| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Mon Oncle Antoine - Criterion Collection

THE MOVIE:

Director Claude Jutra's 1971 period piece Mon Oncle Antoine is a cinematic pseudo-memoir that fits snuggly in the category with films like Fellini's Amarcord or Hallstrom's My Life As a Dog in that it's evocative of a certain time while also capturing the specificity of being a young man of that time. Jutra's tale is dreamy, awkward, nostalgic, and sexy, all words that could be applied to those other films, as well; yet, the setting of a mining town in 1940s Quebec means Mon Oncle Antoine is a story that is entirely unique to Jutra and co-writer Clémont Perron's experience even as they express the great commonalities of growing up.

The filmmakers' stand-in is Benoit (Jacques Gagnon), a quiet altar boy who works for his Uncle Antoine and his Aunt Cécile (Olivette Thibault) in their general store. Antoine is also the town mortician, which creates a dynamic of life and death in his store that is intriguing for his nephew but also a little scary. It's Christmas Eve, and the shop is newly decorated for the occasion, serving as a gathering place for the townspeople just as much as it is a venue for buying goods. Thus, everyone who has gathered to gossip and chew the fat can get an eyeful when the town's wealthiest woman, Alexandrine (Monique Mercure), comes to pick up her new corset. Spying on her in the changing room inspires sexual feelings in Benoit, just as Antoine and Cécile's other charge, the girl Carmen (Lyne Champagne), inspires love.

Story-wise, Mon Oncle Antoine reminds me of the classic image of small-town America as seen in Frank Capra films, or even more odd big-fish-in-a-small-pond international pictures like Local Hero (though Antoine is far more reserved in tone). Beyond the constant good-natured humor and the breadth of individual characters, the movies share a sense of community, where the working-class huddles together in good times and in bad, persevering as one as the times demand. Thus, a certain level of scorn is reserved for Carmen's father, who has abandoned the girl to working in the general store, only visiting to collect her wages for himself. The store being a nexus of the community means Benoit is going to observe all aspects of life, from its minor joys to its minor cruelties. Carmen and Alexandrine aren't just love and sex, they are lower class and upper class, economic polar opposites. His attraction to them both also has the greater gravity of arising within a mortuary. In his playful dalliance with Carmen, they run around the empty coffins while the girl wears a wedding veil. In one stroke, Jutra expresses both the infinite and the finite. Love is forever, but the individual is mortal.

There is a grim determination to a working town such as this one, where the unfairness of the system is accepted because no alternative is within sight. The boss at the mine can refuse raises to his workers, choosing instead to toss store-bought Christmas stockings from a moving sleigh, and no one will say a word, no one will stop their children from grabbing the goodies. The kids need some joy, and so the parents just silently watch the hollow spectacle. It's a wonderful scene, where Jurta and director of photography Michel Brault's documentary style is put to good use capturing the expressions of the young and the old, many of them real people living in the shooting location, Black Lake. Joining another boy in pelting the old man's horses with snowballs gives Benoit his first taste of pride, as the silent disdain for the boss turns to silent affirmation for Benoit's rebellion. (There is an added political element that the boss is English, and the rest of the town is French Canadian, a point only made subtly and likely to be missed if you don't know the history.)

It's not all happiness this Christmas, however; Benoit has harsher lessons to learn. From the start of Mon Oncle Antoine, we have also been watching the Poulin family. The head of the household, Jos (Lionel Villeneuve), is a wandering spirit, regularly quitting his job at the asbestos mine to go into the woods and be a lumberjack, leaving his wife and six children to fend for themselves. In any other movie, Jos would be a kind of rugged hero, the one who is not afraid to lash out against a life of inequality, but in Mon Oncle Antoine, he is more of a pitiful figure, a guy who can't commit to any one thing and likely moves on out of cowardice rather than true strength. His grim-faced wife (Hélène Loiselle) is clearly more noble, as she sticks it out and stays behind to take care of the family. Likewise, Antoine and his wife are shown as charitable parental substitutes for the abandoned Benoit and Carmen.

Jos' current walkabout, which ends almost as soon as it begins, seems to bring about a kind of karmic reaction. His oldest son gets sick and dies unexpectedly almost immediately after the old man heads for the hills. When Benoit asks to go along with Antoine to retrieve the body, it completes the cycle of life that we have been witnessing in the movie. In another case of extremes, when we first are introduced to Benoit, Antoine, and the assistant Fernand, they are officiating a funeral for an older gentleman who has just passed. On the other end, we have the death of someone far too young. In this event, Benoit will get his biggest lessons, learning that the adult world is not perfect or free. Death is arbitrary, and the people we think we can believe in will let us down. There are several wonderful literary metaphors employed by Jutra here, most of which I don't want to discuss for fear I'll give away too much. In some ways, the act of Antoine and Benoit going to retrieve the Poulin boy on Christmas Eve reminded me of John Huston's The Dead (a movie in dire need of a DVD release). Huston, adapting James Joyce for his final film, is completely on the other side of life from Benoit, however, and in the death of this young man, our hero is going to discover that youth is not a promise, that it is actually the end of a particular idealism. Benoit recoils when he sees the face of the dead boy, not just because he is seeing a corpse, which we assume he has seen before, but because for a second, the two adolescents look the same. Benoit recognizes himself in those lifeless eyes.

There is a fitting poignancy in realizing that Claude Jurta has cast himself as the conniving, libidinous Fernand. While the humanization of Antoine is one thing, Fernand's betrayal drives everything home for Benoit. In a way, this man is the in-between step, the connection between the idealism of Benoit and the disappointment of Antoine, who reveals his many failings in one drunken rant. Fernand is the rejection of consequence. He is belief in action, trying to get away with immorality, trying to live while rejecting honor. It's how you get from innocent youth to disenchanted old man. It's the director standing in the center of his own picture and serving as an agent of change.

Though my reference to The Dead is largely one to Huston, there is actually a greater comparison to be drawn between Mon Oncle Antoine and the short stories of James Joyce. As I said, Jurta uses a variety of literary metaphors, the kinds of images that would result in some wonderful prose. Benoit on the frozen ground after picking up the Poulin boy, or in the final scenes peering through the Poulin window, or even the understated dream sequence that brings all of his conflicted feelings together in a way that soothes his bruised soul, these are the epitome of cinema: expressing the interior through image alone. While prose would open a window into what is happening inside the boy, a filmmaker like Jurta must find a way to hammer home the same emotional resonance without explaining himself. Mon Oncle Antoine is full of many such images, but the director and Perron also achieve the desired nostalgia through the overall tone of the movie. The quiet of the piece, the unspoken, is heartbreaking. At the same time, by not being overly cloying with the period details, Jurta actually creates a sense of timelessness. The movie could take place in the 1940s, or it could take place now. It's not important. Mon Oncle Antoine is both contemporary and yearning for a time long past, demanding a change in the economic system even while celebrating a noble history.

THE DVD

Video:

Mon Oncle Antoine is given a new 1.66:1 transfer preserving its original aspect ratio. The image quality reflects the style of the early 1970s, so to modern eyes the picture might look a little faded or even, at times, grainy and almost like it has been duped, but this is really how it was shot and is not a fault of the DVD authoring. Michel Brault's photography has both the grittiness of documentary as well as the improvisation of early indie. The image has been cleaned of stray dirt or scratches and overall looks quite good, its slightly dated style adding to the air of nostalgia in the story.

Sound:

The original French soundtrack is mixed in monaural for this DVD, preserving its original soundscape. The audio is clear, without distortion or odd tones. There is also an English language dub mixed in mono.

Subtitles are available in English and have been created especially for this release. They are very good, maintaining the colloquial flavor of the dialogue.

Extras:

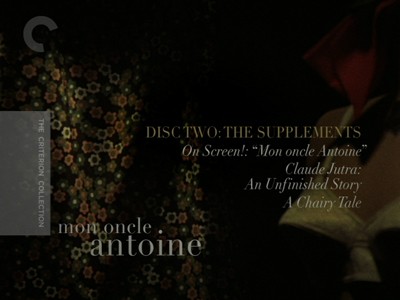

In addition to the movie, the first disc also has a theatrical trailer. The second disc is all supplements, and these three programs are as follows:

* "On Screen! Mon Oncle Antoine" (47 minutes): A Canadian TV production, tracing the history of Jutra from before and after Mon Oncle Antoine* Claude Jutra: An Unfinished Story (1 hour, 22 minutes): A 2002 documentary about the life of the director, looking at his creative spirit as well as the tragedy that dogged him and his films. Made by fellow filmmaker Paule Baillargeon and featuring testimonies from Bernardo Bertolucci, among others, it's an intimate portrait of an artistic mind. It's full of personal photographs, home movies, childhood experiments, and clips from his other films.

* A Chairy Tale (10 minutes): The 1957 short co-directed by Jutra and experimental filmmaker Norman McLaren. It's a humorous tale of a man who can't get along with his chair. Features music by Ravi Shankar.

The two-disc release comes in a standard-sized, clear-plastic case, with a cover printed on both sides so that chapter listings and artwork can be viewed when the DVD case is open. The interior tray has staggered spindles to hold both discs together. A 14-page booklet features a cast and crew listing, photos, and a new essay by Canadian film scholar André Loiselle.

FINAL THOUGHTS:

Highly Recommended. This French Canadian film is like a time capsule of small-town conditions in working-class Quebec of 1940, filtered through the wide-eyed curiosity of one boy. Helmed by pioneering Canadian director Claude Jutra, Mon Oncle Antoine - Criterion Collection is as universal as it is specific, a drama about life that is enlivened by genuine human comedy that anyone can relate to. Following the arc of events of one Christmas, we see the transition of time and the lessons learned. A two-disc release, the second disc features many informative extras to shed more light on how the film came about and who was behind it. Sure to be a special treat for those who have never experienced the film before, and one that will be just as satisfying over repeat viewings.

Jamie S. Rich is a novelist and comic book writer. He is best known for his collaborations with Joelle Jones, including the hardboiled crime comic book You Have Killed Me, the challenging romance 12 Reasons Why I Love Her, and the 2007 prose novel Have You Seen the Horizon Lately?, for which Jones did the cover. All three were published by Oni Press. His most recent projects include the futuristic romance A Boy and a Girl with Natalie Nourigat; Archer Coe and the Thousand Natural Shocks, a loopy crime tale drawn by Dan Christensen; and the horror miniseries Madame Frankenstein, a collaboration with Megan Levens. Follow Rich's blog at Confessions123.com.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||