| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Dr. Kildare: The Complete Second Season, Parts One and Two (Warner Archive Collection)

"Are you sick or something?"

"No, but I could be...if you took my case."

How can I concentrate on dying, Doctor...when you're so dazzling? Warner Bros.' Archive Collection of hard-to-find library and cult titles has released Dr. Kildare: The Complete Second Season, Parts One and Two, a 2-volume, 9-disc, 34-episode collection of the smash-hit NBC medical drama's 1962-1963 sophomore season. Based on all those fondly-remembered M-G-M medico-dramas with Lew Ayres and Lionel Barrymore, here updated for TV viewers with newcomer Richard Chamberlain and old pro Raymond Massey, Dr. Kildare was dismissed by quite a few so-called "serious" TV critics (there are no such things...) as glossy, inconsequential soap opera, and no more. However, "soap" never got in the way of good drama, with this second season of the highly-rated anthology sporting a clear majority of beautifully written, expertly produced, and socko-acted entries--yet another "lost" example of superior vintage television. No extras for these pristine black and white (with one color exception!) fullscreen transfers.

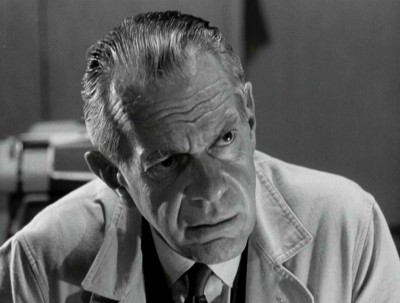

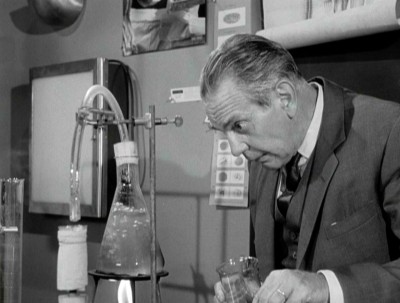

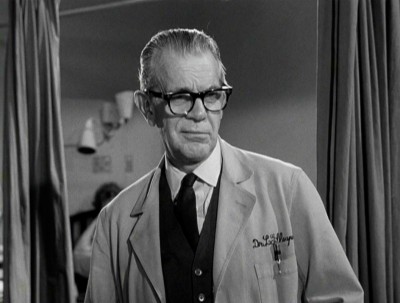

Mammoth, bustling Blair General Hospital. At the center of this modern metropolitan citadel of healing sits Dr. Leonard Gillespie (Raymond Massey), Chief of Staff at Blair. Brilliant, demanding, and fearsomely intimidating to those who only see the surface, Gillespie also possesses the wisdom of the just and kind--a tool of the heart that is as formidable as his scientific abilities, and one that he uses quite often with young Dr. James Kildare (Richard Chamberlain). Kildare, an intern at Blair, shows all the signs of becoming the most skilled internist Gillespie has ever taught...that is, if eager, impetuous young Kildare can avoid the myriad pitfalls that can waylay any young doctor who cares too much. Kildare isn't the only intern on Blair's staff; from week to week one might see Drs. Simon Agurski, Yates Atkinson, Thomas Gerson, John Kapish, and John Grant (Eddie Ryder, James T. Callahan, Jud Taylor, Ken Berry, and Bill Bixby), but their often flip attitude and casual job involvement is in sharp contrast to Kildare's almost holy dedication to the science of medicine. Good thing, too, because the varieties, complexities, and severities of the illnesses that wind up at Blair, and specifically when Kildare is attending, are staggering.

When Dr. Kildare premiered on NBC back in 1961, its production studio, M-G-M, was still a relatively minor player among the Hollywood movie studios getting rich quick by providing original programming to the television networks. So naturally, when it was looking to make inroads on the "Big Three"'s airwaves, Metro did just what pioneering Warner Bros. did in the mid-1950s to play it safe: Metro went back to their library and looked for once-popular titles that could be easily adapted for television. One such property that seemed a natural was M-G-M's old Dr. Kildare and Dr. Gillespie series of "B" medico-mysteries dramas, with Lew Ayres and Lionel Barrymore, which were now proving just as popular in televised reruns as they had been in movie theaters in the 1930s and 40s (you can read my review of the Lew Ayres-starring Kildares here). Tweaking the formula a bit, the new TV Kildare would find the once wheelchair-bound Dr. Gillespie now ambulatory, with whining, screaming Dr. Gillespie's penchant for playing rather sadistic head-games with young Kildare being eliminated. This small-screen Gillespie, embodied by imposing theater great, Raymond Massey, would now be mellifluously stern and exact...yet never deliberately cruel to almost surrogate son, Kildare. The Kildare character, forever learning the ropes of not only the technical but emotional side of medicine, would remain relatively the same: highly skilled, somewhat naive, earnest, and kind-hearted

The only major difference would be a reduction in the more direct line of mentoring and accountability that Kildare faced with Gillespie in the movies. On the big screen, young Kildare was Gillespie's personal pet assistant, who frequently worked outside the normal career progression of the other lowly interns. Here in the television Kildare, young Dr. James Kildare is just another intern. Of course Gillespie sees greatness in Kildare, but Kildare will have to work his way through the system like everyone else...nor will this Gillespie pull any outrageous stunts, as the movie Gillespie would often do, to save Kildare should he fail (having the TV Kildare go from ward to ward not only provides a variety of new cases each week--from psychotic children to drunken old bums to beautiful women with various fatal diseases--it also frees up Kildare to chafe and rebel against other established doctors and residents, leaving Gillespie as a watchful ally). After William Shatner and James Franciscus both declined the part, relative unknown Richard Chamberlain was picked over dozens of other young hopefuls for the role (Chamberlain--who sounds like a pretty interesting guy in real life--surprisingly doesn't provide a lot of detail on this or other aspects of the show in his fascinating autobiography, Shattered Love). When Dr. Kildare premiered in the fall of 1961, along with another new medico series on ABC--the somewhat grittier Ben Casey, with Chamberlain's DNA opposite, burly, hairy Vince Edwards--Chamberlain became a huge star (and despite his own self-criticism, a fine, natural performer prior to his later, more intensive acting training), as the two series started a mini-craze for the then little-seen-on-TV medical drama (Dr. Kildare and Ben Casey weren't the first medical dramas on TV--1951's City Hospital, 1952's The Doctor, and particularly 1954's Medic, with Richard Boone, held those honors--they were just the first ones to crossover into major mainstream popularity).

What's ironic about the now-relatively unknown television version of Dr. Kildare is that its lack of visibility on the small screen today is the opposite of the situation that helped get the series originally green-lighted in the first place: the popularity on the tube of the old, re-run Dr. Kildare movies in the 1950s. No doubt there was a decided reluctance in the pre-cable television syndication markets of the 1970s and 80s to book old hour-long black and white dramas, so it's not surprising that NBC's Dr. Kildare, a huge hit in the Nielsen's during most of its 1961-1965 run (it finished 11th overall for this second season), didn't subsequently acquire more substantial name recognition outside its original group of viewers (as opposed to, for example, half-hour color sitcoms, like The Brady Bunch and Gilligan's Island, which seemingly will play forever). Add to that lack of visibility Dr. Kildare's reputation by quite a few critics and historians as merely a glossy "soap" (as opposed to a "serious" drama), and that's why I call Dr. Kildare a "lost" show: up until its reappearance on DVD, it was difficult for general audiences to check it out...in order to see how those trivializing critics were wrong. And of course, these kinds of errors of critical assessment are compounded over time, because so many new writers about television history don't actually go back to the original source material; they simply parrot back what their (hilariously) self-important "pop culture" professors told them in college...which usually consists of a highly-generalized timeline that states "good" vintage TV began with live dramas and news shows, while dismissing and belittling anything popular or mainstream that subsequently came along that wasn't sufficiently subversive or revisionist or "edgy." Much like when I reviewed the often-maligned-but-excellent Peyton Place a few years ago (shame on Shout! Factory for discontinuing the DVDs of that fine series...), Dr. Kildare, at least in this second season, routinely delivers up one thought-provoking episode after another, sensitively written (with actual beginnings, middles and ends to the stories, where you experience something positive and life-affirming after watching them), directed by some of the best people in television at the time, and beautifully acted by top actors of the day. If that's a "soap opera"...then by all means, let's have more of these forgotten, dismissed soaps released on DVD.

The season opener, Gravida One, scripted by E. Jack Neuman and directed by Elliot Silverstein (still going strong at 87...), sets the mood and pace for the rest of the season, as a busy couple of days at Blair bring death...and life (the bustle created with the little 10-second "micro-stories" in the hallways, coming and going without context or resolution, gives this episode a thoroughly modern feel). There's a nice bit of contrast between Gillespie's acceptance of an old friend suddenly and inexplicably dying after surgery, and a devastated Kildare losing a 17-year-old girl to preeclampsia in O.B....while sardonic wise-ass Patricia Barry doesn't want to keep her baby (Dr. Kildare must have had tobacco sponsorship; everyone is lighting up here...even the pregnant mothers). The Burning Sky, as Warner Bros. helpfully points out in a pre-episode title card, was the only time Dr. Kildare was filmed in color, for a special one-week NBC promotion of their color programming. As cool as it looks in its saturated color, though, quite frankly, the show works better in black and white (even though color would definitely have helped in later syndication). An outdoor entry (to leave behind all that pea green at the hospital, no doubt), Chamberlain looks like he's having fun sneering with disgust at pompous, candy-assed Robert Redford, who's a whiz with medical facts, but a chickensh*t when the blood pours (looking at plump-faced Redford here, it's hard to discern any potential for iconic sex symbol-dom on his horizon). Another future superstar, Carroll O'Connor, has one of his many thankless pre-All in the Family roles here as a firefighter. Scripter Frank R. Pierce and director Paul Wendkos come up with a complex winner in The Visitors, an even-handed look at what happens when a Communist oil prince comes to Blair for treatment. The dialogue is thoughtful (ultimately, the Commies get no pass here), but it's a stretch buying John Cassavettes' overwrought performance. Theodore Bikel, never one of my favorites, is even more broad and unconvincing as a crummy Commie quack, but veteran character John Anderson scores, as usual, as a handicapped Korean war vet. Unfortunately, The Mask Makers, with Carolyn Jones turning into a bitter, revenge-seeking, wasp-tongued temptress the minute she has her nose bobbed, is a relatively shallow exercise compared to other episodes this season, with normally whiny Mike Kellin about the best thing here, as a concerned intern.

Guest Appearance sports a nice, uncomfortable turn by stand-up comedian Jack Carter as an egomaniac TV talk show host bent on destroying Kildare when Carter's son unexpected dies after treatment from the young doctor. There's kind of a low-grade A Face in the Crowd feel to this one, with an intriguing, well-written subplot concerning Carter's wronged, right-hand woman, Georgann Johnson (who's excellent). Gillespie sums up the feeling that used to be common in formerly responsible America, when he rips into legally vindictive Carter: "I can not sympathize with an undeveloped personality which tells itself, 'Because I have been hurt, somebody else must be at fault, somebody else must suffer with me.'" Beautiful. Hastings' Farewell is a devastating outing from Peggy and Lou Shaw, directed by Ralph Sevensky. Harry Guardino (who knew he could be this good?) suffers from aphasia...and loving wife Beverly Garland has had enough: she can't cope with him anymore and is ready to put him in an institution. It's up to Kildare, racing against the clock, to work with Guardino and prove to everyone that his mind isn't gone (Gillespie offers, "In medicine, there is no such word as, 'hopeless,'"). The use of home movies showing a pre-head injured Guardino is effective, as is the terrifying explanation of what aphasia patients actually experience. Breakdown sports an equally compelling turn from Larry Parks as a suspicious, jealous older resident bent on destroying Kildare, whom he thinks is showing him up. Director Lawrence Dobkin, working from Betty Andrew's suspenseful script, gets a remarkable performance out of Parks, with those black marble eyes of his peering with bright psychosis. Memorable. Whenever I hear a racist complaint about a White actor playing an ethnic character in one of these older outings, I always wonder why the quality of the performance is mentioned second (if at all). I don't have a problem with Law & Order's Steven Hill playing an Indian doctor in brownface--I have a problem with Law & Order's Steven Hill playing an Indian doctor in brownface poorly, as he does in the otherwise fine The Cobweb Chain, an intriguing look at the cultural differences that impact him as he works in an American hospital (Hill's attempt at Eurasian stoicism is badly misjudged).

Director Elliott Silverstein, working from George Eckstein's tough script, is back with a winner in The Soul Killer, a nervy, tense little number when ex-junkie Eileen Heckart gets current junkie Suzanne Pleshette's number from minute one. Lots of twists and turns in this one (including a rather suspenseful climax you don't see coming), with Heckart and Pleshette (beautiful, as always, and so underrated as an actress) scoring big with their complicated turns. It's hilarious to see the normally staid Massey laugh in this one (watch him try hard not to blow a scene, stifling a laugh caused by the marvelous Cheerio Meredith as a mouthy cleaning woman), as well as execute a 2-second twist at a "ribald" intern party for married Bill Bixby and--I'm feeling faint...--Barbara Parkins. Young Dr. Kildare goes home (just like he did in the old movies) in the gripping An Ancient Office, from scripter Theodore Apstein and director Don Medford. The perils of utilizing local coroners who possess no medical training (quite common, I believe, back then) is highlighted here, when Ed Begley, faced with a crib death, gives an off-the-cuff, incorrect verdict that causes the mother to attempt suicide. In the dense script, Begley faces reelection, and he's not above trying to buy his way out of admitting he's wrong...when he tries to bribe the grieving father with a job (corruption in Dr. Jimmy's hometown!?). As always with that great actor, Begley is remarkable essaying a character who goes from reassuring and folksy, to suspicious and angry and manipulative, to beaten and apologetic (this will be the only appearance of Henderson Forsythe and Irene Hervey as Jimmy's parents, Dr. Stephen and Martha Kildare). One of the season's best. The Legacy has young Dr. Kildare going to court where he has to choose between telling the truth in a liability case (and thereby denying widow Olympia Dukakis an insurance payout), or lying for her and her immigrant son. Gillespie and Kildare have a nice discussion about the state of truth in today's society ("Morals. Ethics. Nowadays they seem like elderly relatives that we trot out on Sunday for family reunions when we're feeling expansive." Marvelous), but it's tough to care about Dukakis' character when she comes across as so aggressively irritating and unpleasant.

The series' producers made a big mistake letting Claire Trevor disappear after her one-off appearance as Director of Nursing Veronica Johnson, in The Bed I've Made. In this very funny, sweet outing, scripted by Jean Holloway and directed by Don Taylor, Dr. Gillespie meets his match in Blair's new nursing head, falling quickly in love with her, although never saying as much, as well as arguing with her all the time, before he almost dies of pneumonia ("'Quarrels?' What a shabby little word for such splendid rows!" he crows, before he hilariously whines, "Don't argue with me! I've been sick!"). Trevor is perfect against Massey; what a pity nobody thought of keeping her on as a foil/romantic interest for Massey. A Time to Every Purpose continues a recurrent theme in this season of Dr. Kildare--self-delusion at all costs--as Betty Field (she knocks these kinds of characters out of the park) plays an overprotective mother who simply can not bear to tell her plain daughter she's lost an eye in a car accident. Judee Morton does well as the put-upon teen, and Murray Hamilton has a nice scene where his insensitive eye doctor character is coldly insulted by an angry Gillespie. If Love Is a Sad Song was the only Dr. Kildare episode you ever watched...I could see you shaking your head and blowing the show off as horribly dated. Dealing with the then-novel idea of women surgeons (someone states there are only 37 operating at that time in the U.S.), the episode proceeds to trot out every gender bias in the world as it examines Kildare's and potential surgical resident Diana Hyland's impossible love affair (you ain't kidding, Diana...). Whoppers include Kildare stating, "I don't know, something happens when women go into medicine...they lose something," to a fashion show in the hospital when they do a newspaper spread on Hyland, to a discussion about "wasting time" training a woman when she's just going to go off and get married and have kids. Oh well...at least you get Chamberlain singing, Hi-Lili, Hi-Lo. John Bloch delivers an engaging look at the ripple effect of malpractice suits in The Thing Speaks for Itself, when Kildare is sued for "killing" a patient during a risky procedure. Terrific cast in this one, including Fritz Weaver, George Macready (so slimy as a sharpie lawyer), John Williams as a cowardly physician who's been cowed by a previous lawsuit, and particularly Zohra Lampert as Williams' troublesome patient (the more I see her in these random roles she had in 60s and 70s television, the more impressed I am with her skills; she's more alive on screen than just about any big-time actress I can think of from that era). Massey has a nice bit at the end, pleading for the right to practice medicine--and fail--without the constant threat of lawsuits stymieing progress.

Whatever goodwill Jack Carter engendered from his first visit to Blair General this season, in Guest Appearance, is completely wiped out in the risible The Great Guy, where Carter plays a world-famous clown who loses his leg to cancer. Constance Ford, a class-act supporting player who could do a repressed, angry, bitter bitch better than anyone (A Summer Place is her best), gets good mileage out of her fated, faithful wife character; however, Carter is atrocious, grotesquely overacting (his repulsive bedside plea, "Love me! Love me! Why doesn't anybody love me?!" gets the only reaction it deserves: Massey watches impassively before kindly pulling his head back in sympathy for Carter the actor). Venerable Jane Dulo scores a nice little supporting turn here, though. The Mosaic, a snappy little medico-mystery outing from Jerry McNeely and director David Lowell Rich, plays like a backdoor pilot for Tom Tyron's Dr. William Ellis of the Health Department, as he tracks down a deadly hepatitis outbreak at Blair. Terminally one-note Tyron overplays the hail and hearty bit (watch him slap an unamused Chamberlain on the back), while future god James Caan slowly dies from "Papa Bug." Unknown Jena Engstrom pulls off the impossible in The Good Luck Charm: she almost out-acts legend Gloria Swanson, playing a dying young woman who needs to see Swanson's stage actress character just once before she kicks off (lovers of Swanson get all the histrionics associated with her image...as well as an absolutely superb bit of thesping at the girl's deathbed; Swanson's emoting is mesmerizing). Jail Ward, from scripter Jerome B. Thomas and director Jack Arnold, is an exciting entry with fascinating ethical overtones as Kildare keeps wounded cop killer Henry Silva in Blair's jail ward (who knew they had one?) for tests...while everyone else wants him carted off to real jail. Robert Strauss is good as the ward's top cop (this would have made a cool show), and James Franciscus (no doubt kicking himself for missing out on Kildare's success) is in fine form as a cop who just might kill Silva, vigilante-style. Interesting themes in this one, with the story having the guts to keep Silva an unrepentant killer. Gerald Sanford's A Trip to Niagara is a tense tearjerker when chemo Dr. John Larch (a fine utility actor you'll recognize from a hundred other roles) realizes he's inadvertently received a dose of radiation that will eventually blind him. A nervy brain operation offers a taut ending for this good offering.

That marvelous Zohra Lampert is back in Alvin Boretz' A Place Among the Monuments, an excellent outing where Kildare unfortunately learns the hard way that doctors simply cannot be placed on pedestals (those pedastals "crumble," Gillespie warns, and very few doctors "deserve it," he offers). Familiar face Harold J. Stone is good, as always, as Lampert's uncompromising--and terrified--father, while Lampert again scores with a low-key, believable turn (her death in the episode again underscores how Dr. Kildare strived to keep these stories realistic). Scripter Betty Andrews delivers another winner with Face of Fear, a solid, atmospheric outing for Robert Culp, who plays an intern who believes he has hereditary insanity (it's really epilepsy, with temporal lobe seizures). David Friedkin directs with an expressionistic eye (Culps seizure scenes are scarily blank-toned), while guest star Mary Astor, in just a few short scenes, scores big-time as a maiden aunt haunted by Culp's disease. John T. Dugan and John W. Bloch go the Tennessee Williams route in Sister Mike, a marvelously acted story about a poor Southern mother abusing her children out of ignorance...and love--a tough sell on their part to begin with, that then completely fails when we're shown the welts on the child's back (poetry is never going to sell child abuse). The performances, though, are stellar: effortless old pro Fay Bainter, the raw-nerved Collin Wilcox Paxton (in an impossible role), and little Mary Badham, who's remarkably precocious here. Robert and Wanda Duncan script a complex outing in A Very Infectious Disease, where visiting Australian intern Dan O'Herlihy (in a fierce, nuanced turn) must face the poisonous racism that infects him. Astoundingly, compared to what would be facile invective in a similarly plotted drama today, his racism isn't excused (Gillespie makes no bones about not tolerating it), but he isn't demonized, either--he's otherwise a kind, skilled doctor who's allowed to learn from his prejudice, and to be forgiven once he renounces it ("That's the trouble with us enlightened primitives: we always have to have something to blame on our own inadequacies,"). Criminally underrated Polly Bergen gets to show her considerable acting chops in The Dark Side of the Mirror, a highly entertaining entry from writer Dick Nelson and director Lamont Johnson, where Bergen plays twins, one dying from kidney failure, the other a good-time girl who doesn't want to be bothered with her sister's plight. I'm not sure I've ever seen sexy-as-hell Bergen look this good before (those insanely beautiful close-ups of her vie with those wowzer bikini shots), but more importantly, she kills here in not one but two emotionally complex performances that are as good as anything you're going to see from that era on television. One of the season's best outings.

Director Lamont Johnson (another unsung pro from the 60s and 70s who did fine work year in and year out) is back with the dreamy, strange The Sleeping Princess, scripted by Archie Tegland, where Kildare must pull hermit June Harding (very good here) out of her daydreaming limbo to face the real world. Lee Meriwether, looking D.D.G., has a funny bit as a nurse laughing at the curative powers of Dr. Kildare's inherent sex appeal. Ship's Doctor feels like another backdoor pilot, this time for suave, terse Patrick O'Neal, here playing cruise ship Dr. Robert Jones, with vacationing Dr. Gillespie along for the ride...and Kildare, barely seen in this one, stuck back at Blair (The Love Boat did it better...). A Tightrope Into Nowhere gets back to the show's formula when Kildare must make a difficult decision: should he take a dying father--a hopeless case--off life support right now, as cold, impersonal bastard Dr. Edward Asner advises (just the kind of doctor we need now with Obamacare), or keep him going so his troubled daughter Mary Murphy can have the time she obviously needs to accept his inevitable death. No easy answers in this one...but Gillespie does side with Kildare's ultimate decision (of course). Jerry McNeely writes a faith-based episode, The Balance and the Crucible, for guest star Peter Falk, who plays a doctor/minister who loses his faith when his missionary wife is killed by South American natives. Again, the series' overriding realism, married to an insistence on showing stories that highlight the elevation of the human condition (a disgusted Falk, feeling like a hypocrite, gives words of religious comfort to a dying woman, only to find his own faith again), is on display with this thoughtful entry. One of the season's best, The Gift of the Koodjanuk, finds Brian Keith (another woefully underrated performer) giving one of his career-best turns as a scamming Irishman who breezes into Blair as one of Kildare's "lost relatives," and proceeds to positively affect the lives of everyone he meets. It's a charming, heart-tugging performance from Keith, who was born to play this kind of blarney-spouting free spirit, aided by a fine, frequently quotable script from Walter Brough ("There's nothing more honest in the long run, than a good, straight lie,").

An Island Like a Peacock, from Gerald Sanford, feels a little too close to the similar A Tightrope Into Nowhere, with dying Forrest Tucker trying to come to some kind of truce with his blind daughter, played equally well by Kathryn Hays (look quick for Leonard Nimoy as her would-be boyfriend). Not much better is To Each His Own Prison (terrific title, though...), which finds Ross Martin hamming it up something terrible as a hopeless alcoholic who holds the key to an embezzlement case. The plotting is rather routine, with Martin (who always had a tendency to go over the top) not helping matters here. Look fast for George Kennedy paying his dues as an orderly. Much, much better is A Hand Held Out in Darkness, an intriguing outing that shifts from Kildare's baffling case of a catatonic Jane Doe (sweet, talented little Vicki Cos), to Gillespie's hilariously demanding efforts to have the hospital care for his sick grandchild (his daughter is nowhere to be seen this season). Despite what critics and Chamberlain himself asserted about his modest acting chops at this point in his career, I find him to be a natural, skilled performer at this stage of the game--watchful and listening--which particularly comes out when he's working with younger actors, like the adorable Cos. A winner. Finally, another season best comes in Adrian Spies' What's God to Julius?, a beautiful entry that finds Jewish baker Martin Balsalm (one of the best with this kind of role) dying of liver cancer, and wracked with worry not about himself...but with what is going to happen to his mentally challenged younger brother, Sorrell Booke. Notable, too, for not shying away from but highlighting the brothers' Jewish faith (we even get several scenes in Temple). An episode that will choke you up, sensitively directed by Robert Gist, What's God to Julius? is the kind of Dr. Kildare episode that best epitomizes the essentially positive, affirmative outlook of the series: Balsalm's death isn't the end of the story, but rather Booke's acceptance of his brother's death, and his own growing independence, are just the beginning.

The DVD:

The Video:

The fullscreen, 1.37:1 black and white transfers for Dr. Kildare: The Complete Second Season, Parts One and Two look remarkably sharp and clear (you can see the hairs sticking of Richard Davalos' ears in An Ancient Office), with correct contrast, a creamy gray scale, and some minor, occasional imperfections like dirt and scratches. Very nice.

The Audio:

The Dolby Digital English mono audio track has a moderate amount of hiss, but nothing too noticeable. No subtitles or closed-captions available.

The Extras:

No extras for Dr. Kildare: The Complete Second Season, Parts One and Two (too bad we couldn't have had just one short commentary track from Richard Chamberlain...).

Final Thoughts:

If this is just a "soap opera"...then we need more soap operas on TV today. Unfairly dismissed by snooty critics during its original run, and now just plain forgotten due to lack of visibility, Dr. Kildare, at least in this second season, delivers a wealth of intelligent, finely-wrought dramas, beautifully packaged and delivered, episode after episode after episode--can you imagine the sensitive, tortured geniuses of today's TV having to come up with 34 hour-long high-quality episodes like these in one short season? I'm highly, highly recommending Dr. Kildare: The Complete Second Season, Parts One and Two.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published movie and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||