| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Man Who Could Cheat Death / The Skull, The

Both films are interesting and The Skull is particularly good - it's an underrated and almost unique thriller. It's also the better looking of the two in high-def, though the upgrade of both titles, while noticeable, is rather slight. Filmed in 2.35:1 Techniscope, the high-def transfer of The Skull has good detail, eye-pleasing fine film grain, and good color, while the 1.66:1 The Man Who Could Cheat Death is a tad better than the SD DVD though inferior film elements were sourced. A trailer was included on the DVD of The Skull but this two-disc set offers no extra features at all.

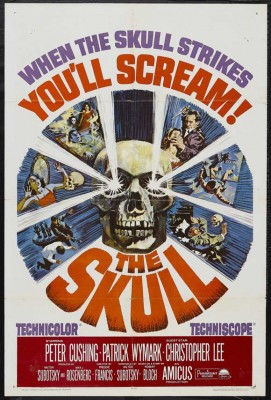

Flashy one-sheet poster aside (see above), The Skull is actually an impressively understated, psychological horror film. Star Peter Cushing is in typically fine form while Christopher Lee, in a "guest star" supporting part, delivers one of his most interesting and subtle performances. Each plays slightly against type, enough so one might have expected Lee in Cushing's part, and Cushing in Lee's.

The unusual film opens with a long, pre-credits prologue with almost no dialogue, while the last 20 minutes or so is likewise almost entirely visual. In the prologue, set in 19th century France, grave robbers unearth the corpse and decapitate the head of the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814). Later, a phrenologist (Maurice Good) dissolves the rotten flesh from the skull with acid, but there's a disturbance and his lover (April Olrich) discovers him inexplicably dead, the sight of him prompting a bloodcurdling scream.

After the titles, in present day London two obsessive collectors of rare occult items, Sir Matthew Phillips (Lee) and Christopher Maitland (Cushing), vie for a formidable set of figures at auction: statues of Lucifer, Beelzebub, Leviathan, and Balberith. A dazed Sir Matthew, bidding far more then the items are worth, emerges victorious.

Later, shady antiques dealer Anthony Marco (Patrick Wymark) invites himself into Maitland's study; his specialty is stolen merchandise. Marco first sells Maitland a biography of the Marquis de Sade bound with human skin, and the following night offers to sell him the skull of the Marquis himself. Maitland, skeptical about the skull's authenticity, is intrigued but noncommittal.

He meets with Sir Matthew who not only confirms the skull is genuine but adds that Marco stole it from his personal collection. Surprisingly, Sir Matthew is relieved the skull is no longer in his possession and urges Maitland not to buy it. He tells of its supernatural powers but Maitland dismisses this as wild superstition. Bad idea, Maitland.

The Skull frequently aired in television syndication throughout the 1970s and '80s. Back then I found it disappointing, though in retrospect part of the reason was that cinematographer-turned-occasional director Freddie Francis uses every inch of the Techniscope frame, and his compositions are greatly spoiled by television panning-and-scanning. For instance, there are a number of skull's-eye-view shots looking out through both sockets that on 4:3 televisions were effectively cut in half, to one socket and maybe a sliver of the second.

As a psychological horror film, The Skull is just terrific, with much more implied than explicitly shown. There are several interesting lighting effects, some similar to Francis's work as a cinematographer on The Innocents (1961), only this time in full color. The film has little in the way of special horror effects; one sequence of the skull floating around the room was accomplished with elaborate but visible wire rigging, but generally the photography is subtle and effective.

What really sells The Skull are Cushing's and Lee's performances and the long but chilling prologue and climax. Cushing has the juicier role in that his character gradually arcs from dismissive non-believer to panic-stricken victim. But for fans familiar with their work it's Lee's atypical role as a defeated, frightened man desperately trying to warn a rival/colleague that most impresses. Both play the kind of obsessive collector both classic horror film fans and DVD and Blu-ray collectors will surely recognize, and much of the drama hinges on their believable obsessiveness, which sometimes takes priority over their humanity (such as Maitland's interest in the flesh-bound book).

One associates roaming skulls with two-reel comedies - i.e., a parrot or some other animal gets stuck inside a skull, walks or flies about and scares the bejesus out of everybody - but Cushing and Lee also help ensure the roaming skull never seems ridiculous.

The film expands upon Robert Bloch's 1945 short story, "The Skull of the Marquis de Sade." Co-producer Milton Subotsky's script apparently included the dialogue-less prologue and climax and claimed that he saved the film in the editing room, though Freddie Francis later and more convincingly insisted those sequences were largely his doing. (He did make substantial changes to Subotsky's screenplay.) Either way both sequences work wonderfully well. Neither comes off forced yet their lack of dialogue subconsciously adds unease for the first-time viewer; these scenes aren't like other horror films of the period, and thus aren't as predictable while generating considerable suspense.

Subotsky and Max J. Rosenberg's Amicus Productions had a knack for hiring above-average talent to appear in their modestly-produced pictures, often because the parts were small and undemanding for the money. Besides Cushing and Lee, Wymark was fresh from Roman Polanski's Repulsion while Nigel Green (Zulu), Patrick Magee (A Clockwork Orange), and Michael Gough each have small but memorable roles.

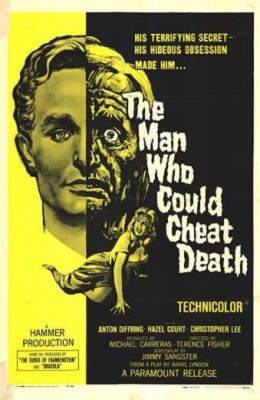

Of less interest is The Man Who Could Cheat Death, a talky Hammer film from their classical period, which though based on the Barré Lyndon play The Man in Half Moon Street more closely resembles a classed-up Monogram potboiler. Icy German-born actor Anton Diffring stars as Georges Bonnet, a late-19th century Parisian physician and artist actually 104 years old thanks to gland-transplant surgeries and glowing green youth serum that he keeps tucked away in a vault. There's a good shock scene near the beginning when his model-lover, Margo (Delphi Lawrence), refusing to leave, is witness to one of Georges's aging seizures. Like the serum, lighting and make-up effects turn his skin color a subtle green, while the pupils in his bulging eyes become larger and turn green also. In a very clever effect he puts his hand on Margo to prevent her from screaming, but his deadly touch only leaves a terrible hand-shaped burn scar over her mouth.

The increasingly mad Georges next becomes obsessed with former lover Janine Dubois (Hazel Court), whose nude figure he's sculpted - Court herself appears semi-nude, quite daring for 1959, and reportedly even appeared topless in an alternate, Continental version - even though she's since become involved with stuffy physician Dr. Pierre Gerard (Christopher Lee again). Georges is relived when his elderly but 15-years-younger partner-in-crime, Professor Ludwig Weiss (Arnold Marlé), arrives to perform another transplant operation, but Weiss has disappointing news: a recent stroke victim, he can no longer operate. Georges needs a new doctor - and quick!

The film was made at a time when Lee was still considered a supporting player rather than a leading man, and instead Hammer briefly regarded Anton Diffring as a kind of pinch-hitter for Peter Cushing when that actor wasn't available. He even played Cushing's role of Dr. Frankenstein in an unsold pilot made by Hammer, Tales of Frankenstein (also 1959). With his gray-green eyes, and sculpted facial features he vaguely resembles Cushing, but Diffring's ice water screen presence utterly lacked Cushing humanity - a humanity that made even Cushing's most sadistic villains interesting and even sympathetic.

On the other hand, Diffring was ideally suited to playing Nazi officers and the like - which he did well in films like Where Eagles Dare - even though Diffring's family had actually fled Nazi Germany before the war. However, he is quite good playing another obsessive doctor in the wonderfully lurid and sadistic Circus of Horrors (1960), so maybe Hammer wasn't too far off the mark after all.

Conversely Hazel Court and Christopher Lee, both famous for their parts in horror films, are miscast. Court was better suited to sardonic and villainous parts and Lee didn't certainly become famous playing bland if dashing heroes.

The film bears little resemblance to either the 1945 film of The Man in Half Moon Street or the play, and instead is like the kind of no-budget mad scientist films of the '40s from Poverty Row that used to star Bela Lugosi, George Zucco, and/or John Carradine, only with a bit more intelligence, better-appointed sets, and color photography.

Video & Audio

The Skull, filmed in two-perf Techniscope, is sourced from somewhat dirty and unsteady film elements, but looks comparable to other HD Techniscope transfers of similar vintage. Though there's room for improvement, visually the image is sharp with good color. The Man Who Could Cheat Death, in its correct 1.66:1 format, is more problematic because the film elements seem a step or two removed from the camera negative, and thus not as sharp but just as dirty as The Skull. However, it looks halfway decent and certainly better than all previous home video versions. The Dolby 2.0 mono audio of both films is adequate. There are no Extra Features, nor alternate audio or subtitle options.

Parting Thoughts

For fans of classic British horror, this double-bill is heartily recommended - even if, understandably, the consumer is frustrated at having to double-dip. For the price and for the okay high-def transfers, it's worth it.

Stuart Galbraith IV's audio commentary for AnimEigo's Tora-san, a DVD boxed set, is on sale now.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||