| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Tarzan - The Complete Second Season

Warner Archive all but exhausts their vast holdings of Tarzan movies and TV shows with the release of Tarzan - The Complete Second Season (1967-68). Other than Tarzan, the Ape Man (1959), MGM's terrible remake of the Johnny Weissmuller classic, Warner Home Video seems to have finished off the "official" Tarzan films series (1932-68) and TV series (1966-68), leaving only a few footnote-like stragglers, such as the faux theatrical features actually derived from episodes of the TV series starring Ron Ely as the Lord of the Apes.

The TV series isn't bad at all, though in fashioning a more realistic and family-friendly Tarzan it perhaps unwisely eschewed elements from the Edgar Rice Burroughs novels and recent Sy Weintraub-produced Tarzan movies of the late-1950s and ‘60s that might have helped. The Tarzan of the Ron Ely television series lacks the mythical, majestic qualities present in the best Tarzan adaptations, and the series probably could have benefited had its scripts incorporated fantasy elements that might have created a sense of wonder the series profoundly lacks. Instead, the TV Tarzan, while quite good in other respects, is weighed down by standard jungle adventure plots, a limited genre, especially for a weekly series.

Warner Archive released the first season of Tarzan across two volumes in April 2012. The Complete Second Season dispenses with that, culling all 26 one-hour episodes into a compact six-disc set in a standard DVD-size case. Actor Ron Ely is still around and it's a shame he wasn't invited to do an interview or episode introductions, which might have enhanced what amounts to a bare-bones release.

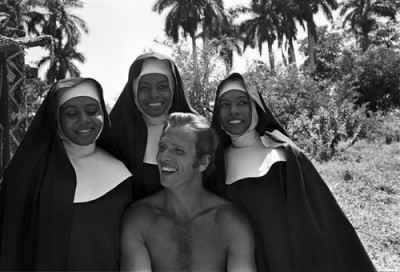

Sister Act: Tarzan Meets The Supremes

As before, a bit of history is in order: The Tarzan film series appeared to have run its course by the mid-1960s, when Tarzan the television series made its 1966 debut. The official film series got off to a good start in 1932, with Tarzan the Ape Man, famously starring Johnny Weissmuller, five-time Olympic Gold Medal-winning swimmer. The next film, Tarzan and His Mate (1934), remains a pre-Code masterpiece, a picture as exciting, innovative, violent, and sexually explicit (more so in the latter case) as the contemporaneous but more widely remembered King Kong (1933). The third film, Tarzan Escapes (1936), might have been its equal, but that one was heavily edited and reworked after audiences found much of it too intensely horrifying.*

After that, MGM wholesomeness quickly seeped in, seriously undercutting what had come before, particularly in Tarzan Finds a Son! (1939) and Tarzan's New York Adventure (1941). Tarzan's Secret Treasure (released earlier in 1941) is somewhat better, and might have been great had the original ending, in which Tarzan's love Jane (Maureen O'Sullivan) was to have tragically died, been retained. (Weissmuller's moving performance for this scene was basically retained, however.)

While no great actor, Weissmuller nonetheless was a great Tarzan. His was a monosyllabic character with a deep distrust, usually justified, of "civilized" man. He was uncompromising and unhesitatingly violent when he needed to be, but he treasured his freedom and his animal friends, while Jane, with whom he had the most overtly sexual relationship among 1930s and '40s Hollywood characters, further humanized him. (O'Sullivan's Jane was cultured but sexy, at least at first, while Brenda Joyce's equally fine Jane in the later films was intuitive and sensitive yet assertive toward her common- [jungle-] law husband.)

From here Weissmuller and Tarzan moved over to RKO, in films considered slightly inferior, but which this reviewer vastly prefers to the later MGM ones. Like other Hollywood stars, Tarzan fought Nazis for a couple of years, but then returned to more traditional, sometimes fantasy-laced adventures. As with the first two MGMs, the RKO Tarzans had moments bordering on poetry. In one film, ruthless hunters across the river from Tarzan's territory insist they have a right to slaughter as many animals as they damn well feel like. Tarzan responds with his classic jungle cry - and all of the endangered animals diligently cross the river en masse into Tarzan's domain, and safety.

Director Kurt Neumann brought a lot of style to these later Weissmullers, which were all pretty good until the last one, Tarzan and the Mermaids (1948), at which point Weissmuller hung up his loincloth and became African hunter Jungle Jim for Monogram, basically Tarzan with his clothes on.**

Lex Barker replaced him for the next five movies, from Tarzan's Magic Fountain (1949) through Tarzan and the She-Devil (1953). He was more conventionally handsome yet somehow regal, a fine Tarzan overall, and in some respects more like the Tarzan of author Edgar Rice Burroughs's novels, but he lacked Weissmuller's unspoiled innocence. The series, still at RKO, was generally good, though dipping slightly if steadily throughout the Barker years.

Next came bodybuilder Gordon Scott, who debuted in Tarzan's Hidden Jungle (1955) alongside future wife Vera Miles. The Gordon Scott Tarzan films were far and away the most schizophrenic. Tarzan's Hidden Jungle was much like Barker's later, cheaper ones, but the next movie, Tarzan and the Lost Safari (1957), was not only the first in color, it also was the first to be shot in England with a mostly British cast, and it featured fairly extensive second unit footage filmed in Africa.

However, the next film, Tarzan's Fight for Life (1958), made back in Hollywood, was incredibly cheap and stillborn, shot almost entirely on phony soundstage "jungle" sets. In these same spartan surroundings Scott also starred as Tarzan in an even worse unsold television pilot eventually released to television as Tarzan and the Trappers.

But then, something happened that changed the entire course of the franchise. Rights to the series were acquired by producer Sy Weintraub, and a half-century before the term "reboot" defined a completely revamped continuing film series, Weintraub did just that. Though Gordon Scott continued in the role of Tarzan, he was suddenly an educated, cultured and grimmer ape-man closer to Burroughs's original, and not limited to "Me Tarzan. You Jane" type dialog. Further, Tarzan's Greatest Adventure (1959) was filmed almost entirely on location in Kenya, and featured two formidable actors playing the villains: Anthony Quayle and relative newcomer Sean Connery. It was easily the best Tarzan movie since Tarzan and His Mate (1934).

After that Scott made just one more, Tarzan the Magnificent (1960), but that was nearly as good and featured stuntman and actor Jock Mahoney as an equally vile, memorable villain. However, as popular as Scott was and as good as his last two entries were, Scott himself was a limited actor and for all his muscles had a boyish face not really suited to more adult, darker Tarzan envisioned by Weintraub. When Mahoney took over the part for Tarzan Goes to India (1962) that actor was already 42 years old, the oldest rookie Tarzan ever. Further, while athletic he was lanky and a startling contrast to Scott, his leanness stretched further by illness while on location, where he lost even more weight.

But Mahoney proved the best Tarzan since Weissmuller, and so different that comparisons are pointless. His was a more world-weary, experienced Tarzan than Scott's, instead more like the John Wayne of She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, or the outcast Wayne played in The Searchers. Mahoney's two Tarzans, Tarzan Goes to India and Tarzan's Three Challenges are superb. Featuring spectacular, almost other-worldly locations (in India and Thailand), large-scale action set pieces, and rich, sometimes even unexpectedly moving characterizations, they represent the post-Weissmuller Tarzan series at its peak, even over the more widely acclaimed Tarzan's Greatest Adventure. Although they've been released to DVD via Warner Archive's MOD program, they're really ripe for rediscovery and a Criterion Collection-type remastering loaded with extra features.

After nearly dying while making Three Challenges, Mahoney left the role and was replaced by Mike Henry for the last three Tarzan movies. Tarzan and the Valley of Gold (1966) is quite good, furthering the series' James Bond-like stylings, which dated back to the pre-Bond Greatest Adventure. Like the two Mahoneys, it used its location, this time Mexico and its Teotihuacan ruins, to excellent advantage. However, Tarzan and the Great River (1967) and Tarzan and the Jungle Boy (1968), filmed back-to-back in Mexico and Brazil, and in an unwise move released during the TV series' run, were fair at best and Henry soured on the role after he was bitten in the chin by the (much too adult) chimpanzee playing Cheeta.

And so Weintraub moved Tarzan to TV. Ron Ely became the latest in the long line of Tarzans. Like Mahoney, Ely was lithe and less muscular than either Scott or Henry, and he was much younger (just 28) with handsome, sculpted, even Romanesque facial features.

Clearly, Weintraub wanted to retain as many of the same qualities of his feature films for the series, but was up against impossible odds in terms of time and money. Unusual for a prime-time network (NBC) show, it began shooting entirely on location in Brazil, flying guest stars all the way to South America. However, the logistics proved impossible and the unit relocated to Mexico. All of season two was filmed there.

Nevertheless, the show succeeded in retaining its movie look to a point, offering viewers scenery not limited to what was driving distance from Los Angeles. Weintraub does resort to scads of stock footage from his earlier Tarzan movies, but this is not too intrusive, and some of the second unit and stock shots are used effectively, especially during the opening titles. Initially these begin with an incredibly impressive backward tracking shot of a charging African elephant, an image similar to the famous Tyrannosaur chase in Jurassic Park. The music accompanying this was likewise highly evocative, but that opening was replaced nine episodes in with much less interesting, more conventional opening titles.

To his credit, Ely, like other Tarzans before him, was fully committed. He insisted on doing most of his own stunts, and mercilessly abused his body in the process. During the first season alone he broke his nose, dislocated his jaw, separated one shoulder and broke another, broke ribs, pulled a hamstring muscle, sprained both ankles and was bitten in the head by a lion, requiring seven stitches. Some of these injuries were caught on camera (notably Ely's fall from a swinging vine) and retained for use on the TV show.

Appropriately there's no Jane domesticating this Tarzan (as television Standards & Practices would have insisted upon), nor is Cheeta the all-purpose cutaway/comedy relief of all the '30s through '50s films. Instead, for most shows excellent child actor Manuel Padilla, Jr. (American Graffiti), who co-starred in the final two Mike Henry films, appears as Jai, whom Tarzan sort of adopts, but who roams the jungle pretty much on his own, unsupervised.

Unfortunately, Tarzan the series follows the well-worn path of convetional jungle stories, opting mostly for conventional, not very interesting plots, and it tends to confine the action to generic locations where nothing is more than a few vine-swinging minutes away. There's not much in the way of quest or search-type stories like some of the better movies, nor are there explicitly fantastical scripts.

Episode titles indicate this general lack of imagination: "Tiger, Tiger," "Voice of the Elephant," "The Pride of a Lioness," "Jai's Amnesia," etc.

Nonetheless, the series attracted a much higher caliber of guest stars than the usual hour action-drama, actors who generally avoided episodic television or who at least were highly selective. This season set includes, among others, James Whitmore, Yaphett Kotto, Sam Jaffe, Brock Peters, mother and son Helen Hayes and James MacArthur, Ethel Merman, James Earl Jones, the Supremes (Diana Ross, Cindy Birdsong and Mary Wilson), Maurice Evans, and Julie Harris. That's a pretty distinguished line-up, and on top of more conventional but still welcome guest stars including Anne Jeffreys, Oscar Beregi, Michael Pate, Murray Matheson, John Doucette, George Kennedy, Lloyd Haynes, William Marshall, BarBara Luna, Simon Oakland, Diana Hyland, Antoinette Bower, John McLiam, Harry Townes, Strother Martin, John Anderson, John Dehner, Clarence Williams III, Karl Swenson, Malachi Throne, Raymond St. Jacques, Robert J. Wilke, Robert Loggia, Morgan Woodward, Michael Ansara, Henry Jones, Woody Strode, Chill Wills, Ted Cassidy, Fernando Lamas, Booth Colman, John Vernon, Nehemiah Persoff, and Neville Brand.

Video & Audio

Tarzan looks quite good, considering. The episodes source what appear to be old transfers but are reasonably bright and sharp, with good color and contrast, though they show a lot of damage and dirt, some inherent due to the mixing and matching of stock shots. It should also be noted that the review copy sent to us was a pressed DVD, and not a DVD-R. The mono audio is okay, and the discs are region-free, unlike MGM's MOD titles. No Extra Features.

Parting Thoughts

For Tarzan fans that, like this reviewer, enjoyed catching up with the film series chronologically on DVD and later as Warner Archive releases, the TV Tarzan is a welcome release. Recommended.

* Reader (and Tarzan authority) Sergei Hasenecz notes, "Horrifying, perhaps, but the full story of Tarzan Escapes is complicated. Oddly enough, the Hays Office made no request for cuts of the legendary and infamous Devil Bat sequence. Supposedly the reaction at previews caused MGM to self-censor their movie, although, again oddly, nothing shows up in the press at the time about horrified mothers and terrified children. Ron Hall writes at length about Tarzan Escapes in ERBzine, the online magazine dedicated to Edgar Rice Burroughs and his creations here. Hall claims to have seen an uncensored re-release print in 1954."

** More from Sergei: "This is the usual (and unimaginative) way Weissmuller's Jungle Jim is described, but there are significant differences between the two characters. First, except for his companion chimp, Jim has no control over the animals he protects. To get a herd of elephants to cross a river, Jim couldn't simply give a command. He'd have to stage a pachyderm rodeo (if he'd have had the budget to do it). Second, and perhaps more importantly, Jim has none of Tarzan's sexuality. Even with the latter 'domesticated' Tarzan movies, you knew why Jane was hanging around 'that bally jungle' (as Lord Greystoke's cousin once put it), and it wasn't unusual for Tarzan and Jane to still discreetly slip off together. Lastly, because he had his clothes on, one knew Jim was not a feral man, not an ape man. He was civilized, even if he lived in the jungle. He was an outsider who came in, no matter how well versed he was in the ways of the jungle. Tarzan was born to the life. The difference between Tarzan and Jungle Jim is the difference between a demi-god and a mortal."

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian and publisher-editor of World Cinema Paradise. His credits include film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||