| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Route 66: Season Three, Volume Two

Perhaps the best season of the series...even with the departure of co-star George Maharis. Roxbury Entertainment and Infinity have released Route 66: Season Three, Volume Two, a split-season offering (grumble) of the last 15 episodes from the CBS cult-classic's 1962-1963 go-around. George Maharis, the on-again, off-again co-pilot of Martin Milner's sweet, sweet 1963 Chevy Corvette, makes one final, inexplicable appearance here...and then disappears without the slightest explanation, only to be replaced, somewhat awkwardly, by Glenn Corbett's Army Ranger veteran, Lincoln Case (with Tod's now-forgotten one-shot co-pilot, Lee Winters, played by Robert Duvall, in-between Linc and Buz). As with the Season Three, Volume One episodes, the stories in this final wrap-up are as good as they get for the series (including what may be my all-time favorite Route 66 episode), and the ratings certainly were up from the previous season (less competition on its regular Friday night time slot, plus renewed interest in the series with Maharis' well-publicized exit). But you can't keep having one of the two lead characters inexplicably dropping out of the series without the format suffering - regardless of how good the writing is - and the audience's tolerance eventually fading away.

I written before about the first and second seasons of Route 66 (you can click here for the first volume of Season One, and here for my review of the complete Second Season), so I won't go into too much detail on the background and aesthetics of the series. The premise is simple, but the stories are quite layered. Straddling the time period (as well as the sociological and psychological road map) that lies between Neal Cassaday and Jack Kerouac's travels, chronicled in On the Road, and the coming counterculture hippies Wyatt and Billy of Easy Rider, who dropped out of society altogether, Route 66's existential wanderers, Tod Stiles (Martin Milner), Buz Murdock (George Maharis), and now Linc Case (Glenn Corbett), willingly flaunt the conventions of society (or at least "TV society") that expected young men like themselves to settle down and raise families, and to help maintain "the American Century" through their own industry and right living.

However, Lincoln and Tod were having none of that. Linc, a quiet yet potentially violent Special Forces Army Ranger, just back from a two-year tour in Vietnam, and Tod, a well-heeled prep school attendee whose comfortable world came crashing down when his beloved father died, leaving him penniless (except for that totally sick 1960 Chevy Corvette...which was updated, without explanation, with a new model each year the series was on, courtesy of the show's sponsor, Chevrolet), have no thoughts about marriage, no thoughts about putting down roots, and only go where the next bend in the road takes them. Occasionally, one of the boys will talk about putting down "roots" when they "find what they're looking for," but for the most part, the art of their lives lies in the traveling. They just have to move, to be free. It's important, too, that that rigid rudder of emotional stability (or instability, depending on the author) in most American fiction and storytelling - the father - is absent here. Even though Tod is stricken by the memory of the loss of his father, the gift of the Corvette has given him means to explore America his way, with no strings attached. As for Linc, his father is still alive, but their relationship is complicated by his father's expectations - expectations Linc doesn't want to meet. There's no one to go home to for Tod and Linc; that car is their home, endlessly prowling the great ribbons of highways and back roads that crisscross the country.

I grumbled in my review of Season Two that the originality and freshness of Route 66's concept looked somewhat stale by its sophomore session - what felt groundbreaking and quirky the first go-around seemed at times labored and too mannered in the second - an inevitability with the sausage-grinding aspects of network television production that by necessity stamps any artistic endeavor into a "product." Added discomfort came with the disappearance of George Maharis, who vanished during the last four episodes of that second season (and who splits for good after the first episode of this set). Reports vary as to what exactly happened (Maharis said a reoccurring bout of hepatitis; the producers said he was deliberately malingering to break his contract in search of movie roles), but I would imagine most loyal viewers of the series back in 1962 didn't have a clue as to why Maharis wasn't showing up on their sets (this was way, way before the omnipresent, voracious 24/7 entertainment news industry that now blights the airwaves). I supposed it didn't help, either, that the series just plain refused to explain his final exit. In his previous absences from the show, the writers would have Tod call Buzz at the hospital, where he was supposedly recovering from an illness. It was a gimmick that didn't work at all, but at least it gave the viewers something to hang onto while they wondered where Maharis really was.

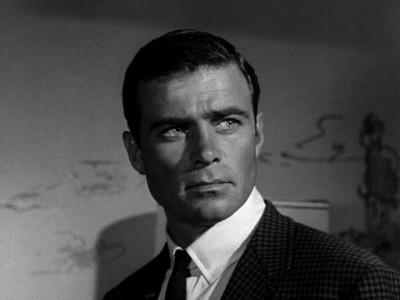

But after the first episode here, A Gift for a Warrior, Buz is gone and absolutely no explanation is attempted for his disappearance. Tod doesn't mention Buz to anyone; no phone calls to hospitals are made. Nothing. It's as if he didn't exist - a denial that probably didn't sit well with loyal viewers. Curiously, in the next episode, Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain?, Tod appears to have new traveling buddy: Lee Winters, played by none other than Robert Duvall. With zero explanation or background, Lee appears to have been traveling with Tod for some time; they're quite friendly with each other, and they banter like old pals. Shockingly, Lee even seems to have 'Vette privileges. Was this a try-out for Duvall as a potential co-star of the series? Or an experiment in possibly having Tod cruise around with different co-pilots during his journeys? It's hard to say. But Duvall is only around for that episode before he, too, disappears without any explanation. A few Tod only episodes follow, and then Linc is introduced. I suppose it's inevitable that comparisons will be made between the Linc and Buz characters, with many loyal Route 66 viewers siding with Maharis not only because he began the series with Milner (and that opening alchemy of original players in a series has a powerful hold that doesn't easily allow for substitutes in the minds of TV viewers), but because of Maharis' charismatic performance. Maharis did have that certain "something" that jumped off the small screen, giving Buz an edge, a danger, that contrasted nicely with Maharis' equally adept expressions of tenderness and existential angst. He played a jumped-up, hep cat out of Brooklyn who would not have been out of place in the various pieces written about the restless Beats who searched for meaning in a supposedly soulless America. And that nervy, jangly kind of energy balanced perfectly against the more wholesome, stolid questioning of Martin Milner's Tod.

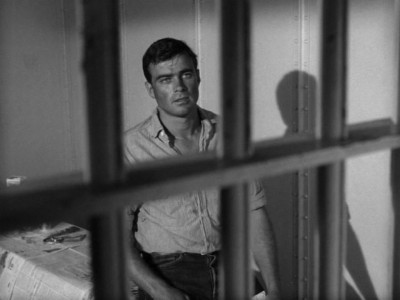

As for Corbett...that potentially explosive, nervous energy is missing within this calm, almost too-sedate performer. Corbett is quite good at playing strong and silent, but that only gets you so far with the thematically and motivationally complex writing of frequent scripter, Stirling Silliphant. Corbett's handsome but relatively inexpressive face just doesn't register the level of searching and pain and unease - as well as the hipster flights of poetic fancy and sheer joy of being alive - that Silliphant's writing routinely requires of his wandering heroes. Certainly series creator Silliphant gets kudos for introducing on television what has to be one of the earliest depictions of the coming emotional horrors that would plague tens of thousands of future Vietnam veterans, in the guise of Army Ranger Lincoln Case. In his introductory episode, Fifty Miles From Home, we learn that Lincoln not only served a tour in Vietnam, but that he was held prisoner there and had escaped after killing many of his captors (a traumatizing experience that leads to a pre-Rambo "Vietnam flashback" moment where Linc zaps a bunch of snot-nosed college kids for pushing him around). Later in the episode, he tells of a harrowing experience where he lost the women he loved to the Viet Cong. That not only Silliphant but the CBS network was willing to put this kind of character on television in 1963, indicting not only "war" in general but specifically, Kennedy's Vietnam, had to have been a quite daring political move for a weekly TV anthology to make at that time. And how the Linc character will resolve his identity with the military will have to be seen in the upcoming season (in these episodes, Linc is on extended leave, with his option to re-enlist a source of anxiety for him). But unfortunately, this potentially ripe character comes off as more wooden than mysteriously enigmatic under Corbett's listless thesping, undercutting much of the daring of Silliphant's conception.

That unfortunate factor, however, does not alter the fact that these remaining episodes of Season Three of Route 66 are just as fine as the first half of shows. In my previous review of that first half of Season Three, I wondered what effect losing Maharis might have on future episodes, and after watching these outings, the answer apparently must be, "None." Save for one or two acceptable but not exceptional episodes (The Cage Around Maria, Peace, Pity, Pardon), they are uniformly excellent, making the Third Season of Route 66 - at least from a writing standpoint - the best of the series. As usual with Silliphant's work on Route 66, one of his most prominent themes is the constant battle an individual wages over barriers (usually self-imposed) that thwart his or her efforts to achieve at their fullest emotional potential. Love, or more commonly, the lack thereof, is always the two ends of the same circle for Silliphant. Love and understanding are what we strive for, even when we harm ourselves deliberately to push it away, and yet, love is also a commitment to another person that requires some degree of sacrifice to our ultimate individual freedom. With love for another person (and acceptance of ourselves, faults and all), we can't win for losing, but we can come to some kind of understanding and peace with the unresolved nature of life.

And I can't think of a better example of this achingly bittersweet, temporary meeting of two lives destined to be parted, than Silliphant's The Cruelest Sea of All, which very well may be my favorite episode of the entire series. Tod and Linc find themselves working at Crystal River, Florida's world-famous attraction, Weeki Wachee, where spectators watch a spectacular underwater show where "mermaids" frolic in the crystal-clear springs. Tod works underwater, too, scrubbing clean the viewing windows, when he's not chasing after the various pretty divers who work as mermaids. Imagine his surprise, then, when gorgeous Elissa (Diane Baker) swims in from the springs and begins to poke around curiously at this "strange, new world." At first, Tod thinks Elissa is pulling some kind of gag to get a job, hinting at being "something" other than human to maybe enhance her chances, while pleasantly goofing on Tod and Linc. Later, he suspects she's another in a long line of damaged women he seems to encounter who hide in fantasy to avoid the complications and responsibilities of connecting with another human being. Linc, however, slowly begins to believe she may indeed be a mermaid, a notion confirmed by supervisor Donald McTaggart (Edward Binns), a wise soul who understands that we can hardly explain away a universe that is incomprehensible on every level. Unfortunately, Tod realizes too late that Elissa is truly "of the sea" before she disappears.

I realize that to some readers, that synopsis sounds faintly ridiculous, especially considering the poetic-but-all-too-real shattering of illusions that underpins many Route 66 stories. After all, Silliphant is saying...mermaids are real. Ridiculous, right? Well...not the way Silliphant approaches the question. To Silliphant, Elissa's reality is unquestioned - it's Tod's reaction to her that begs the viewer's increasingly incredulous response: "How can he be so uptight and logical and unbelieving in the face of a gift so lovely and ethereal and precious?" I don't think anyone on television wrote better about lost, beautiful, crazy women than Silliphant, but Elissa is never in doubt about her own self. And Silliphant's delicate-yet-direct scripting for her makes the character seem, without a doubt, real. This isn't something silly like Splash!; Elissa is what she is: a mermaid. And her indescribably sweet, naïve introduction to the human world plays beautifully against the increasingly stiff neck Tod offers in response to her awakening. What Silliphant is getting at here is what Silliphant is always getting at to some degree in many of his love stories: the inability for two individuals to get their perceptions of reality in synch with each other, regardless of how much they may love each other. Silliphant's embrace of an "altered" reality - a world where mermaids do exist - isn't used comically or from a fantasy/sci-fi perspective at all, but as a means for exploring most fully one of his central themes: love does not conquer all when we refuse to accept alternate views of reality - something we may be incapable of doing, anyway. An indescribably sweet, tender love story, simply and unobtrusively directed by James Sheldon, The Cruelest Sea of All also features what I think is the lovely Diane Baker's best performance. It's constructed with utter simplicity and without the faintest touch of parody or spoof or self-consciousness on her part (there's a beautiful scene where gorgeous Baker, swimming underwater, comes up to the glass and kisses it where Milner is, that shows an unrestrained delight on Baker's face - with Milner laughing delightedly, as well).

A more "straightforward" version of this classic Silliphant conundrum comes in Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain?, where Lois Nettleton gives a truly bravura performance as the quintessential Silliphant "ghost woman," an existential, cosmic misfit who floats in and out of peoples' lives, without a past or a future, operating outside the strict conventions of early 1960s America. Tod is brazenly approached one evening by glammed-up Nettleton, who sweeps Tod off his feet...and then promptly absconds with his credit card, running up a $9,000 bill. Sure that he's going to have to sell his beloved 'Vette just to begin paying off this debt, he suddenly comes upon Nettleton working at a Skid Row soup kitchen...only she claims to be someone else entirely. Tod falls in love with this aspect of her fractured identity, too, before she claims to be a third person, telling Tod on a stage at the UCLA Drama Department, that in her world, certainties like "love" and "home" and even one claimed identity, are luxuries she simply can't afford, and that she's destined to be utterly alone, no matter who loves her, nor how deeply she is loved. As I stated in my Season Three, Volume One review, Silliphant had an uncanny knack for framing beautifully poetic-sounding passages about life and love and truth and beauty within his quirky, restless narratives, a gift that gives many of Route 66' episodes an aural depth and complexity that was largely missing from most of the early 1960s' network television schedules. And Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain? is a perfect example of his facility to engage in flights of verbal fancy while espousing some truly troubling certainties about the desperate uncertainties of life for those who can't or won't toe society's conventional line.

Other standouts in these final 15 episodes of Route 66's Third Season include the tough, morally compromised actioner directed by Tom Gries, Shall Forfeit His Dog and 10 Schillings to the King, co-starring Steve Cochran, Barbara Shelly, John Anderson, and L.Q. Jones, which shows Tod (through Silliphant's fast-moving script) wondering aloud if he's witnessed murders or sacrifices to misplaced ideals during a posse hunt for a pair of thugs hiding out in the desert hills. In the Closing of a Trunk starts out with a shocking William Castle-like image of Tod being struck unconscious and stuffed into a trunk by a deranged Ruth Roman, but then backs up to be a typically Silliphantian exercise in past recriminations and newly-forged mistakes based on those former indiscretions. What a Shining Young Man Was Our Gallant Lieutenant is a terribly, terribly sad story from Howard Rodman, directed by James Goldstone, featuring Bewitched's Dick York in a moving performance as a former Army buddy of Linc's who, having suffered a catastrophic brain injury, has reverted back to the days when he was only eight years old. Corbett can't summon up the necessary pathos for this potentially devastating story, but York, along with veteran actors Jane Rose and John Litel as his elderly parents, are more than accomplished at getting across the heartbreaking tone of this truly memorable, moving episode. The always sexy, smart Janice Rule has a nice turn in But What Do You Do In March?, a not unfamiliar set-up for Route 66 - a rich woman preys on one of the boys for her own amusement - but which is double the fun here because there are two women looking to break the boys' heart (beautiful Susan Kohner appropriately fits the bill as "Heartbreaker #2" here). Who Will Cheer My Bonnie Bride? may not be a terribly original story - Linc is a reluctant accomplice to some robbers - but superlative performances by Rip Torn and Albert Salmi, and a short, funny spot by Gene Hackman, put this one over. Shadows of an Afternoon would have been a standout if Maharis had starred in it; as it is, we can concentrate on the always-underrated Ralph Meeker's superlative turn as a cynical lawyer, and icon Miriam Hopkins giving another startlingly good late-career turn as a delusional Southern matron.

Route 66 actually achieved its highest Nielsen rating this third season, jumping up to a modest 27th for the year, after languishing outside the coveted Top Thirty for its second season (it had reached 30th during its first season). Its lead-in, Rawhide, took a serious tumble this 1962-1963 season, but at 22nd for the year, still provided a decent opening pull for Route 66. Theoretically, Route 66 should have been pulverized by its new direct competition over on NBC: the previous year's sensation, Sing Along with Mitch, which had come in tied for 15th the previous year. But whatever appeal the show had in that particular line-up (Hazel helped a lot), dried up considerably this season, with the series dropping out of the Top Thirty altogether opposite Tod and Buz and Linc and that sweet Chevy 'Vette. The fourth and last season of Route 66 would see declining ratings again, as Glenn Corbett's Lincoln Case character failed to interest viewers in sufficient quantities.

Here are the 15 episodes included in the four-disc box set Route 66: Season Three, Volume Three. A small note: in the previous second season release, I complained about the episode descriptions on the disc holders' fold-outs being wildly inaccurate. This first volume of Season Three contains no episode descriptions, so...problem solved, I guess:

DISC ONE

A Gift For a Warrior

Tod and Buz befriend a shifty German illegal alien who's bent on revenging his wronged mother. James Whitmore, Lars Passgard and Carolyn Kearney guest.

Suppose I Said I Was the Queen of Spain?

Tod's credit card proves irresistible to a beautiful, strange woman who assumes identities at the drop of a hat. Lois Nettleton, Frederic Downs, Philip Abbott, Robert Duvall, and Harvey Korman guest.

Somehow It Gets to Be Tomorrow

A homeless kid steals Tod's wallet, and soon his heart, and he tries to spirit away his little sister from a loving foster home. Roger Mobley, Martin Balsam, and Leslye Hunter guest.

Shall Forfeit His Dog and 10 Shillings to the King

Tod takes part in a posse to round up some thieves holed up in the desert hills. Steve Cochran, Kathleen Crowley, L.Q. Jones, John Anderson, and Barbara Shelly guest.

DISC TWO

In the Closing of a Trunk

Tod works on a ferry, becoming involved with a murderess recently released from prison...who believes Tod is her son. Ruth Roman, Ed Begley, and Don Dubbins guest.

The Cage Around Maria

Tod, working at the Houston Zoo, rescues a young woman from the bear pit, only to discover greater dangers await her back home. Elizabeth Ashley and Beatrice Straight guest.

Fifty Miles From Home

Tod meets his new traveling partner: former Army Ranger Lincoln Case. Susan Oliver guests.

Narcissus on a Red Fire Engine

Tod's chance encounter with a captivating young girl in a bar leads to an emotionally volcanic situation. Anne Helm and Alan Hale, Jr. guest.

DISC THREE

The Cruelest Sea of All

Linc and Tod work at the Weeki Wachee attraction, but Tod gets a bonus in the bargain: he meets a real, live mermaid. Diane Baker and Edward Binns guest.

Peace, Pity, Pardon

Linc and Tod involve themselves with jai-alai players and Cuban rebels down in Florida. Alejandro Rey guests.

What a Shining Young Man Was Our Gallant Lieutenant

Linc discovers his old Army buddy has been horribly injured: he now thinks he's an eight-year-old boy. Dick York and Jane Rose guest.

But What Do You Do In March?

Tod and Linc get jobs as speed boat captains for rival rich girls. Janice Rule and Susan Kohner guest.

DISC FOUR

Who Will Clear My Bonnie Bride?

Linc is kidnapped by robbers and must decide whether or not to help them escape. Rip Torn, Albert Salmi, and Gene Hackman guest.

Shadows of an Afternoon

Linc makes the papers when he's falsely accused of cutting a little dog on purpose. Ralph Meeker and Miriam Hopkins guest.

Soda Pop and Paper Flags

A wandering bum is singled out as the carrier of a illness that strikes a small town...the town he grew up in. Chester Morris, Alan Alda, Joseph Campanella, and Tom Bosley guest.

The DVD:

The Video:

As with the previous half-season release, I was more than pleased with the full-screen, 1.33:1 transfers for Route 66: Season Three, Volume Two. The transfers, for the most part, look quite clean and bright, with a frequently smooth, creamy gray scale and minimal grain. Of course, anomalies do pop up, including scratches and dirt, with an episode here or there that look a little faded and blown-out (due to the original source material) but overall, not too bad at all.

The Audio:

And as with the first half season, I did have a problem with a number of audio tracks that sounded slightly squelchy or low to me. The English mono audio tracks, for the most part, are reasonably clean, with hiss apparent but not too distracting. But several episodes sounded subpar. Is this a matter of the transfer, or the original materials provided (I suspect the original materials, which no doubt are not the original master tracks)? Still, overall, they're acceptable. Annoyingly, close-captions are listed as available, but they didn't come up on any of my machines or monitors.

The Extras:

Some vintage commercials and bumpers for Route 66 are included as a bonus here. Commercials for Bayer Aspirin, Philip's Milk of Magnesia, Philip's Tablets, and a bumper for Chevrolet Presents Route 66 are included (I believe these are the same ones used in the first half season release).

Final Thoughts:

A superlative continuation of the best season of the series...even without George Maharis. The themes laid out in Route 66: Season Three, Volume Two just aren't explored in mainstream network TV offerings today, or if they are attempted, they're bowdlerized by either couching them in terms of sensationalism, or they're put forth with the intellectual and emotional facility and glibness of a People or US Magazine article. And unlike the whining and perpetually frazzled men/women-infants who populate our TV screens today, Tod and Linc, for all their existential doubts and questions, aren't overwhelmed with today's ubiquitous noxious cocktail of either anxious self-loathing or nerve-dead mockery of everything and everyone, masquerading as irony - a mixture of dread and defeatism that has seemingly infected almost all of our fictional American dramas on television today (as well as our politics, apparently). Tod and Linc are cocky about their wits, their hard labor, their efforts to win over girls, and they're open and understanding about their weaknesses. In other words: they're real men. I highly, highly recommend Route 66: Season Three, Volume Two.

Paul Mavis is an internationally published film and television historian, a member of the Online Film Critics Society, and the author of The Espionage Filmography.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||