| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

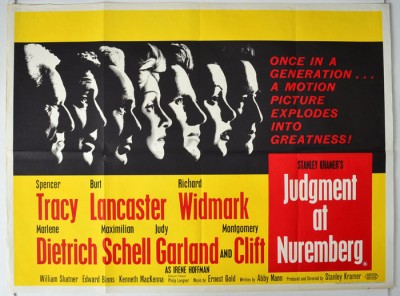

Judgment at Nuremberg

As I've noted in past reviews, Stanley Kramer remains singularly unfashionable among cineastes. His movies aren't given much serious consideration in scholarly film magazines, or shown by hip film societies. By their standards, he was Hollywood's homogenized liberal, who wore his heart on both sleeves in a series of well meaning but ponderous message films. This was perhaps best symbolized by Kramer's 1967 hit Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, a film about interracial marriage that was criticized by the left at least as much as it was by the right. How could liberal parents Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy possibly object, they said, to a prospective son-in-law as good and handsome and polite and educated and rich as Sidney Poitier? It's one of the mostly widely misunderstood pictures ever, a very fine film much better than many realize.

Kramer's last film was the dreary The Runner Stumbles (1979), and many would argue that Kramer himself had been stumbling professionally in the decades prior to his death in 2001. This reviewer remembers him in his last year at the Hollywood Collector's Show in North Hollywood, by then quite ill and in a wheelchair, selling signed copies of his autobiography and looking very much a forgotten man. His later film projects went nowhere, and quite unfairly he was ignored by the film industry at large. He never received an honorary Oscar, an AFI Lifetime Achievement Award, or similar recognition.

It's true his later films were often misguided or turgid, but they were nothing if not sincere - check out Bless the Beasts and Children (1972), a very weird but oddly compelling little film about saving buffalos. Conversely, he was one of the best and most socially progressive producers of the 1950s, and spearheaded a string of excellent films beginning in the late '40s. As a producer, he made cutting edge movies as diverse as Champion, Home of the Brave (both 1949), Death of a Salesman (1951), High Noon, and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T (1952). He began directing his own projects soon thereafter, hitting his stride with The Defiant Ones (1958), On the Beach (1959), and Inherit the Wind (1960).

The best of his films as a director though is certainly Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), the war crimes courtroom drama adapted from Abby Mann's famous television play, that had originally been produced as an April 1959 episode of Playhouse 90. The three-hour movie version is a bit overlong (Burt Lancaster's character takes forever to stand up and sit down again, which is about all he does for much of the film), but in its longer form it addresses such complex -- and for its time, quite controversial -- issues as global (including American) culpability for Hitler's rise to power, while drawing parallels to American judicial compromises during the early days of the Cold War in the name of political expediency.

The fictionalized account of one such Nuremberg Trial is set long after high profile Nazis such as Hermann Goring, Albert Speer, and Rudolf Hess have been sentenced or committed suicide. Instead, Republican Chief Judge Dan Heywood (Spencer Tracy) arrives at Nuremberg to sit in judgment of Nazi judges, including Ernst Janning (Burt Lancaster), a revered legal and constitutional scholar many Germans believe shouldn't be on trial at all.

As the Cold War emerges in the background, as the Soviet Union invades Czechoslovakia and tensions flair in Berlin, Heywood and prosecuting attorneys like Colonel Lawson (Richard Widmark) are pressured to go easy on a people whose proximity to the rising Iron Curtain becomes essential to the free world's defense strategy. In other words, they are asked to politicize their verdicts just as the German judges on trial had been pressured 15 years before.

The case has myriad ramifications, as demonstrated by brilliant defense attorney Hans Rolfe (Maximilian Schell, reprising his role from the TV version). Who is the braver man, he asks, one who flees Germany with the rise of the Third Reich, or the man who stays to try and serve his country's best interests? While judges like Janning admittedly ordered the sterilization of political undesirables, he is also shown to have personally saved the lives of others at his own peril.

And if Germany is guilty, what about the American industrialists who profited in rebuilding Germany's military might, or Winston Churchill, who praised Hitler's leadership as late as 1938?

It's questions like these that give Judgment at Nuremberg its teeth. There really was nothing like it until the superb television movie Nuremberg (2000), which also comes highly recommended. Nothing is cut-and-dried, and writer Mann gives even minor characters such as Haywood's aide (William Shatner, in one of his first film roles) and servants (Virginia Christine and Ben Wright) extraordinary depth. Ultimately, nationalism proves Germany's undoing as a whole, and for these the judges who knew better and who were in a position to challenge Hitler, it is their willingness to deny justice in the name of expediency and their "country's best interests." Of course, nothing like this could happen today, right?

The film is a real powerhouse of talent, with no less than four Oscar-nominated performances. Tracy is said to have been Kramer's alter ego in the four films they made together, the commonsense Everyman of which Tracy specialized and had no peer. He's superb here -- that great, deeply etched face so expressive. Montgomery Clift, in one of his last roles, appears in just one long scene, but it's quite extraordinary. As Rudolph Petersen, a victim of sterilization, Clift is unnervingly, clinically authentic. If not for his fame in Hollywood, one might assume he had been picked off the streets. Judy Garland is also quite good as Irene Hoffman, a German woman falsely convicted of illegal sexual relations with an old man, a Jew, who had been a friend of the family for years.

All three were rightly nominated for Oscars, but the only actor to win the award for Judgment at Nuremberg was Maximilian Schell, who is never less than riveting as the mercurial, yet somehow humanist defense attorney.

Some have accused Richard Widmark of being one-note as prosecuting attorney Lawson, but his single-minded swaggering, as it turns out, is dramatically justified. Of the leading cast, only Burt Lancaster, in inadequate makeup, is a disappointment. He's good but miscast, in a role that would better served by an actor less familiar to audiences, and probably one authentically German. (Curd Jürgens would have been ideal, for one. Supposedly Lancaster got the part after Laurence Olivier dropped out.) Marlene Dietrich is also excellent in an uncomfortable role she knew all too well: the German trying to come to terms with a simultaneous love and shame for her country.

Kramer's direction gives his top-drawer cast plenty of room, occasionally punching their scenes with interesting camera work (by Ernest Laszlo) that frequently circles actors during long stretches of dialogue with 360-degree tracking shots. These are generally done to good effect, with Kramer using the background to emphasize particular lines of dialogue, or to link characters to one another. He also seems to be one of the first to use the zoom as an aesthetic device, for punctuation. Though the effect would become a cliché within just a few years, Kramer uses the zoom judiciously; it's an effect that almost always enhances the moment.

The film uses a marvelous device to get around the language barrier. Early scenes have the Germans speaking German, the Americans English. Everyone listens to translations on headphones from simultaneous interpreters shown behind a glass wall. Kramer's camera slowly rises up above the level of the glass, and in a flash-zoom on Maximilian Schell, in mid-sentence his speech suddenly switches from German to English. In other words, German characters continue to speak in German, only we, the audience, hear all the dialogue in English. The effect is so seamless, one suspects many watching the film will not even notice what has happened.

Other technical credits are excellent. The film makes good use of real Nuremberg locations, impressively matching the location work with a couple of expertly executed matte paintings, studio interiors and, probably, Hollywood backlots. Ernest Gold's score, mostly adaptations of military marches and folk songs ("Lili Marlene" is shrewdly worked into one scene with Dietrich) is very effective. The film also has an excellent title design (by an uncredited Saul Bass?).

Video & Audio

Kino's Blu-ray of Judgment at Nuremberg seems to utilize the same high-def transfer as the earlier Twilight Time release. Reviews of many early Blu-ray titles noted how the enhanced resolution brought a new level of intimacy between the viewer and the actors onscreen. The added clarity made it easier to read the actors' subtle facial expressions, to almost be able to see into their souls through their eyes. That's an observation worth repeating here, for this excellent 1080p transfer only seems to improve the already great performances, a front-row seat versus high up in the third gallery. The added sharpness also brings to life the location work and cinematography generally; the polish of this production is even more obvious. Rather pointlessly, Kino's Blu-ray drops Twilight Time's decision to offer viewers the choice of viewing the roadshow or general release version, the former including an overture, intermission and entr'acte. Twilight Time's longer cut also offered a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1, which this Blu-ray lacks, though the 2.0 mix is still pretty robust.

Extra Features

Most of the supplements are repurposed from the 2004 DVD, and also present on the Twilight Time release. The best of the extras is a nearly 20-minute In Conversation with Abby Mann and Maximilian Schell (both now deceased). In what turned out to be an inspired idea, the writer and actor simply and casually chat face-to-face with one another about the project. After a few minutes of mutual admiration, they really warm to the subject, making pointed, spirited observations about the work and, among other things, discuss the TV version (both pay tribute to Claude Rains, who played Tracy's part on TV); Maximilian's status for years in Germany as "the little brother of Maria Schell"; their collaboration years later on a Broadway version, in which Schell played Lancaster's role.

The six-minute The Value of a Single Human Being focuses on Mann's script, and he reflects on its relevance then and now. A Tribute to Stanley Kramer, running 14 minutes, is only okay, consisting mainly of an interview with the actress Karen Sharpe (The Disorderly Orderly), Kramer's wife from 1965 until his death. All three featurettes are in 4:3 standard format.

Also included is a Trailer that, like many of Kramer's films from that time, hard sells its virtues, one of the reasons critics and audiences eventually stayed away.

Parting Thoughts

It may be unhip to admire a Stanley Kramer movie, but Judgment at Nuremberg really is a great film. The Blu-ray finally provides the superb presentation the picture deserves and, all told, this is unhesitatingly a DVD Talk Collector Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||