| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Every Little Thing

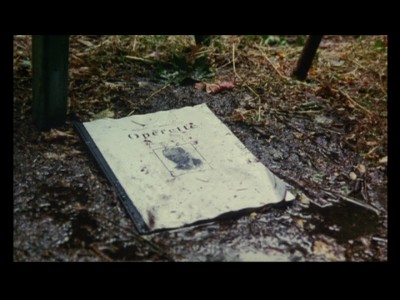

Both the loosely translated English title and the original French (La Moindre des choses, which would mean something more like "the least you can do" or "the least of these") of Nicolas Philibert's 1997 film relate intriguingly to its subject, the summer 1996 staging of Witold Gombrowicz's Operetta at La Borde, a renowned rural French asylum for the mentally handicapped that pioneered cooperative and creative methods of offering mentally ill patients a fulfilled and productive life. Does "every little thing"/"the least you can do"/"the least of these" refer, in Judeo-Christian biblical terms, to the patients themselves being the "least of these"--the most vulnerable, most dispossessed and downrodden of humanity--that Christ likened himself to? Is the title a challenge to the idea that the intellectual literary culture in which the patients are unexpectedly being invited to participate just extraneous, a "little thing"? Or is such a seemingly bold inclusiveness the the least we can do for them? Each of those meanings could apply at one time or another as Philibert's unobtrusive camera observes the patients and staff in their daily routines during the period leading up to the performance.

Those familiar with Philibert's relatively strict direct-cinema style (he also made To Be and To Have (Etre et avoir) and Nénette) will be prepared for the immediate, somewhat disorienting immersion into the world of La Borde, without introduction or thumbnail context. As we are not told directly what the situation is, we must watch and deduce for ourselves. Philibert's films are experiential and observational rather than informational or didactic, so there are no interviews, graphics, or intertitled explanations of what we are seeing; the patience of the camera as it allows moments to unfold asks us to set aside our impatience to "know" and develop our ability to just see. The languorous pacing seems especially fitting for this milieu, which, through Philibert's and Katell Djian's natural-lit outdoor cinematography, appears peaceful, idyllic, even utopian in its way.

We can, of course, see that the staff and directors of the play are "normal" people from the outside world, and the signs of the patients' developmental delays and/or mental illnesses are obvious; but no-one is defined through their role in any hierarchy, either in the creative endeavor or in the clinic itself. One of the La Borde's foundational purposes, despite the necessarily fixed roles of some staff, is not to run hierarchically, and Philibert is curious about, and wants us to see for ourselves, what that looks like and how it actually plays out. We are therefore not given any diagnoses or psychiatric explanations of the patients, whose visible symptoms range from practically undetectable to fairly severe communication and behavioral blocks. Instead, we get to know each individual, no matter their particular tics or challenges, through their self-expressions and interactions with others, sometimes in seemingly mundane situations. One long sequence records nothing but one patient sketching another, and it is only as we see the detailed, trying process of the sketch artist as she "directs" her model that it dawns on us that this exchange has a resonant analogue in the wearyingly repetitive, demanding work of the play's directors as they direct and re-direct their actors. The challenge of creation is universal, Philibert seems to be suggesting, however unusual or specific the attributes of those involved.

Although the film is constructed in a manner that eschews adherence to any latent plot or drama, the timeline from preparation and rehearsal to performance is inherent to the situation being documented, and so the film "leads up" to the patients' performance in front of an audience from the outside world, which also happens to include the late, highly regarded Witold Gombrowicz's widow, Rita. Perhaps the most salient proof of Philibert's quiet but persistent egalitarianism comes in his withholding of onscreen attention from this "celebrity"; we are shown the backstage excitement and nervousness of directors and performers, and the awed recounting of the experience of shaking Rita Gombrowicz's hand by one of the patient/actors, but the focus remains firmly on the event exclusively as experienced and measured by its participants.

Once the play is over, the audience has gone home, and the play's directors have left for a well-deserved vacation, the patients slip back into their peaceful routines. But there is a feeling of melancholy in the film's final shots, serving to remind us one last time of the innate human-ness of certain experiences. The strange mix of accomplishment and letdown felt at the end of a long and arduous communal endeavor, whether the shooting of a film or the mounting of a play, is not something that differentiates among us based on anything as ultimately superficial as illness or incapacity. As Every Little Thing demonstrates with such unassuming power, however easy it is to focus on what differentiates and divides one person from another, all it takes is a patient, respectful look to remind us of how much we all really do have in common.

THE DVD:

The transfer presented by Kino from a 35 mm print leaves something to be desired. The first, relatively minor problem is the apparent lack of any very meticulous print restoration in preparation for the transfer. This means less sharpness and clarity of the image and a blurrier, more grainy appearance, which is forgivable, particularly with the less-polished image quality that is endemic to Philibert's direct style of documentary filmmaking.

Less understandable is the non-anamorphic presentation of Every Little Thing. On a widescreen TV, the 1.78:1 image--whose aspect ratio, at least, is preserved--will appear as an annoyingly small rectangle within the rectangle of your screen, which is substandard at this point in the game.

Sound:The Dolby digital 2.0 soundtrack is faithful to the sound elements being used, but the sound shares the problem that somewhat mars the video: a less than pristine print, apparently neither new nor restored, has been used, and although the sound is adequate, there are occasional pops and some distortion on the rare occasion of louder dialogue.

Extras:None.

It is a shame that descriptors like "life-affirming" and "humanistic" have been rendered virtually impotent through overuse in reference to sentimental or simplistically feel-good movies, because they would be very apt for the cinema of Nicolas Philibert, which earns its humanism through the patient observation of its steady and attentive camera eye, avoiding condescending pity or soaring valorization. Every Little Thing documents a world that is outside of most of our experiences, yet Philibert approaches his subjects with a deep but unforced empathy that refuses to exoticize or sharply distinguish "them" from "us," taking the naturalness of their experience for granted. The transfer to DVD could have been done with a bit more care, but the film is Highly Recommended regardless.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||