| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

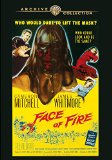

Face of Fire

The movie was directed, co-produced and co-written (with Louis Garfinkle) by Albert Band, who often with son Charles later became associated with the schlockiest of schlock movies: Dracula's Dog (1978), Ghoulies II (1988), Prehysteria! (1993), etc. But back in the 1950s the Paris-born Band was an extremely promising young talent. He adapted Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage for director John Huston in 1951, the movie notoriously compromised by executives at MGM, who hacked it to pieces and released it as a minor second feature.

From there Band directed Garfinkle's script of The Young Guns (1956), an offbeat Western starring Russ Tamblyn and Gloria Talbott then, also from a Garfinkle script, helmed I Bury the Living (1958) with Richard Boone, one of the eeriest, strangest horror films of the 1950s. Face of Fire was made in association with Svenk Filmindustri, apparently Sweden's leading production-distribution company.

Though dominated by American actors like Cameron Mitchell, James Whitmore, Royal Dano, and Richard Erdman, its startling credits include a musical score by Erik Nordgren (Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal), special makeup by Börje Lundh (The Magician, Through a Glass Darkly), and a few Swedish actors like Hjördis Petterson (The Pleasure Garden).

Warner Archive's manufactured-on-demand DVD offers an inconsistent but okay transfer that sometimes is crystal-sharp and at other times soft and mildly damaged. No extras.

In Crane's Whilomville, New York, in 1898, Monk (James Whitmore) works as a coachman for the family of Dr. Ned Trescott (Cameron Mitchell). Monk is especially beloved by Dr. Trescott's young son, Jimmie (Miko Oscard), whom Monk affectionately calls "Pollywog."

An early scene has Monk strolling through town in his best suit, demonstrating his popularity with the local ladies, though Monk's heart belongs to Bella Kovac (Jill Donohue), his fiancée.

A fire erupts at the Trescott home, and firefighters prevent the Trescotts from entering the conflagration to rescue a trapped Jimmie, but Monk bolts into the house, rescuing the boy. However, as he attempts to flee Monk is knocked cold in Dr. Trescott's laboratory, where acidic chemicals spill onto his face, horribly disfiguring him, leaving him virtually no face at all. (The makeup work is extremely good, with Monk's face authentically resembling a severe burn victim. Only his undamaged ears stop the work short of perfection.) Further, the burns are so severe as to cause physiological brain damage, or perhaps psychological trauma that affects his mind. Either way, after his injury Monk, wearing a thin black veil to hide his disfigurement, tends to wander about aimlessly and softly babble short, disconnected sentences.

The town at once hails Monk a hero for saving the boy's life while utterly terrified by his presence. While the Trescott home is being rebuilt, the guilt-stricken doctor makes arrangements for Monk to stay at the home of poor farmer Al Williams (Richard Erdman), who puts up with the arrangement solely for the money. Things come to a head when Monk, in his disoriented state, wanders off into town, retracing his steps from the night of the fire, frightening women and children. Soon, townsfolk are demanding Monk be institutionalized, or even hunted down like a wild animal.

It's unknown to this reviewer why Band and Garfinkle chose to cast James Whitmore instead of an African-American, as in Crane's novella. It may have been a box-office consideration, or perhaps they wanted to focus their attentions on Crane's criticisms of hypocritical prejudices toward the "monstrous" Monk without the additional complexities of its racial element. Regardless, what made it into the movie is extremely well done, as it tackles issues of fear, paranoia, and isolation; the paradoxical themes of monstrosity vs. deformity; how communities truly value acts of selflessness; how quickly they can as a group turn against popular (Monk) and respected (Dr. Trescott) members of the community, etc.

The performances are generally quite excellent. Mitchell is fine as the ethically tortured doctor, as are Bettye Ackerman as his wife, and Miko Oscard as their son. Whitmore is, expectedly, terrific as Monk before the fire; after that character's life-changing injury, Whitmore's faceless face is hidden behind a veil most of the time and mutters almost inaudibly, but his pantomiming is impressively expressive. Robert Simon, Richard Erdman, Lois Maxwell, and Royal Dano are all very good in supporting parts.

It appears older Swedish homes and other buildings were redecorated to resemble American structures, and this is quite successful. One doubts 1959 audiences had any idea they were looking at a movie set in America but shot entirely in Sweden. Band's direction is mostly straightforward but effective, with evocative little moments, such as the silent rush of the townsfolk to the fire, with only an alarm bell and the clanging of a fire truck piercing the nighttime air. Another fine scene has the doctor briefly think Monk might recover his mind, only to have his hopes dashed just as quickly. The movie doesn't aim for horror movie-type shocks, yet Monk's presence and movements after the accident are genuinely disturbing much of the time, even haunting.

Video & Audio

Warner Archive's 1.78:1 widescreen DVD of Face of Fire, like most other ‘50s Allied Artists titles, is sometimes on the soft side with slight damage (negative scratches, dirt), while at other times looks quite impressive. The Dolby Digital English mono is adequate, with no optional subtitles or languages offered, and no Extra Features.

Parting Thoughts

Unique and compelling, Face of Fire is Highly Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian and publisher-editor of World Cinema Paradise. His credits include film history books, DVD and Blu-ray audio commentaries and special features.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||