| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Mission: Impossible - The Original TV Series

The new DVD set has one major advantage in that it's considerably cheaper, currently marked down to $75.90, with an SRP of $129.99. It also has a major disadvantage, however: it's profoundly ugly and unwieldy, far less attractive and convenient than the individual season sets. The box, with abstract art including bullet holes and something like a shoot-out, doesn't really reflect the flavor of the original show. More alarmingly, the 46 DVDs inside are bizarrely organized, with two oversized cases containing seasons 1-3 and 4-6, while a much smaller, double-sized DVD case virtually orphans season 7 from the rest of the series and visually throws everything out of whack. Inside, the packaging subdivides shows by season, listing only episode titles and nothing else. If you're looking for a specific episode but don't know the title, good luck.

Still, the price is right, and it takes up a bit less room than the individual season sets did, all told.

The series' famous machine gun pace, epitomized by an iconic opening that in quick, very contemporary cuts preview the episode to follow, was way ahead of its time. When it was new, CBS was concerned that its complex, adult storylines and at times frantic narratives might be too much for Middle American viewers to follow. Looking at it now, four decades after it premiered, it almost plays like a brand-new series aiming for a '60s-retro look.

Mission: Impossible was born of the James Bond craze of 1965-66. It's essentially a spy show ingeniously structured within the context of caper/heist films of the sort popularized in movies like Jules Dassin's Rififi (1955) and Topkapi (1965) and the Italian-made Grand Slam (1967).

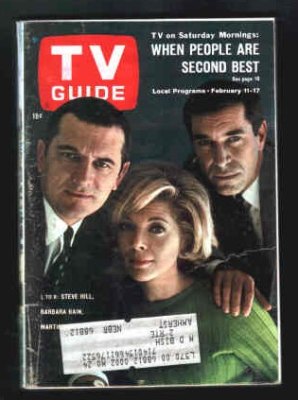

In the first season, Dan Briggs (Steven Hill) leads the Impossible Mission Force (IMF) on a seemingly, well, impossible mission. Shows open with Briggs working his way through a folder of glossy photos, theater programs, and the like, selecting the best talent to comprise each particular mission. In virtually every show, however, Briggs' team includes cool, curvy Cinnamon Carter (Barbara Bain), whose specialty is diversion; electronics expert Barney Collier (Greg Morris); strongman Willy Armitage (Peter Lupus), the muscle; and master of disguise Rollin Hand (Martin Landau who, apparently for contractual reasons, isn't billed among the regulars, but rather gets a "Special Appearance by..." credit).

The series was originally designed to include guest stars brought in playing other agents with various specialties. Wally Cox, for instance, appears in the pilot as an expert safecracker, while Star Trek's George Takei guests in another show as a biochemist. This facet was retained somewhat in later seasons but greatly deemphasized, especially after Landau and Bain became stars in their own right.

The program was the creation of writer-producer Bruce Geller, who had previously written and/or produced such above average TV Westerns as Have Gun Will Travel and The Rifleman. Mission: Impossible secured his reputation, though none of his later shows quite matched its success. (He did make one exceptional feature however, Harry in Your Pocket, a very good, offbeat film about pickpockets starring James Coburn and Walter Pidgeon.) Geller's scripts, along with other series writers like Jerome Ross, Ellis Marcus, and Alan Balter & William Read Woodfield, are consistently ingenious. In the pilot, for instance, the IMF has to steal two atomic bombs from an impregnable safe; rather than try to break in, their solution is ingeniously simple: smuggle the team's safecracker (Cox) into the vault and have him break out of it instead. In "The Carriers," the IMF infiltrate a meticulously recreated American town where foreign agents are being trained to act like ordinary Americans and carry a plague back with them to the real U.S.A. Briggs' strategy is brilliant: neutralize the plague but then allow the team to be captured, making it appear that their attempt to reach the toxic viruses has failed. In "Operation Rogosh," terrorist and mass murderer Imry Rogosh (Fritz Weaver) is kidnapped by the IMF, drugged into a state of unconsciousness, awakening in what appears to be a maximum-security prison in his Iron Curtain country - three years later! All of this is in fact an elaborate ruse to trick Rogosh into revealing his plans for an imminent bioterrorism plot in Los Angeles.

The strength of these clever scripts is backed up with outstanding production values for a '60s TV show. Production company Desilu (then concurrently shooting both Star Trek and The Lucy Show) spared no expense, hiring no less a talent than John Alton to shoot the pilot (it was, sadly, the great cinematographer's last credit), Lalo Schifrin to write the sensational score, and rising talent Bernard L. Kowalski to direct it. (Editors John M. Foley and Axel Hubert, Sr. cut it, setting the standard for all that followed.) The number of set-ups, the elaborate sets and location work, and number of extras confirm this was no cheap show. Subsequent episodes lean heavily on the Desilu/RKO/Paramount backlots, but still look expensive. (Later seasons favored the area around Yucca and Ivar, near the Capitol Records Building, and much of the last season was shot in San Francisco.)

Geller won two Emmys for the show's first season, as co-producer (with Joseph Gantman) of the year's "Outstanding Dramatic Series," and for his writing, while Barbara Bain won a Best Leading Actress in a Drama prize while her then real-life husband Martin Landau was nominated.

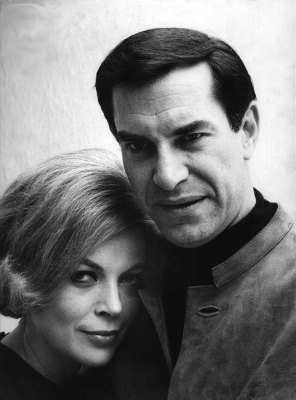

By spy show standards, the caliber of acting talent on Mission: Impossible is exceptional, with the ensemble giving extremely intelligent, low-key and subtle performances. Bain, who would be totally lifeless, like a department store mannequin, on her subsequent series with Landau, Space: 1999, is sexy and smart here; although she's an attractive woman, this sexiness comes from her performance as much as her outward beauty or her slinky wardrobe.

Lupus is an imposing presence and Morris gives exceptionally strong supporting performances, but the show really belongs to Landau and Steven Hill, the latter quitting after the first year when he couldn't come to terms with the program's grueling production schedule (rivaled only by another Desilu show, Star Trek), one that wouldn't accommodate his needs to observe the Jewish Sabbath. Hill, who later earned more acclaim as District Attorney Adam Schiff on ten seasons of Law & Order, was like Landau a product of The Actor's Studio, and his quiet amusement at capers pulled off was missed in subsequent seasons. Incidentally, the show's famous "this tape will self-destruct in five seconds" is only gradually introduced. The pilot has Briggs playing a self-destructing record album, while some of the audiotapes Briggs destroys himself.

With no explanation whatsoever, Peter Graves stepped into Hill's pole position for Season Two. Though Hill's marvelously low-key performance is missed, and while it's a shame the producers couldn't/wouldn't seize on the chance to explain his departure, the series maintained its high standards, skipping not a beat in the process.

Indeed, the show didn't become the big hit it eventually was until its second season. As former Desilu executive in charge of production Herb Solow and producer Bob Justman tell it in their fascinating book Inside Star Trek, both series were frequently over-budget and behind schedule, yet the executives at CBS were much more forgiving of perfectionistic creator Bruce Geller than perennial troublemaker Gene Roddenberry (Star Trek's creator) as by this time Mission: Impossible was critically lauded and a ratings smash.

Where Steven Hill frequently played a minor role in the actual missions, Graves's no-nonsense Jim Phelps is much more front-and-center, and a major part of the action.

Mission's third year (1968-69) would be the last for stars Martin Landau and Barbara Bain, then at the peak of their popular and critical acclaim. (Landau would enjoy a major comeback much later, however.) The exact reason the couple, married at the time, chose to leave the show is not known though it's generally assumed to have been over a salary dispute. It turned out to be a terrifically bad career move: they worked only sporadically for the next several years, possibly blackballed by Hollywood, before eventually moving to England to star in Space: 1999, a struggling series that didn't help their careers or offer them much in terms of their craft.

Mission: Impossible - The Fourth TV Season was suddenly minus all three of its original leads. Of course, Greg Morris and Peter Lupus were still on board and would be to the bitter end, but Lupus's function on the show was generally minor (for a time he was replaced by Sam Elliott as Dr. Doug Robert until the producers realized viewers loved and missed big ol' Willie) and Morris's character gradually became secondary to the Steven Hill-Landau-Bain and later Peter Graves-Landau-Bain combos.

In what must have seemed like an ingenious move at the time Leonard Nimoy, suddenly available when Star Trek was ignominiously cancelled, was cast as Landau's replacement, while various actresses were essentially tested over the course of the fourth season to replace Bain. Unfortunately, while Nimoy would seem like an ideal choice to fill Landau's shoes, his casting only amplifies the show's other growing problems, chiefly mechanical and repetitive scripts. Season Four episodes are watchable and entertaining enough, but the thrill is gone.

Nimoy, of course, had spent the previous three seasons playing the wildly popular Mr. Spock on Star Trek. Trek and Mission: Impossible, having started out as sister shows originally produced by Desilu in adjacent stages on the old RKO lot with some crossover of personnel, it made a lot of sense to cast Nimoy in what essentially was Landau's part in everything but name.

Watching these fourth season shows, the reasons for Nimoy's miscasting eventually become clear. Where Landau was a product of Lee Strasberg's Actors Studio and the Method, Nimoy seems to take a more intellectual, less emotional-instinctive approach. This served him well, famously so, on Star Trek where part of the fun was watching little flashes of humanity peek through the cracks of a basically emotionless character.

The problem on Mission: Impossible was two-fold. Master of disguise Rollin Hand (Landau) could play virtually any part in the IMF's elaborate cons. Nimoy, as The Great Paris, a magician, was more limited; he was fine playing emotionally distant intellectuals, but really wasn't up to the kind of sympathetic peasant/everyman parts Rollin Hand frequently played. Moreover, Mission: Impossible's format gave little time to show the characters, er, out of character. Ninety-five percent of the show was the Mission; there was never time to learn much about the series regulars' lives except for little flashes during the "apartment scenes," while they're being briefed about the upcoming mission. Somehow Landau always found little ways to express his character's humanity. He's not particularly demonstrative, but maybe he'd smile a little at mechanical genius Barney's (Morris) cleverness, or flirt a little with Cinnamon (Bain). In these scenes Nimoy tends to stand around looking very intense, an "I'm taking this mission very seriously" approach - and that's valid enough, but it doesn't invite the viewer to warm up to the character, either.

The other problem, somewhat related to the first, is that by the 1969-70 season the craze for spy movies and TV shows had pretty much petered out. Shows like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and I Spy were off the air, and the Harry Palmer, Derek Flint, and Matt Helm movies had ended. Mission: Impossible meanwhile was still basically the same show, albeit with wider ties, shaggier hair, and a lot more bright paisley suits. The show's rigidly structured format, initially appealing in its familiarity, had grown stale and the Big Cons that were surprising and unpredictable were becoming repetitive and easy to anticipate.

The producers seemed aware of this; they started testing the waters a bit during Season Four and by the following year decided they had pretty much exhausted the international espionage angle - considering that the IMF had visited about 150 fictional Iron Curtain regimes and South of the Border dictatorships, that's hardly surprising - moving the show toward more domestic storylines about the Underworld.

Thankfully, they left Barbara Bain's part open for the entire season, allowing for an interesting range of actresses to essentially screen test throughout the season. Lee Meriwether appears in the most episodes as Tracy (or Tracey). A few surprising faces turn up in this slot, such as Sally Ann Howes, fresh from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, but part of the surprise is watching who turns up where.

Lesley Ann Warren took over Bain's position as Dana Lambert in Season Five, also Nimoy's last. She's okay, but Lynda Day George as Lisa Casey, Warren's replacement for the last two seasons, is even better, the best of the various replacements after Graves.

By Mission: Impossible's seventh season, the Impossible Missions Force (IMF) consisted of leader Jim Phelps (Graves), Barney (Morris, this season sporting a mustache in some episodes), Willy (Lupus), and Lisa (George).

If that wasn't confusing enough, between the sixth and seventh season George announced she was pregnant, and is on maternity leave for a good chunk of Mission's final year. In some episodes her slot is taken over by yet another IMF recruit, Mimi Davis (Barbara Anderson, who had only recently departed Ironside, playing a similar part here, further confusing things), though like season four various women pinch-hit for the new mother. In other episodes Casey appears in a few scenes at the beginning and/or the end, her very-pregnant status discreetly hidden behind a lampshade, a puffy dress, or sofa pillows. Then for the rest of the show Casey works "undercover," hidden behind an elaborate mask or make-up - i.e., her part played by another actress.

This attempt to make Casey the center of episodes with actresses other than Lynda Day George stretches suspension of disbelief way, WAY past the breaking point. For instance, in the season-opener, "Speed" - filmed on location in San Francisco - Casey (played in most of this episode by Jenny Sullivan) masquerades as Margaret Hibbing (also Sullivan), the troubled, drug-addicted daughter of a mobster (Claude Akins). With little more than an elaborate Don Post-style rubber mask over her own features, and often only a few feet away from the gang leader-father, the bad guys never suspect Casey-as-Margaret. Even Margaret's drug-dealing boyfriend, who kisses and touches the fake rubber face doesn't catch on right away. To paraphrase writer pal Bill Warren, believability doesn't go out the window - it never enters the room.

Similarly outrageous is "Two Thousand," with the IMF tasked with getting rogue nuclear physicist Joseph Collins (Vic Morrow) into revealing the whereabouts of 50 kilograms of stolen plutonium. Phelps and his team come up with a wild scheme to make Collins believe he's suddenly recovered from a 27-year-long state of shock after the onset of World War III, that the year is 2000, and that he's now a 65-year-old man scheduled to be put to death in this dystopian future.

To achieve this the IMF, masquerading as police detectives, arrest Collins and sedate him when the "nuclear missiles" strike (a rear-screen special effect projected just outside a false window). They then apply old man makeup that, we're told, will melt after 12 hours. It's a big stretch assuming Collins would buy the E-ticket wizardry faking the nuclear holocaust and elaborate post-apocalyptic future and reveal the plutonium's location exactly as planned, but that he wouldn't realize that he's wearing rubbery old man makeup is absurd.

The "been there-done that" feeling permeating "Two Thousand" and several other episodes is not unwarranted. One's a remake of a first season show called "Operation: Rogosh" (discussed above) with Fritz Weaver in Morrow's part. In that more acceptable show only three years have supposedly passed, and there's no nuclear holocaust, but other particulars are almost identical, such as Barney masquerading as a prison inmate with a Caribbean accent. For its last season Mission: Impossible essentially remade several episodes from the Steven Hill first year, probably because those shows were out of circulation and not widely seen in the early '70s. Additionally, writer Stephen Kandel was hired to fix a backlog of heretofore-unusable scripts, unproduced stories with budgetary, structure or characterization problems. By this time it was simply less expensive to find a way to make those shows work than commission new ones. (This was apparently quite common in long-running series. The Twilight Zone also did this in its last year.)

Despite all the recycling and lack of believability, shows like "Two Thousand" are enormously fun anyway, and the outrageousness is actually part of the fun. The plot to make Collins reveal the location of the nuclear material is on the scale of an epic, multi-million dollar motion picture, involving not just the tight-knit IMF regulars, but also dozens of other players in on the gag, from speaking supporting parts to extras playing post-apocalyptic world soldiers, and what must have been massive cooperation from local government authorities. This episode is rife with high-tech gadgetry and elaborate sets; someone ingeniously thought to use the half-destroyed remains of a large hospital felled in the 1971 Sylmar Earthquake north of Los Angeles.

(The many co-conspirators are a significant change from earlier seasons, where taped messages made clear the IMF was on their own, and that the government would disavow their existence. Also breaking away from earlier seasons, seventh season shows dispense with the "dossier scene" entirely, replacing it with openers showing the villains and their operations prior to Phelps learning about them in the "tape scene." Many seventh season shows also toss in a wild card element, generally unrelated outside forces that threaten to expose the IMF team.)

At its best, even these last gasp episodes approach the greatest of the series when everything was fresh and frequently startling. "Kidnap," a welcome atypical episode directed by Peter Graves, has Phelps kidnapped in the opening reel by disgraced Syndicate chief Andrew Metzger (John Ireland, reprising a character he played in "Casino," from season six), who in turn blackmails the IMF to break into a bank deposit box. There's no tape scene, just Barney, Casey, and Willie under the gun to free their pal. The episode is a good showcase for doll-faced George, guest star Geoffrey Lewis has fun as Metzger's sadistic gunsel, Graves's direction is surprisingly good and, best of all, the show is complex yet also believable, a rarity by this point.

Video & Audio

CBS-Paramount went the extra mile remastering the entire run of Mission: Impossible. To begin with, the show looks great from beginning to end. The video transfers are far superior to all previous home video and syndication versions. The sharpness and color of these shows is extremely impressive. Episodes are in their original full frame format and are not cut or time-compressed. Typically there are four episodes per disc. The shows are offered in their original mono, but the audio defaults to a superb Dolby Digital 5.1 mix, which adds enormously to the show's excitement, and Lalo Schifrin's theme really comes alive. Beginning with Season 2, episodes are also offered with mono Spanish audio and English, Spanish, and Portuguese subtitles. Alas, no Extra Features.

Parting Thoughts

Mission: Impossible: The Original Television Series offers something like six 24-hour days worth of entertainment for a very reasonable price. The packaging is ugly and unhelpful but where it counts - the superb video transfers, great audio, and extremely high quality of the show itself - make this a must-have for classic TV and espionage fans everywhere.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian and publisher-editor of World Cinema Paradise. His new documentary and latest audio commentary, for the British Film Institute's Blu-ray of Rashomon, is now available while his commentary track for Arrow Video's Battles without Honor and Humanity will be released in November.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||