| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Der Bomberpilot & Nel Regno di Napoli

The Munich-based imprint Edition filmmuseum, with its region-free DVD releases of hard-to-find art-film titles from around the world, is fast becoming a premier source for great, less-discovered work available, at long last, for home viewing. After having made available rare selections from Wilhelm and Birgit Hein and James Benning through previous, indispensable releases, the label has now compiled a two-disc set dedicated to New German Cinema outlier Werner Schroeter, a renegade's-renegade director who worked, by design, even further outside of the mainstream distribution/production system and conventional aesthetics than compatriots like Fassbinder and Wim Wenders. What we have in this mini-compilation is a focused, sharp representation of the gamut run by Schroeter's fevered vision, at once hyper-stylized in conception and raggedly breathless in execution: On the archly avant-garde, virtually non (or at least anti-) narrative end, there's 1970's Der Bomberpilot, while 1978's Nel Regno di Napoli (The Kingdom of Naples) is as close as Schroeter gets to telling a story in the way it's most commonly understood that movies do.

Der Bomberpilot does, in fact, have a "story" -- the postwar struggles of a trio of women who, under Hitler, had been a successful traveling musical-revue troupe of singers and dancers. Now, forced to live in ignobility and through a downward spiral of personal desperation and tragedy, the three women concoct a delusional, insane plan to make a revisionist, "feminist" return to the spotlight in the U.S. of A. But this story comes to us already warped into the disjunctive form of fragmented, mad delusion: Voice-overs from the women describe their situation and fill us in on the details as onscreen moments of breakdown, suicide attempts, fantasy, drudging reality, and shamed loss create a melange in which the line between the "real" story and what the women frantically imagine or project is permanently blurred and mutable. The post-synched soundtrack -- replete with the aforementioned voice-overs, obsessively repeated, shrilly sung tunes from the Reich, and barely-matched dialogue for the rare dramatic scene -- butts up against the images, which are in their turn confrontationally unpolished: grainy, hand-operated 16 mm takes of a luridly-colored, exaggerated pageant of snippets from the characters' real and dream lives -- for the most striking example, there's the daydream of Carla, former star turned humiliated, Heidi-attired bakery clerk, that she's being rowed regally, funereally down the Blue Danube -- for a parade of tattered, defiant symbolism, disturbing and discordant dreams presented for our interpretation. It's an extremely disorienting but enthralling experience, the poker-faced "amateur" aesthetic of Andy Warhol/Paul Morrissey or early John Waters used to convey the backwash of histrionic downfall and unspeakable guilt drowning postwar (West) Germany. It works remarkably, trenchantly well; one senses that, in Schroeter's view, this is exactly the treatment warranted by his country's dark past and confusedly fallen present, and he wields the tools of his medium in such a way as to elicit our hearty agreement.

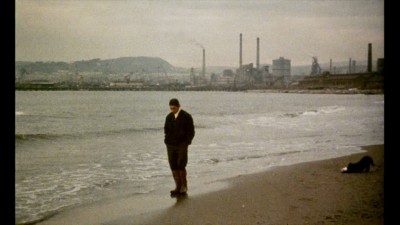

Nel Regno di Napoli, Schroeter's own voyage to Italy, has the appearance of something much more straightforward, hewing closely to a postwar timeline (actually marked and measured by emblematic intertitle cut-ins announcing the year, accompanied by radio bulletin-like narration updating us on the historical/social/political context) as it tells the story of little Vittoria (played as an adult by Cristina Donadino), born to a poor family in a rough neighborhood of Naples at the end of the war, whose fate, as she grows from impoverished girlhood to "success" as an airline stewardess in the 1970s, provides our dramatic compass through a living, clear-eyed history book, encompassing a whole microcosm of Neapolitan life in the turbulent, industrializing decades after the war: A brother, Massimo (Antonio Orlando) earnestly and diligently devoted to the promise of a better, fairer future for the oppressed workers held out by the Communist Party; a pretty, naïve, ill-fated French prostitute; the Spanish War veteran who becomes their local C.P. leader, and his wife, more pragmatic and lurking in the ideological gray area by buying rationed necessities on the ultra-capitalist black market; the turncoat bourgeois attorney who sells out his working-class neighbors for his tacky, impossible dreams of the good life; and the operatically evil heiress/factory boss lady (Ida Di Benedetto) whose clutches Massimo fights to neutralize, but whom Vittoria ultimately just wants to escape any ideologically-impure way she can. The handmade, spontaneous quality of Der Bomberpilot is still part of Schroeter's palette here, as is lurid, exaggerated pageantry, but those tactics are the judiciously-apportioned spice in a more aesthetically expansive, dramatically motivated/unified collage of images and sounds. Raw, immediate, apparently spontaneously-taken shots (redolent, if not due to Schroeter's heightened tone then because of the setting and the period, of Italy's most famous cinematic export, Neorealism) segue into movements and compositions striking in their deep, wordless conveyance of what it means to be a working-class postwar Neapolitan: In a gorgeous wide shot, the adult Massimo, destitute after imprisonment for his peaceable political activities, is tiny against a gray, sooty, imposing backdrop of factories and polluted sea; Vittoria and Massimo's very ill father, reduced to working at home as a struggling cobbler, is taken in by a smoothly traveling camera that moves slowly in on, then past him, through his window to the vast, timeless expanse of Mediterranean just outside his poor workshop. Nel Regno di Napoli is Neorealism and melodrama jarringly but effectively combined, placed in the service of historicizing and politicizing its riveting, saddening story. The individual experience within a class, the class's experience within a history -- the affecting, incontrovertible insistence that the personal is the political -- has rarely been achieved with such strange, eccentric, assured and enchanting verve as it is here.

These two films are only iceberg-tips, a small sampler of the places Schroeter's cinema is ready and able to take us. But, as carefully preserved and presented in this unexpected, treasurable edition, they're a beautiful introduction to the parallel cinematic universe conjured up by this intrepid rebel with a movie camera. It's a place where the most exquisitely stylized, self-conscious artifice and sophisticated intelligence coexist (if not peacefully then at least in a very fruitful, irresoluble dialectical seesaw) with the technically regressive, and primitive. It's like Wagner played "wrongly" but so very rightly as a self-aware, self-immolating punk-rock symphony, shards of incendiary cinematic glory bursting forth like sparks from Schroeter's willful, sublimely agitating induction of the friction between the beautiful illusion of the silver screen and the ugly, inescapable realities of a history, society, culture, and politics he, as a necessarily agonized, overwhelmed European (and, quite specifically, German) artist of the second half of the 20th century, knows all too well.

Note: These region-free/region-0 discs will not play on region 1-locked players, for example those manufactured for North America by Sony. Video:

These transfers of Der Bomberpilot and Nel Regno di Napoli preserve both the original aspect ratios of the films (1.33:1 for the former, 1.66:1/widescreen for the latter) and the rougher, rawer textures of the films themselves, which one senses were never "pristine" looking to begin with and appear with some signs of the immediacy and chaos of their making as well as, perhaps, some wear to the materials (with flicker and very rare scratches/debris to the frame), though never more than is easily excusable, or even sort of an authentic part of the underground-movie experience. One trusts that Edition filmmuseum has taken archival-level care in any restoration of the best materials available to them, and the films both look good and retain their character, with no compression artifacts (no aliasing, no edge enhancement/haloing that I could discern on close scrutiny) and certainly no overuse of digital smoothers to rob the image of its celluloid-like grain and vibrancy.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 track of each disc takes all due care with the films' original mono sound (in German with optional English or French subtitles), obviously presenting all dialogue and music with as much resonance, clarity, and depth/range as the carefully preserved soundtracks allow for. There are audio oddities in the films (the intentionally post-synced/mismatched soundtrack of Der Bomberpilot, or the self-consciously scratchy source music used in parts of The Kingdom of Naples), but there is never any distortion or imbalance that can be readily attributed to the transferring of the audio onto digital media.

--To Live and Die in Naples (87 min.), an audiovisual essay completed in 2010 by Gérard Courant, consisting on the sonic level of an audio interview conducted by Courant with Schroeter at Cannes in 1978 (where The Kingdom of Naples was being presented), and on the visual level of illustrations -- stills, clippings, photographs, text -- relevant to the discussion, which ranges from German cinema as a whole to Schroeter's influences and methods of working, from moment to moment. The visual elements are an okay touch, but this would have worked just as well as an audio-only bonus; regardless, it's an enlightening visit with the affable but brutally honest Schroeter and his complex, difficult processes of looking at the world and responding through his art.

--"Werner Schroeter at Osterreichischen Filmmuseum" (15 min.), a Q&A conducted between the audience and Schroeter at the podium after a 1978 Vienna screening, and captured on black-and-white video. Again, it's interesting and revealing to see the director in action, describing (without "explaining") his film and his intentions for it to the sometimes obviously baffled spectators, who may still leave no less baffled, but with more rich food for thought.

--A selection of stills from the shooting of The Kingdom of Naples.

--A trilingual illustrated booklet with essays on Schroeter, a nice-looking, well-designed affair whose only drawback is the fact that the essays in different languages are not translated into the others; if you read English but not German or French, you get a (well-informed and well-written) 2012 magazine piece by Bradford Nordeen about a MOMA Schroeter retrospective that year, but not the essay in German by Fassbinder about his filmmaking comrade-in-arms, or Gérard Courant's 1982 piece for a Cinémathèque Française publication.

Two strange, indeed bizarre, utterly disturbing and intoxicating works from the far ends of the spectrum of German filmmaker Werner Schroeter's filmography, 1970's experimental/avant-garde Der Bomberpilot and 1978's nominally narrative/dramatic Nel Regno di Napoli (The Kingdom of Naples) are essential additions to the DVD libraries of any and all New German Cinema (Wenders, Fassbinder, Schlondorff) aficionados. Not that Schroeter is any more easily categorizable than his compatriots in that movement (more united by their moment and by economic/production conditions and means than aesthetically, at any rate); as these two films -- for all their differences both equally drenched flamboyantly in the underground, homemade, labor-of-love spirit of an inveterate outsider/independent artist -- richly attest, Schroeter could never "fit" easily into anything, whether it's a movement or a new wave or the history of cinema itself. What he does share with his fellow practitioners of New German Cinema -- a lingering, tortuous post-Hitler trauma and an impatience verging on disgust with postwar West Germany's moribund, denial-prone culture and society -- manifests itself with such an original urgency here, whether through the lushly, poisonously overripe fantasy-parable of Der Bomberpilot or the eccentrically but pointedly historicizing, melodramatic-Neorealist maneuvers of The Kingdom of Naples, that they easily smash through any ready-made molds to abrasively dazzle our eyes and insistently blow our minds. Thanks to Edition filmmuseum's restorative/curatorial efforts, these too-long inaccessible portals into Schroeter's ultra-stylized yet deeply visceral vision are now readily available to all, a new, wholly unexpected cinephilic adventure that for those (like yours truly) who hadn't yet been initiated into the cult of Schroeter, will make an indelible mark and leave you hungry for more. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||