| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

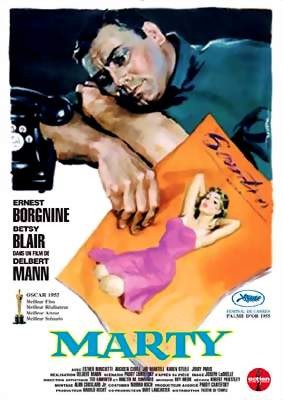

Marty

Paddy Chayefsky originally wrote Marty as a fifth season episode of the live television anthology drama The Philco Television Playhouse. That version starred Rod Steiger as unhappily single Marty and Nancy Marchand (later on Lou Grant and The Sopranos) as Clara, his prospective girlfriend. Steiger declined to do the film as the offer was contingent upon a multi-picture deal with producers Harold Hecht and Burt Lancaster, while Marchand's part was recast for complex reasons detailed below.

The movie of Marty is mostly excellent, but flawed. Ernest Borgnine, replacing Steiger, is very good if less the open wound that was Steiger's interpretation of the character. Betsy Blair, however, replacing Marchand, is miscast despite her best efforts to make the part her own. In expanding the material to feature length, the movie improves on the television version in terms of its location shooting in the Bronx, adding to the material a real authentic flavor, but Chayefsky's screenplay (he served as Associate Producer as well) also expands on the teleplay's weaknesses.

Kino Lorber's Blu-ray is part of a larger distribution deal with MGM, with the former apparently accepting whatever high-def masters the latter is willing to provide. (On the other hand, Kino Lorber did issue a statement on their Facebook page suggesting one of the problems with this release was entirely their doing.) In this case the transfer is rather disappointing. The black-and-white film lacks the crispness of other mid-1950s releases on Blu-ray (Criterion's Kiss Me Deadly for one, also United Artists, also from 1955). More urgently, Marty is presented full-frame, 1.33 (or 1.37):1, when in fact the movie was originally exhibited in cropped widescreen, apparently 1.85:1. Though less extreme than others, throughout the film are shots with way too much headroom and compositions are generally off.

As in the TV version, Marty Piletti (Borgnine) is an unmarried 34-year-old butcher in The Bronx. His customers and own mother (Esther Minciotti), with whom he still lives, are always on his case, forever asking him, "When are you gonna get married, Marty?" But Marty, stocky with a face like a Boston terrier, has all but given up on the idea. Instead, he aimlessly spends his Saturdays hanging out with other single men like Angie (Joe Mantell). "Whataya wanna to do tonight, Marty?" "I dunno, Angie. Whata you wanna do?"

One such Saturday his mother goads Marty into visiting the Stardust Ballroom, a dance hall. There, Marty meets Clara (Betsy Blair), a single, plain-looking schoolteacher callously dumped by her date that evening. The two lonely unmarrieds hit it off, talking excitedly about their lives until well past one o'clock in the morning, promising to meet again the next day following Sunday Mass.

Meanwhile, Angie is irritated that Marty had deserted him, urging him to give this "dog" he met "the brush," while Marty's mother has had a change of heart about Marty's future after her crotchety sister, Marty's Aunt Catherine (Augusta Ciolli), moves in complaining that her son (Jerry Paris) and daughter-in-law (Karen Steele) have all but abandoned her in her old age.

In the TV version, despite nearly identical dialogue Rod Steiger played Marty as a bitter middle-aged man who wore his emotions on his sleeve. A member of the Actors Studio, Steiger lost himself in the character, so much so that reportedly during Marty's dress rehearsal he experienced an emotional breakdown right in the middle of his performance. In the film version, Borgnine opts for a slightly different approach, burying his feelings, trying to be resigned to an imagined fate but constantly reminded of his loneliness by well-meaning family members and obnoxious neighbors alike. (I've always disliked Marty's last line of dialogue, in which Marty's says as much to Angie, in what comes off as petty sadism.) When I first saw the film version on commercial television 30-odd years ago, I much preferred Steiger's performance to Borgnine's. But, on a bigger screen and with the more intimate presentation that the Blu-ray format offers, I appreciate Borgnine's subtlety a lot more than once did. In particular an early scene of Marty nervously trying to ask a girl out on a date over the telephone is positively brutal and Borgnine nails all the racing emotions of such awkward situations expertly.

Much less successful is Betsy Blair as Marty's female counterpart. Most obviously, where Marchand was physically quite unattractive in the TV version, Blair is clearly nowhere near the "dog" everyone seems to think she is. She's not glamorous or particularly pretty, but by 1950s standards of physical beauty she's no worse than average. And where Marchand played Clara as an emotionally scalded woman even more fragile and pessimistic than Marty, Blair is never really convincing. In one scene inexplicably cut from some home video and television syndication versions of Marty, she rambles on excitedly about her date with her parents in their bedroom. In what should have been a funny, sweet vignette, with Clara expressing a broad range of excited emotions all at once, Blair instead comes off as mildly insane.

Apparently Marchand was considered, but Betsy Blair, then married to dancer-actor-director Gene Kelly, lobbied hard for the role. She had enjoyed a modest film career in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, but her outspoken Marxist politics led to her being blacklisted for several years. Surprisingly, her persona non grata had little to no impact on Kelly's career, which flourished unabated at MGM. Indeed, it was pressure from Kelly to cast her, with Kelly either refusing to report for work on It's Always Fair Weather at MGM or making threats against Hecht-Lancaster and/or United Artists (sources vary on the reason; neither makes much sense) that reportedly resulted in Blair's casting.

As Marty was originally written for live television, and thus necessitated the kind of scene transitions that would allow actors to change costumes, move from one set to another, etc., the TV version included arguably superfluous material, essentially to stall for time. Most of this material involved a subplot concerning the conflict between Aunt Catherine, her son and daughter-in-law, and later the aunt's destructive influence over Marty's mother. None of this material is anywhere near as compelling as all of the scenes with Marty, especially those with Clara. Yet, for some reason, Chayefsky chose to retain all of this material and even expand upon some of it. But where monologues of Marty talking about his loneliness remain absolutely riveting, this extraneous material seems triter than ever.

One example: Aunt Catherine warns Marty's mother to put the kibosh on this burgeoning romance, lest Marty suggest selling the family's old house and move into a nice little apartment. Literally seconds later Marty strolls into the kitchen, notices some cracked plaster and says, "You know, we ought to sell this old house and move into a nice little apartment." While Angie's selfishness toward Marty and Clara's romance is believable, throughout the film Marty's mother comes off as unbelievably wishy-washy, too easily swayed by everyone around her.

Conversely, the Bronx locations lend Marty enormous authentic atmosphere. Shooting extensively off the backlot and on locations beyond Southern California was still relatively rare in 1955, and rarer still to photograph such locations so unglamorously. Moreover, the use of real location and product names (the RKO-Chester theater, Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, etc.) further adds to the verisimilitude. (Most interiors were shot at the Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood.)

Whatever Hecht-Lancaster's original intentions with Marty, they sure knew how to market the Hell out of it once it was finished. Shrewdly, they opened it in the manner of an art house film, in art house-type movie theaters, patiently building an audience and glowing reviews before opening it wide. In proto-Miramax fashion they ended up spending more money promoting it than the film itself had cost, a strategy that paid off.

Video & Audio

For decades Marty has been a victim of that widely-held falsehood claiming post-1953 movies not shot in a special wide screen process (such as CinemaScope) were typically exhibited "full-frame," i.e., 1.37:1. But as historians like Bob Furmanek and others have taken great pains to unequivocally substantiate, the American film industry pretty much intended all open-matte productions for widescreen exhibition from 1953 onward, Marty included. Thus, despite Kino-Lorber's statement about wanting to ensure enough headroom in Marty's transfer, the full-frame presentation is simply wrong. It is not quite ruinous, just distracting at times when there's obviously too much empty space above the actors' heads. In a way, I found the bland, undetailed, and sometimes dirty picture quality more troubling. It's not clear if this is an old transfer or if only secondary film elements are available, but nothing about the image stands out at all. At least the film is complete, including as it does the scene with Clara's parents and the end titles-curtain call. The DTS-HD Master Audio (English mono only) fares somewhat better. No subtitle options.

Extra Features

The lone extra is a trailer.

Parting Thoughts

Not quite perfect, but for Chayefsky's and Borgnine's agonizingly painful portrait of rejection, low self-esteem, shyness and, ultimately, hope, Marty justifiably rates its classic status. Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian and publisher-editor of World Cinema Paradise. His credits include film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||