservative estimates at the time put the series' total earnings back to the studio at well over ten times their above-and-below line costs--an astounding figure (in 1939, at the height of the series' popularity, M-G-M's net profits were 9.3 million...4 million of which came solely from the last three Andy Hardy pictures released, each of which was still produced for under $300K). By 1939, Mickey Rooney--forever associated with Andy Hardy (probably to the detriment of the rest of his career)--was the number movie star in the world (for three straight years), with the Hardys the single most influential image of the "typical" American family ever perpetuated on the world's movie screens.

A FAMILY AFFAIR

Construction company owner Hoyt Wells (Selmer Jackson) and newspaper editor Frank Redmond (Charley Grapewin) have a bone to pick with Carvel's Judge James K. Hardy (Lionel Barrymore): why is the Judge sticking with an injunction against the town's job-producing aqueduct project? Judge Hardy calmly insists it's out of his hands because rival newspaper owner Oscar Stubbins (Harlan Briggs) initiated the suit against the project that would drain off Carvel's river for outlying communities and states, and no amount of threats--including Redmond's warning that the town's political machine will endorse someone else for judge on Thursday--is going to make him subvert the law. Meanwhile, back at Judge Hardy's home, domestic turmoil disturbs the usual Midwestern peacefulness. Eldest daughter Joan Hardy Martin (Julie Haydon) has become involved in a potentially ruinous scandal: she was caught by her husband, Bill Martin (Allen Vincent), in a local roadside inn with another man (Joan insists nothing happened outside of her friend's kiss). Younger sister Marion Hardy (Cecilia Parker) has returned from school only to present friend Wayne Trent III (Eric Linden), a "pick-up" she made on the cross-country train. Trent is an engineer coming to Carvel to work (he thinks) on the aqueduct project. And youngest son Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney) is being forced by his mother, Emily Hardy (Spring Byington), to attend a party with girls, escorting against his will former kindergarten pal, Polly Benedict (Margaret Marquis), whom he hasn't seen in over ten years. When Judge Hardy refuses to rescind the injunction even after Stubbins, having been paid off, requests it withdrawn, he's in for the political fight of his life...with his daughter Joan's marital indiscretions used as a weapon against him.

Odd-man-out bookend like the Hardys' final entry, Andy Hardy Comes Home, with no Judge Hardy in sight, series opener A Family Affair is most notable in the Hardy line for its one-shot cast and for its harder-edged scenario. As I wrote above, M-G-M and producer Sam Marx had no idea, let alone intention, of creating a teen-and-family friendly franchise with this little "B," so a darker tone, focused on political corruption and the sexual indiscretions of the Hardy daughters, is notable, while future series headliner, Mickey Rooney, is strictly relegated to the sidelines. Whereas later entries focused almost exclusively on Rooney's mostly humorous romantic tribulations (to the delight of his rabid teen audiences), A Family Affair is quite serious in nature, acknowledging the part dirty political machinations and sexual infidelity have on small town life. Barrymore's judge knows the game these power-hungry men play, and he's willing to fight them tooth and nail, if necessary (I love Barrymore sneering, "You've got nothing on me!" to his blackmailer), even going so far as to physically assault his foes if he feels it's called for...something that would never happen in the subsequent movies starring grandfatherly Lewis Stone as the judge. Blatant infidelity (you can argue degree...but daughter Joan was at that local roadhouse inn, and she did kiss another man in a paid-for room) is also brought forth, along with divorce (pregnant Joan mentions quite a few couples from "the fast crowd" splitting up), and the frowned-upon forwardness of Marion's relationship with her beau (Andy calling it a "pick-up" has a lot of connotations), are themes that the later entries wouldn't touch in this (relatively) realistic manner.

It's always guess work, at best, to consider what would happen in a long-running movie series if a certain actor continued on with a role (my favorite toothache to worry is lamenting George Lazenby's fantastic one-shot Bond entry), but it's still hard to imagine Lionel Barrymore soldiering on as kindly Judge Hardy. Barrymore, looking decidedly seedy, not folksy, seems here more cynically humored by his acknowledgement of political corruption, and ironically bemused by his family's tribulations, whereas Stone was always indignantly offended by the various crooks who tried to fleece him, and wisely, benevolently bemused by his family's tribulations. In other words, you don't get a lot of reassuring warmth off Barrymore. Spring Byington, in the midst of starring in her own Jones Family series, is fine (if a little standoffish) as Emily, but she has little do here so it's difficult to tell. Julie Haydon's Joan Hardy character would be dropped without explanation in all the subsequent Hardy movies, an unnoticed streamlining move that just confirmed that her character was unnecessarily duplicating the better-known Cecilia Parker's Marion (Parker was second-billed here). As for "The Mick," he gives A Family Affair its only bounce, acting like a smart-ass on the phone, or grousing and whining to his mother when forced to date girls. His first scene with one-shot-only Margaret Marquis as Polly Benedict is a blueprint for subsequent romantic encounters for the character: gently humorous at the expense of brash-but-inexperienced Andy...but never mean-spirited (that would come later, and unwisely, in the series). Had not exhibitors and M-G-M scouts reported back to Mayer and Marx the visceral reaction pint-sized fireball Rooney was able to elicit from his surprisingly sizeable audiences, the series probably would never have gone past this first oddball outing.

JUDGE HARDY'S CHILDREN

After dispensing a little home-town justice for some punk high school kids distributing rebellious, anti-authority leaflets protesting the dismissal of Carver High's star football player, Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone) receives attorney J.J. Harper (Donald Douglas), with the Department of the Interior. Harper has an astounding proposition for the judge: Washington D.C., concerned about utility monopolies in the Midwest, wants Judge Hardy to chair a commission on the matter for a fee of $200 a day, plus expenses, for his family's stay in D.C.. Flabbergasted, the Judge accepts, and the Hardys are off to the nation's capitol, with Marion (Cecilia Parker) leaving behind boyfriend Wayne Trenton (Robert Whitney), who's been pressing Marion about marriage, and with Andy (Mickey Rooney) leaving behind steady girl-next-door Polly Benedict (Ann Rutherford), who laments make-out-crazy Andy's lack of culture. Once in Washington, Andy falls hard for Suzanne Cortot (Jacqueline Laurent), the tightly chaperoned daughter of a French envoy, while Marion is dazzled by slimy-smooth D.C. insider couple Maggie and John Lee (Ruth Hussey and Jonathan Hale). What Marion doesn't know, however, is that Maggie and John are working for the very power company that is being investigated by Judge Hardy...and their interest in Marion has an altogether more sinister purpose.

The third entry in the series, Judge Hardy's Children certainly sounds like it will focus on both Andy and Marion's trials and tribulations in Washington, D.C.. However, it's clear by this point that Mayer wanted his Top Ten box-office attraction Rooney front-and-center, so while Parker gets her subplot about "dazzling" sharpies duping her to blackmail her father, many more scenes deal with Rooney's girl trouble and his parental reckoning for having secretly authored that anti-authority leaflet (once second-billed Parker is now fourth...from here on out). Written again by Kay Van Riper, Judge Hardy's Children reinforces the New Deal status quo that Republican Mayer sought for such mass-appeal fare (he knew which way the current tide flowed), showing government here to be the investigator/enforcer for rooting out corruption, rather than it and its representatives being corrupt, as it was in A Family Affair. Here, the powerful private utility company hopes to use blackmail to force naive-but-well-meaning outsiders like Judge Hardy, who are in Washington to help the country, to bend laws to their advantage (no comment from the movie, of course, on that outrageous fee being paid to the Judge being part of the problem in D.C.). This conflict is of course amplified by Andy's admission to his father that he wrote that leaflet, and the Judge's genuine hurt at Andy's foolish behavior. The subsequent trip to see the Constitution and Mount Vernon is not only to teach Andy not to rebel, but also teach the audience that "government knows best;" it's hardly a surprise that the Judge rules in favor of the government smashing the monopoly (the Judge's absolute faith in the people's votes ensuring the Constitution's validity will no doubt come off as a sick joke in today's America where that particular document is regarded with less than contempt).

Much of the humor in Judge Hardy's Children comes from Andy's efforts to fit into high society, with the folksy charm about the unsophisticated Hardys out of their element leading to satisfying pay-offs against the perceived "stuffed shirts." Rooney dancing the "Big Apple" is a wowzer highlight that apparently slayed the teens in the audience back then, and as I postulated before in my first volume review, I don't think it's much of a stretch to give Rooney credit for single-handedly planting the seeds of the behemoth media youth culture we now suffer today. Some of the plot machinations are uncharacteristically a bit clunky here; how can the Judge be blackmailed into delivering a verdict when the plot is already revealed in a gossip column? What about Aunt Milly, here played by Betty Ross Clarke, telling the Judge to throw Marion under the bus because she's young, rather than taking the fall himself to spare her (a very unHardy-like thing to suggest)? And how about scrupulously honest Judge Hardy lying to the public over the radio about how he supposedly set up the whole scam with Marion to trap the crooks? Would Judge Hardy ever think it was okay to lie in his public capacity, to cover one of kids' tracks? Doubtful.... Still, there are plenty of good moments here, particularly another familiar Hardy convention: Emily bucking up James when he believes everything is lost and that he'll have to start all over again--a daunting task at his age, and an anxiety no doubt familiar to many of those Depression-era ticket buyers. A transitional entry in the franchise before Rooney's irrepressible energy and mugging essentially hijacked the series.

LOVE FINDS ANDY HARDY

After Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone) sentences 12-year-old tractor thief Jimmy MacMahon (Gene Reynolds) to work on a farm, the judge personally intercedes in a debt collection case and in the process, niftily acquires a cook, Augusta (Marie Blake), for his wife, Emily (Fay Holden). Not so easily worked out is young Andy Hardy's (Mickey Rooney) latest scheme: buying a car. Short the last 8 bucks on a 20 dollar roadster, Andy is saved when friend Beezy (George Breakston) offers Andy a job: date his girl Cynthia (Lana Turner) until he gets back home from a Christmas vacation and he'll pay Andy the 8 bucks he needs. Newcomer Betsy Booth (Judy Garland), a poor little rich girl visiting next door to the Hardys, would gladly pay Andy the 8 dollars and more...if she thought she had a chance with the dashing older Andy. Problems arise, however, when Cynthia tires of Andy's safe dates and wants, um...more, while girl-next-door Polly (Ann Rutherford) complicates Andy's Christmas party plans by re-appearing in town. Top all that off with Emily being called away from Carvel when her mother suffers a stroke.Probably the most easily-recognizable title in the series, Love Finds Andy Hardy is also arguably the best representative of the franchise, perfectly capturing the breezy charm and innocent humor we often associate with these movies as a whole. Written by Vivien R. Bretherton and William Ludwig, Love Finds Andy Hardy's classic, elemental structure (Andy juggles three babes...four if you count the car) is crammed with one tight scene after another, propelling the consistently engaging, entertaining story along at an invigorating pace. Forget corrupt governments or local con artists or even Marion's eternal struggle for romantic happiness (she mentions dumping Wayne, and thankfully we hear no more of her "boring icks"), Love Finds Andy Hardy is all about Andy, girls and cars, achieving a lightness of touch that even Emily's off-screen deathbed vigil can't dampen. Marion's love life is pushed firmly into the background (Parker had to have seen the writing on the wall when the script called for her to pinch-hit for Fay Holden here), leaving almost the entire movie for Andy to scheme and plot to get his car, keep Polly, not hurt Betsy, and kiss Cynthia as much as possible.

The addition of Judy Garland to the mix is inspired (she would only appear two more times in the series); her sweet, vulnerable Betsy is not only a necessary softening agent to cocky little sh*t Andy's hijinks, but also a potent counterpoint to smoldering sex pot, Lana Turner, in her first appearance at M-G-M following her move, along with director Meryvn LeRoy, from Warner's. Judy sings three songs and breaks your heart, while Mickey believably imitates one of those Tex Avery animated wolves, complete with bugging eyeballs and tongue hanging out, anytime Lana simpers and pouts (it's a shame the series wasn't "big" enough to accommodate more often these two larger-than-life talents; Garland's sad-sack Betsy brings out a gentleness in the Andy character that's quite appealing). The writers even drag in a resourceful kid for the tykes at the matinees (future TV director Gene Reynolds), and make room for a humorously grumpy cook this time out (The Addams Family's Grandmother), helping to elevate the laugh quotient here. Perfectly constructed entertainment, expertly combining humor, song, romance, and melodrama, as only Mayer's M-G-M could.

THE HARDYS RIDE HIGH

After putting married spend-thrift Susan Bowen (Marsha Hunt) in her place for exceeding her household allowance ("Susan, you'll find that what a generous husband gives is a lot more than you're entitled to in a square deal," the Judge says with a knowing smile), Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone) is pole-axed by visitor Jonas Bronell (George Irving), a lawyer from Detroit. It seems that the judge, the great great grandson of the War of 1812's Colonel James Standish Leeds, has inherited $2 million dollars from the Leeds Automobile estate...if he can prove his legacy. With Polly Benedict (Ann Rutherford) next door entertaining swell Dick Bannersly (William Orr) and giving scruffy football hero Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney) guff about not being sophisticated, Andy's all for a trip to swanky Detroit (hee hee!) to become a millionaire. For that matter, so is Aunt Milly (Sara Haden), the Judge's spinster school teacher sister, who hates her dowdy small town image, and who wants to "cut loose" just once. Meanwhile, Philip Westcott (John King), the adopted son of the last, recently deceased Leeds, welcomes the Hardys to shiny, bustling, expensive Detroit (hee hee!). Despite his possibly losing the family fortune to blood relative Judge Hardy, he couldn't be a more obliging companion to young, impulsive Andy...and that's just what worries the Judge.

In this sixth entry in the Hardy series, signs of repetition are already beginning to show. After all, the plot of The Hardys Ride High is really nothing more than a thin reworking of Judge Hardy's Children, with Detroit subbing for Washington as the gee-whiz Hardys take in the sights, the Judge working out the probate of the Leeds will in place of working on the D.C. utilities commission, and Aunt Milly (of all people) stepping in for Marion's usual romantic tribulations, getting fooled by a real estate agent, instead of Marion getting duped by a Washington power couple. The notion of the Hardys somehow being "changed" by high society and money is carried over, as well (Emily, relieved when the money is no longer a factor says, "We wouldn't ever be the Hardy family with two million dollars."). Familiarity of situation and plotting certainly didn't matter with audiences at this point, though; they enjoyed that repeatable experience with the Hardys, with grosses going higher and higher with each entry. That kind of repetition, however, would soon turn into more rigid formula, and would ultimately work against the series' later entries.

All of that isn't to say that The Hardys Ride High isn't enjoyable--it certainly is. The movie's most unexpected element--the substitution of Aunt Milly into Marion's usual role of unfulfilled romance--is also its best. Haden, who mostly served as background filler in the series, finally gets her own subplot here, and it's quite touchingly done. Screenwriters Agnes Christine Johnston, Kay Van Riper, and William Ludwig give her a rather poignant scene with her brother, Judge Hardy, where her long-suppressed desires peep out momentarily: "James, I'm an old maid. I'm Aunt Milly Forrest, the schoolteacher. Why it'd turn this town upside-down if I even got a permanent wave," to which the Judge responds, rather obtusely, "Steady, Millie, steady. You've always been my good right arm," prompting Milly to sharply reply, "No woman wants to be a good right arm, except to her own husband. I don't want to teach school. I want to cut loose. I want to see things and do things before I get too old." Her quiet hurt when she discovers her Detroit businessman suitor is really just a real estate agent looking to make a sale, is beautifully handled by Haden; it's a pity the producers couldn't find more for her to do, more often. Equally unexpected is the sight of Judge James K. Hardy, pillar of moral fortitude, ready to burn the only surviving evidence that points to him not being a blood heir to the Leeds fortune--that's rather a shock for fans of the series to see the Judge almost tempted into doing something so unethical. Fun moments of course include Andy's efforts to appear sophisticated, from his initial reaction to being rich ("I'm gonna start insulting everyone I know!"), to his green-at-the-gills terror at being face-to-face with ready-for-sex party girl Virginia Grey (is he mad?). An entertaining entry in the series, to be sure...but the stitching and seams of the Hardy pattern make their first appearance here.

ANDY HARDY GETS SPRING FEVER

After suspending a man's sentence for kissing a girl in the local lover's lane (the Judge suddenly realizes it's spring), Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone) receives two visitors in his chambers: businessman James Willet (Stanley Andrews) and chemist Mark Hansen (Byron Foulger). The pair have astonishing news: the Judge's worthless aqueduct land has 8% boxide in it, and that means aluminum. Once the Judge confirms this analysis, he puts the land up for sale, with the two out-of-towners convincing him that he's the man to lead their aluminum mine corporation...with the help of some of the Judge's and his friend's capital. Meanwhile, Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney) discovers that next-door steady, Polly Benedict (Ann Rutherford), is very interested in handsome visiting Naval engineer, Ensign Copley (Robert Kent), who's in town to work on a nearby civic improvement project. Dejected, Andy goes to school and is knocked out by the sight of his drama teacher, Rose Meredith (Helen Gilbert), who, truth be told, seems a little knocked out by Andy, as well. Andy is in love, and he figures the best way to win Miss Meredith's heart is to write the school play: a reworking of Romeo and Juliet...with Polly sitting in as a little native girl, throwing herself into a volcano over unrequited love. Will Rose return Andy's love, and will the Judge avert personal and professional disaster when his mining concern turns out to be a scam?

The first Hardy entry not directed by series regular, George B. Seitz, Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever is frequently criticized by fans and even some of the cast for having a different tone than the other Hardy movies. Helmed by W.S. "One Take Woody" Van Dyke (classics such as the original Tarzan the Ape Man, Hide-Out, San Francisco, and The Thin Man), Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever is at times a little more morose, a little darker than the rest of the series in those scenes where Andy experiences the excruciating pains of early, impossible love...but for the most part, it plays not unlike the other offerings in the series (contrary to the critics, the Metro factory, just by its very physical set-up, wouldn't have allowed a product to go out that was markedly different than its preceding ones). None of the previous movies had Andy attempting to act so grown up--and suffering the inevitable disappointments that come with more mature romantic love--so perhaps that's why it unsettled those who expected more "woo woos!" from the usually peripatetic fireball Rooney. Then again...maybe the common perception of Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever as being "not as much fun" as earlier efforts is just a reflection of fans realizing that the series--and Andy/Rooney--are by this point noticeably aging. Perhaps they didn't like that thought: they didn't want their fantasy Carvel and idealized Andy, to mature.

Whether or not one cares for the overall dampening that those romantic scenes between Rooney and Gilbert put over the movie as a whole, you can't argue with the skill in which Metro orchestrates them. Executed with a quiet, moonlight romanticism that would be worthy of a Robert Taylor or Ronald Colman melodrama, Andy's love scenes with Gilbert, complete with Metro's gorgeous set decoration and evocative lighting, are palpably believable, thanks in no small part to Rooney and Gilbert. Rooney's performance here is probably the best one he delivered in the series, where he ably conveyed a choked, anguished desire for the unattainable Gilbert. As for Gilbert, it's a shame her career didn't amount to more (she seems to have been more famous for her six troubled marriages, rather than for any subsequent parts), because she's heartbreaking here, presenting a luminous, silent-screen profile and a melodious voice that believably devastates Rooney at first sight. Their scenes together are as delicately acted as they are scripted (series regular Kay Van Riper again), deftly mixing pathos and light humor. I would imagine fans of the series would have enjoyed more comedy scenes like the Judge getting spring fever over the idea of becoming rich, or Emily worrying over "my little man," or Polly delightfully teasing Andy with another suitor (I love it when she twists the knife the next day, sending him a note at school, teasingly saying, "Don't bother me,"), and I certainly wouldn't have minded more, either. However, considering how the series was already starting to repeat itself by this point (how could it not at three installments a year?), a change of pace, even a relatively somber one, isn't unwelcome.

THE COURTSHIP OF ANDY HARDY

Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone) has a dilly of a problem. Divorce respondents Roderick and Olivia Nesbit (Harvey Stephens and Frieda Inescort), through their acrimonious break-up, have caused great emotional harm to their shy, withdrawn, sensitive daughter Melodie (Donna Reed). The Judge may be able to force Roderick to pay support, and force Olivia to let Melodie visit her father...but what can he do for Melodie? Well, when his son and aspiring tow truck driver Andy (Mickey Rooney) gets in a tight spot with FBI Agent Stewart Dwight (Steve Cornell), when Andy is falsely accused of stealing the agent's car, the Judge has a plan: date Melodie and bring her out of her shell, and he'll see what he can do about squaring Andy's legal problems. Meanwhile, older sister Marion (Cecilia Parker) has her hands full with new boyfriend/jackass, Jefferson Willis (Willliam Lundigan), a rich-boy drunk who has an annoying P.A. loudspeaker in his car. Emily (Fay Holden) has legal trouble, too; she's ordered a full cutaway coat for James...but it comes C.O.D. for 20 bucks more than she agreed to, and the company wants payment now or they'll sue her in the Judge's court. Oh yeah...and Melodie is an ugly duckling, waiting to be a swan (...in case you hadn't already guessed that).

Outwardly busy, but in fact a slim, slight entry in the series, The Courtship of Andy Hardy has any number of fast-moving subplots that stick to the Hardy formula: the Judge taking personal action to deliver true justice in a case; Marion's usual romantic fumblings, this time with a drunk; Emily involved in a humorous domestic kerfuffle; and Andy's expected girl trouble. Taken individually, some work fine...while others miss the mark. This was the 12th entry in the series, following the depressing-at-times Life Begins for Andy Hardy, and so I wonder if a decision was made to lighten the tone of this next offering...particularly since it was shot and released during the first few bleak months of the war. It was too soon for even an oblique mention of the war in Carvel's mythical small town, so here Andy, of draftable age, is working at Duggan's garage to earn money to pay off his New York debts (incurred in the previous movie), before going off not on a troop ship, but to college. Rooney, that irrepressible carouser when the cameras were turned off (one of Hollywood's all-time champion hounds), looks every day of his 21 years here (and then some), so it's rather odd to see the movie start off with him leading a more adult life, only to have the mechanisms of the Hardy formula kick in and have Andy return, in everything but name only, to high school (those quasi-school dances he incongruously attends, with his high school friends in tow, and his helping a high schooler come out of her shell). While Rooney was still comfortably in the Quigley Top Ten Moneymaker poll for 1942 (but not number one any longer), it must have seemed clear to the Metro execs that the Hardy series was ready to, or had already, peaked. As well, Louis B. Mayer certainly wasn't happy that Rooney had married newcomer Ava Gardner (if that didn't make a man out of you, nothing would), with the mogul rightly concerned that such a public display of Rooney's other "real" life would conflict with his Andy Hardy image. So, it's understandable that Mayer would want Andy/Rooney to stay in Carvel and at home as long as humanly possible, with The Courtship of Andy Hardy a holding pattern for that doomed plan.

While we're prepared here to go along with Andy growing up, but not away, from Carvel and Mom and Dad, and while some of the tow truck shtick is pretty funny, that fuzzy subplot is completely dropped in favor of moving Andy back into one of his high school romances...only it's not really a romance at all (that whole FBI agent/stolen car subplot doesn't make sense, anyway; no wonder they just drop it for the rest of the movie, tying it up unconvincingly at the end). This Andy Hardy romance is about Andy acting like a creep, treating a pretty girl as if she were a leper, paying his friends to dance with her, getting her to fall in love with him, and then, when she blossoms into a stunningly gorgeous, compelling creature...he still doesn't really want her (Reed is lovely, as always, and perfectly cast here). Huh? The storyline doesn't show the Andy character in a good light at all (he's a real sawed-off user here), and no amount of last-minute redemption (he fixes her up with a love-sick friend) can save him. What does work are the sweet, funny scenes of folksy, nostalgic (and wonderfully idealized) Americana that dependably crop up in almost all of the Hardy movies, like newly-employeed Andy insisting on giving his mother room and board money, or Judge Hardy's father-to-son talk (where he admits to breaking rules as a youth, too...and paying for them), and Emily's crazy check-balancing bit. Those are the moments you remember from The Courtship of Andy Hardy; it's just a shame they weren't integrated into a storyline that actually paid off in the way we've come to expect from this usually precision-engineered series.

ANDY HARDY'S DOUBLE LIFE

In one week...Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney), America's favorite teenager, will leave his hometown of Carvel to travel to Wainwright College, where he'll major in law, just as his father, Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone), did when he was Wainwright's B.M.O.C. years before. Unfortunately, the Judge has decided he'd like to accompany Andy on his first day, showing him around campus, and introducing him to all the faculty--a notion that dismays Andy, who doesn't want the whole school to think he's a pantywaist. Before he leaves on Friday, Andy needs to have his spiffy New York City car sent back home, so he sells his zebra-stripped jalopy for 20 bucks to his friends, sending off an unsecured check to New York with his friends' assurances they'll cover it. Full of himself, and feeling like an adult, Andy asks his sister, Marion (Cecilia Parker), how to dump girl-next-door Polly Benedict (Ann Rutherford) so he can give her the "pleasure of waiting for him" to return from college four years later. Marion advises him to tell Polly he's given up his childish enthusiasm for girls, but Polly isn't buying it, and decides to teach him a lesson: she has visiting friend and college co-ed psych major Sheila Brooks (Esther Williams) tease Andy into a relationship to show up his lies about being A.W.O.L. ("A Wolf On the Loose"). Meanwhile, the Judge has to decide a tricky case involving little Tooky Stedman (Bobby Blake, from M-G-M's Our Gang series) breaking his arm while coasting down a street in his wagon (could he see a red flag on the lumber truck, or not?), while Andy has to negotiate a trickier rite of passage for a young man: how to tell his father he doesn't need to hold his little boy's hand anymore.

Even though there would be two more entries in the official Hardy series, following Andy Hardy's Double Life (not counting Rooney's 1958 attempt at a reboot), you could make a good case for this 13th installment being the last true Hardy picture. Just as the previous Courtship was a stop-gap measure to figure out how to continue the series when Rooney was getting older and the world war was looming large in the audience's mind, Andy Hardy's Double Life shows Andy not only leaving Carvel for college, but leaving behind his boyhood for good. He sheds his girl, he sheds his two cars (he gives the newer one to Marion, just as much out of love as necessity, since freshman can't have cars on campus), and he sheds the need for his father to always step in and fix his problems. Without any of that...what is left of "Andy Hardy?" It couldn't have been missed by ticket buyers who were seeing their own sons off to war in 1942, that Andy here is leaving for college--not a troop train. As much as the audience took Andy and the Hardy family to heart, and as much as they loved the nostalgia and the idealization of them and their mythical small town of Carvel (people back then were just as smart and aware as they are today; they knew how these movies differed from real life), there was little chance the series could have been sustained much longer considering the harsh realities for American families that were being documented each day in the newspapers and newsreels. Even Rooney, anxious to serve his country just like any other patriotic young man at the time, badgered studio boss Louis B. Mayer to let him quit the Hardy series and join up, something Mayer opposed all the way up until 1944's Andy Hardy's Blonde Trouble, when, after the 1943 hiatus, the series stopped again until 1946's final entry, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy...which showed Andy returning to Carvel as a mustered-out vet (true, Mayer probably waited until Rooney's career had peaked before acquiescing to his demands; Rooney fell out of the Quigley Top Ten in, you guessed it, 1944). With Andy Hardy growing older and growing away from his parents and the safe confines of Carvel, the premise of the series was finally played out. And since the entire raison d'etre for the series was a wonderfully innocent, idealized, and largely happy celebration of American small town life, where potentially dark problems were instantly cured with a bit of the Judge's wisdom and Andy's pluck, the series couldn't by its very nature change and expand, and reflect the post-WWII American experience. It was doomed, as is everything, by its own place in time.

Sociology aside, Andy Hardy's Double Life is only a fair example of the franchise, mixing expected--and as expected, well-done--bits that remind us of earlier, better entries in the series (the slapstick wheeling and dealing for Andy's jalopy), with sequences that either don't make sense (Marion is still with drunky Jeff?) or go nowhere (Andy's anti-climatic encounter with Polly's father). As for Andy's "double life," the movie seems to take particular pleasure in humiliating Andy for his duplicitous feelings for Williams and Rutherford--a strange thing to do when the series used to only gently chide his youthful, selfish, rambunctious sexuality...while making no bones that it approved of them heartily. Here, Andy is going to be punished for the quite normal pole-axing he (or any man) experiences when he first sees Esther Williams in that white halter-top bathing suit (Williams, incredibly sexy, is also quite skilled here, coming off as a sharp cookie who's more than a match for Andy's shenanigans), with the girls relishing his final mortification. When we've graduated from laughing and appreciating essentially innocent, red-blooded, all-American horndog Andy Hardy's girl trouble, to being encouraged to enjoy his calculated comeuppance--when Andy is no longer seen as a hero but as a heel--the series is over regardless of any outside reality threatening to break through the moviescreen fantasy.

ANDY HARDY'S BLONDE TROUBLE

On the train bound for Wainwright College, Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney), terrified about his reception at college, befriends Kay Wilson (Bonita Granville), who just happens to be one of the first co-eds to be admitted to W.U.. Andy is immediately smitten...until he sees ice cream blonde Lee Walker (Lee Wilde) wink at him. Bent on pursuing either cupcake, Andy is disheartened to see first Kay responding more positively to cultured Dr. M.J. Standish (Herbert Marshall), who is frequently amused by Andy's gauche behavior, and second to experience Lee's strange yo-yo behavior towards him. What Andy doesn't know is that Lee has a twin onboard, Lyn (Lyn Wilde), a twin who's far more conservative than the flirtatious Lee...and that's why horny Andy keeps getting his face slapped. Meanwhile, back at home, Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone), doesn't have any court cases because he's come down with a serious case of tonsillitis, which is being treated by Brooklyn-born Dr. Lee Wong Howe (Keye Luke, who seems to give a start to anyone who first sees him in 1944 Carvel). When money troubles begin to outweigh his romantic tribulations, Andy decides to throw in his beanie and quit school.

Tired, wheezy college comedy, largely divorced from the Hardy formula. By 1944, the Hardy movies were no longer S.R.O. with the teens who originally championed them back in the late 30s. They had either grown up and moved on to more mature stars like Bogart, Cooper, Grable, and, ominously for Metro, Universal's Abbott & Costello if they wanted laughs, or they were in the service...or dead. Rooney, too old at 24 to play a naive college freshman (bags under his eyes and that disconcerting split lower lip that keeps magically appearing and disappearing throughout the movies), and too publically divorced from Ava Gardner to pull off the role which audiences almost solely identified with him, has clearly lost the manic energy and edge he used to bring to the Hardy pictures, often sounding tired or even downright bored with his dialogue here. Splitting off Carvel and Andy's family into a separate, minor subplot doesn't work at all, with Lewis Stone enacting some sort of strange surrogate father role to Chinese-American doctor Keye Luke that plays less as required WWII propaganda for our then-ally, than it plays as bad "Number One" son comedy without the clever Chan lines (today's hair-trigger, P.C.-obsessed reviewers will no doubt pounce on the scenes where the Judge and Emily are startled by the appearance of an Asian in the midst of war-time Carvel...while conveniently forgetting to mention that he's immediately accepted by the Judge and his family as an equal, and indeed as the boss concerning the Judge's health care). We even get some strange attempt to fashion a younger female version of Andy in the guise of Beezy's sister, Katy (Jean Porter), which doesn't fit here at all. Meanwhile, back on the train (a sequence that takes forever in this bloated, almost two hour comedy) and at Wainwright, Rooney makes dismal, moony love to a glacial Granville (what happened to that wonderful Nancy Drew bounce?), while reenacting stale old "twins" sight gags that A & C did way better with Martha Raye (Marshall looks alternately bemused and mortified to have drifted into this now cheap-jack series). By the final fade-out, when Andy--once an irrepressible, hyper-sexualized wood sprite, now fully neutered by "mature," bourgeoisie love--archly and stiffly instructs ill girlfriend Kaye over the phone on how to take care of herself, the effect delivered isn't humorous, but instead a dull glumness that finally, sadly indicates that Andy Hardy has indeed grown up...which means we have absolutely no more interest in him, or his life.

LOVE LAUGHS AT ANDY HARDY

World War II is over, and returning veteran Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney) has been "separated" from the services--a term that instantly confuses his mother, Emily (Fay Holden), when she receives a telegram from her daughter, Marion, informing her of Andy's whereabout. Emily is convinced "her little man" is married, but her husband, Judge James K. Hardy (Lewis Stone), laughingly reassures her this isn't the case. However, Emily has come closer to the truth than she realized; when Andy comes home to Carvel, he informs his startled family that he plans on returning to Wainwright College and immediately marry Kay Wilson (Bonita Granville, from the previous Blonde Trouble). Andy indeed has grown up (he doesn't even need an allowance from old Dad); in fact, when he meets Carvel's new heartthrob, Isobel Gonzales (Lina Romay), he isn't remotely tempted to resort to his old horndog antics: he's emotionally committed to Kay. When Andy returns to Wainwright, however, he has to put his romance on hold as Kay mysteriously disappears to attend to a "personal matter." Meanwhile, Andy gets roped into being the committee chairman for the Frosh Dance. Since Kay is M.I.A., Andy is set-up with statuesque Amazon, Coffy Smith (Dorothy Ford), making for a humorous pair, as pint-sized Andy attempts to jitterbug with the kindly giant. No amount of jitterbugging, however, will take Andy's mind off marrying Kay...but remember the movie's title.

An awkward, unnecessary, unsuccessful attempt to keep a series going that had already ended in the audience's mind. Released a full two and half years after Andy Hardy's Blonde Trouble, Love Laughs at Andy Hardy might as well have been released twenty years later, considering the contextual gulf that separated it from its predecessors. Rooney, a real-life veteran, had long disappeared from the top box-office polls, suffering a more severe fate than many of his male co-stars who went off to war only to come back to uncertain Hollywood careers (guys like Gable and Taylor and Stewart may have stumbled out of the gate, but they recovered for decades-long careers as A-list leading men). Quite simply: due to the stunning success of the Hardy series, audiences really only wanted to remember Rooney as "Andy Hardy," and they wanted those memories to stay memories: they had little need for him to either reprise the role that he was obviously too old for (remember: aging the Andy character didn't help--the audience wanted the Andy character to stay forever young), nor to do much of anything else, for that matter (M-G-M's subsequent efforts to move Rooney back into the post-war groove with big pictures like Summer Holiday and Words and Music failed, and Rooney quickly found himself in low-profile Bs and supporting roles for the rest of his long, long career). As for Carvel and Andy after WWII, M-G-M was stuck between a rock and hard place; had they re-imagined Carvel and the Hardy family in the harsher post-WWII reality that audiences seemed to prefer in 1946, the tone clash would have been too great for fans of series. And had they tried to keep and protect Andy's adventures as relatively innocent and wholesome as they do here in Love Laughs at, the effect turned out to be tepid nostalgia, at best, and not at all compelling enough to continue. I would assume the few people that did come to Love Laughs at Andy Hardy did so out of curiosity, perhaps even a morbid one, to take a quick glimpse at an evocation of a time and place that no longer existed--an ironic endeavor, of course, since nothing like Carvel ever existed, anyway--one that may have had more to do with where they the ticket buyers once were...and where they stood in the vastly different 1946.

As for the movie itself...it's faux-bittersweet, in an off-handed way, but nobody wanted an Andy Hardy movie to be bittersweet, especially past the series' sell-by date, and they certainly didn't want to see him lose in love...unless maybe Polly was there to give him a teasing, restorative kiss. Andy in the audience's mind was always ascending, so when we see him come back from the war, out of sorts as an out-of-place, older frosh who loses his girl to Sergeant Preston's Richard Simmons, it considerably deflates our anticipatory pleasure. Some nice moments are dropped in throughout, such as the older Hardys waving patriotically to the troops as they drive through Carvel, only to see their son thrown out of a truck (Rooney's wordless look at mother Fay Holden is priceless), or the hilarious frosh dance where Andy tries to dance with behemoth Dorothy Ford. However, too much of Love Laughs at Andy Hardy seems exceedingly tired and rote (Andy locked out of his house in a woman's robe, the whole silly lingerie contest), or garish (every time Carmen Miranda knock off Romay is inexplicably dragged on camera), or ill-conceived (I can understand the moviemakers deciding Parker's Marion wasn't needed here, but why in the world wasn't Ann Rutherford brought back as Polly? How can Andy Hardy come home to the Carvel of his youth...if his best girl isn't there?). The tepid critical and public response to Love Laughs at Andy Hardy was just another indicator to those who still weren't listening at Metro, Hollywood's slowest-to-change studio, that the times which once supported the nostalgic Hardy series to an almost hysterical level, were now long gone.

ANDY HARDY COMES HOME

It's 1958, and Andy Hardy (Mickey Rooney), a successful lawyer with the Gordon Aircraft Company, has returned to his home town, Carvel, with a potential bonanza for the sleepy town: he's convinced his bosses that Carvel would be an ideal spot for a new electronics missile parts factory, and he's been given the go-ahead to negotiate a deal for the land. Reunited with mother Emily (Fay Holden), Aunt Milly (Sara Haden), sister Marion (Cecilia Parker), and her son, Jim (Johnny Weismuller, Jr.), Andy settles into his old bedroom, and surveys the 8x10 glossies of the girls from his past, and drifts back into old clips from the series his memories. Heading over to the town's local records, Andy's aided in his search for suitable land by honey Betty Wilson (Pat Cawley). Negotiating a fair deal with recent Carvel businessman Thomas Chandler (Vaughn Taylor), Andy happily informs his boss that the deal is done...or is it? When the papers are ready to be signed, Chandler holds up Andy for twice as much money, and tries to break Andy's ethical resolve by throwing in a bribe, but it's "no go" for the son of Judge James K. Hardy. Soon, when Chandler discovers that Andy has found more suitable acreage, on the cheap, from best friend Beezy (Joey Forman), Chandler begins a public campaign against Andy to discredit him.

The equivalent of a failed pilot for a sitcom version of the Hardy series. How Rooney convinced M-G-M (or the other way around) to try for this second go-around is subject to debate (Rooney says he approached Metro at the same time they were looking for a way to bring Hardy back...which I doubt), but there's no question that Andy Hardy Comes Home was a complete failure on release, both with politely dismissive critics and a disinterested public. So many elements here are flat-out wrong it's difficult to find anything right with it...except maybe just the sight of lovely Fay Holden and Sara Haden standing in the doorway of the original Hardy false front, smiling and happy (Ann Rutherford, a smart gal, wisely sidestepped Rooney's offer to come back, which included a first draft of the story that had Andy married to Polly). After that nostalgic moment, all bets are off for Andy Hardy Comes Home. How did Marion get a son, Jim? Where's the father (I'll bet we'd have had an answer if deceased Lewis Stone's character was still here)? If this is a family comedy about Andy coming back to Carvel, why wasn't his family brought along right from the start, to give us a chance to mirror the adventures we remember so well (it might have worked with Polly as his wife, coming in for an extended cameo, but here, Patricia Breslin has nothing to do)? Why the extended first act that establishes Andy alone in Carvel, the subject of unbelievably awed reactions of the hep teens who still somehow cherish his reputation (why not go for satire here, and have nobody remember him)? Why do the moviemakers tease us with some kind of potential romance with Andy and Betty, to the point of introducing a jealous boyfriend, and then drop it (a chance, maybe, to make the series more relevant)? Why do we need to see Andy trying to act like a hip kid, dancing in the malt shop and trading car lingo with the cool dudes, when it so obviously doesn't work (Rooney, looking a bit older than his 42 years, just isn't...cute anymore--even when he strenuously tries to be so)? And how are we supposed to root for family man Andy, if we get zero scenes of him being a father (did someone find out little Teddy wasn't the "natural" his father was, and his scenes were trimmed)? The scripters may ape one of the older Stone/Rooney "father-to-son" talks that were highlights of the earlier movies, but it doesn't play if we've previously only heard three words come out of little Teddy Rooney--the "talk" doesn't work if the kid isn't really a "character" but merely a prop.

The plot of Andy Hardy Comes Home, really a re-working, oddly, of the very first movie in the series, A Family Affair, could comfortably fit in a 25-minute sitcom (that silly sitcom music at the beginning of the movie, instead of that beloved Hardy swing theme, is yet another grating mistake). Here, it's stretched out uncomfortably into feature length, with a finale that's as unbelievable as it is wretchedly staged (director Howard Koch was a far better producer...). When the final shot includes Judge Andy Hardy on his father's bench, fading up to a portrait of Andy's own family and a title card, "To Be Continued," one's first thought is, "What are those people's names again?" before you grumble, "Oh no it won't." A particularly depressing waste of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity...for a project that was D.O.A. thirteen years before it was released.

The DVD:

The Video:

All the titles here are presented in fullscreen, 1.37:1 black and white transfers, while Andy Hardy Comes Home is presented in a sharp, clean, anamorphically enhanced 1.85:1 widescreen black and white transfer--nice. No restoration has been done on these titles, but for the most part, they're pretty good, with reasonably sharp images, nice blacks, certainly some contrast issues at times, and the expected screen imperfections.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English mono audio tracks are as expected: decent re-recording levels, some hiss detectable, squelchiness at times, and no subtitles or closed-captions available.

The Extras:

Original trailers for all titles except Love Laughs at Andy Hardy are included. On the Love Finds Andy Hardy disc, several extras from its original DVD release are ported over: an introduction with John Fricke and Ann Rutherford, a radio promo, and a cool Hardy Family Christmas trailer, where the cast thank their audience for their loyalty.

Final Thoughts:

Delightful when it was still young and fresh, and problematic and lazy as it aged, the Hardy series was a landmark development in the evolution of Hollywood's "golden age"...and a harbinger of darker times coming for the studio system. Essential viewing. Get Volume 1 from the Archive, and watch them in order. I'm highly, highly recommending The Andy Hardy Film Collection, Volume 2.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published movie and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||