| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Eclipse Series 30: Sabu!

The set has no extras save for very good liner notes, while the transfers are yet another matter. The Drum may be Criterion's worst-ever DVD, video-wise. The first half is seriously marred by extreme video noise, including ghostly red horizontal lines painfully apparent much of the time. Rights holders ITV Studios may have supplied Criterion with the extremely inferior PAL-to-NTSC conversion, judging by the awkward motion further damaging the viewing experience. Fortunately, the other two titles are significantly better though far from perfect.

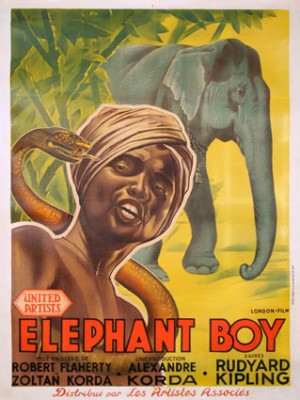

In Elephant Boy, 12-year-old Sabu plays Toomai, an aspiring mahout (elephant driver) who along with his father cares for Kala Nag (Iravatha), an extraordinarily tall and impressive Indian elephant that has been in Toomai's family for generations. Petersen (Walter Hudd) hires them and other mahout for a massive expedition in search of wild elephants. As Toomai struggles to gain acceptance among his British superiors and his fellow mahout, who mock him, Toomai's father is killed during a tiger hunt and Toomai's future becomes uncertain.

Adapted from Kipling's Toomai of the Elephants, a story in his The Jungle Book, the movie version was co-directed with great verisimilitude by documentarian Robert Flaherty and writer-director Zoltán Korda, both of whom were subsequently honored for their efforts at the Venice Film Festival. Flaherty, of course, was famous as the director of the seminal ethnographic documentary Nanook of the North (1922). Both he and Korda, a former cavalry officer, strive and succeed quite well integrating footage shot on location in Mysore (in southwestern India) with inserts, mostly involving the British cast, taken at Denham Studios in Buckinghamshire. Flaherty, presumably the main director in India, reportedly shot more than 55 hours of raw footage, and what survived into the film is consistently remarkable, from exceptionally cute footage of baby elephants at play to Kala Nag gingerly stepping over a real toddler laying placidly in the middle of the road.

Adding to the verisimilitude is Sabu himself, who was the real-life son of an actual mahout. It's clear throughout that Sabu was not doubled but rather is doing all the remarkable interaction with the elephant. Clearly he's not an actor who's convincing on an elephant but instead a mahout who can act. And with charm to spare.

I'd known Sabu from The Thief of Bagdad forward, but watching him here, so young, was for me something of a revelation. That's because (and I've never heard anyone mention this before) it seems quite clear Sabu was cast because at that age, 12, he very much resembled an Indian male version of Shirley Temple. Temple had been the Number One box office star in Hollywood for three years running, so it's only natural the film's producers would be inclined to cast someone exuding similar charms.

And Sabu does just that. In Elephant Boy his eyes open wide with wonder just like Temple's, he's curious like Temple, with similar facial expressions, talks like Temple (if with a thick Urdu accent).

As with other films produced by Zoltán's brother, Alexander, Elephant Boy is a handsome production with several eye-popping special effects. When a great herd of elephants is found, they're seen in wide shots that must be some kind of combination of miniatures and mattes, but it's so flawlessly executed it's a little hard to tell for sure. (**** 1/2 out of *****)

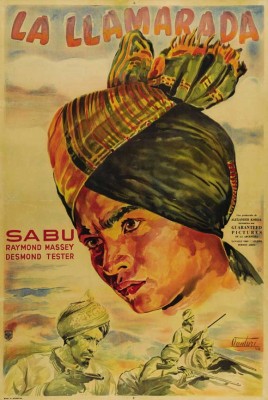

The Drum was the second part of the Kordas' unofficial "British Empire" trilogy that began with Sanders of the River (1936) and concluded with The Four Feathers (1939), a recent Criterion Blu-ray release. Though Sabu is top-billed as Prince Azim, his is really a supporting (and literally subservient) role to Roger Livesey's third-billed Capt. Carruthers in this very exciting and epic, if now politically incorrect, historical adventure, with Sabu firmly ensconced as a symbol of the contently colonized.

In the explicitly Muslim region of the Northwest Frontier (today the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region), the British governor (Francis L. Sullivan) negotiates a peace accord with wise King Tokot, but's he's assassinated by his evil brother, Prince Ghul (Raymond Massey), who usurps the throne. The king's son, Prince Azim (Sabu), is also targeted for assassination but manages to escape.

Fundamentalist Ghul plots to drive the British infidels from India, hoping to spark a nationwide rebellion by slaughtering Curruthers's regiment and diplomats on the last day of a religious festival (apparently Eid ul-Fitr, the last day of Ramadan). Azim's supporters see this as an opportunity to expose Ghul and expel the British at once, but Azim wants no such thing. He's become fast friends with his British conquerors.

In hindsight, The Drum's imperialist politics are fascinating and sometimes cringe-worthy. Here, the bad guys are the indigenous people while the heroes are the invaders imposing their Christian and British values. Imagine a Hollywood Western in which the son of a chief admires the uniforms (as Sabu does here) worn by the 7th Cavalry, and races to protect his white friends at Little Big Horn. Colonialist fantasy indeed.

Massey, however, is a marvelous, malevolent villain. He became famous for playing quintessentially American figures, particularly abolitionist John Brown and Abraham Lincoln (in several films and TV shows) but in fact Massey was Canadian and did some of his best work in Britain, including important productions like Things to Come (1936) and A Matter of Life and Death (1946), in which he again memorably sparred with Roger Livesey. In The Drum Massey is smooth, articulate and cunning. Watching him, it's hard to imagine that he wasn't a major influence on Conrad Veidt's very similar approach to playing Jaffar (opposite Sabu) in The Thief of Bagdad.*

Livesey was an underrated actor, his gentle screen persona also reflecting a naturalness that contrasted more famous Shakespearean headliners like Olivier. He is, of course, best remembered for his trifecta of classics for Powell-Pressburger: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), I Know Where I'm Going! (1945), and A Matter of Life and Death.

Sabu's scenes are less interesting, less important to the story, though his character does strike a warm friendship with young Gordon Highlander drummer Bill Holder (Desmond Tester), who treats the prince as an equal. It's a relationship not unlike those that turn up in almost every Shirley Temple movie, particularly the period ones.

The production values are very impressive, including a huge, Samuel Bronston-worthy set, possibly built in North Wales, though much of the picture was shot on location in Chitral, Jammu, and Kashmir, India. (****)

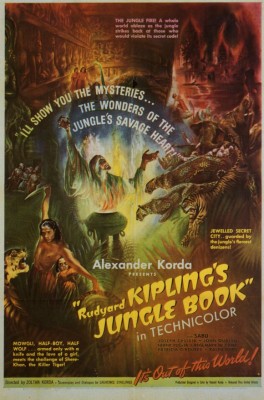

Jungle Book begins with elderly Buldeo (Touch of Evil's Joseph Calleia), entertaining a crowd and a British memsahib (Faith Brook) with fantastic tales of the jungle.

He tells the story of Mowgli, a toddler who wandered off into the thick jungle and, lost to his parents, is instead raised by a pack of wolves. Many years later, the teenaged Mowgli (Sabu) is discovered and captured. His birth mother, Messua (Rosemary DeCamp), agrees to care for him. (Mowgli's completely naked here, or supposed to be, though Sabu wears flesh-colored bikini-like shorts in this scene.)

There's a touching bit of characterization, the best in the entire film, when the guilt-ridden but kind Messua convinces herself that the feral jungle boy couldn't possibly be the same child she lost years before, yet there's no doubt that her heart is telling her otherwise.

Mowgli is alternately fascinated and repelled by civilized man, and bemused and saddened by his bloodlust. Imagine, killing for sport when you're not even hungry! He becomes friendly with Buldeo's daughter, Mahala (Patricia O'Rourke). One day he takes her into the jungle to show her a lost city where she finds its hidden treasure chamber, filled with riches. Greedy Buldeo learns of the treasure and becomes obsessed with finding it, while Mowgli is himself anxious to return to the jungle in order to confront the dreaded tiger Shere Khan.

Jungle Book is less notable for its ultimately unsatisfying screenplay than for its look, which is quite incredible. The picture was shot entirely in and around Hollywood, the Kordas having temporarily moved their unit there at the outbreak of World War II, during the production of Thief of Bagdad. Quite unlike nearly all Hollywood jungle movies, which are usually inexpensively faked on soundstages and/or filmed on nearby locations such as Griffith Park or the Los Angeles County Arboretum, Jungle Book is infinitely more elaborate and imaginative.

The picture uses every filmmaking tool available then, especially glass shots and optical matte paintings, large-scale miniatures, full-size jungle sets, with everything augmented with distinctly non-native greenery. The effect is splendid and unique. The jungle teems with pinks and blues and purples and yellows. It's far more realistic and yet highly stylized all at once. That it's also one of the most gorgeously photographed (by Lee Garmes and W. Howard Greene) three-strip Technicolor movies ever adds to its ultimate success. The DVD is okay, but only a film restoration and high-def release would do Jungle Book full justice, though given its public domain status, that seems unlikely. Miklós Rózsa's score is another major asset. (His score was the first commercially released soundtrack.) (****)

Video & Audio

Problematic. The Drum has serious problems. Video noise, taking the form of rising reddish, shadowy lines, is highly noticeable and distracting during the main titles and opening scenes. I was so surprised by how bad this looked, on a Criterion title no less, at first I thought something was wrong with my DVD player or TV monitor. Moreover, the transfer also appears converted from PAL. Panning shots and other movement is slightly off, with the kind of jerkiness one associates with PAL-to-NTSC conversation. Why Criterion accepted this transfer, presumably provided to them by ITV Global, is anyone's guess. The other two look somewhat better, though I did notice similar if less overt PAL-to-NTSC conversation issues with Jungle Book. Video-wise, I'd rate Elephant Boy and Jungle Book two-and-a-half stars while The Drum gets just one-and-a-half stars. The mono English-only audio, with optional SDH closed-captioning, is clean and clear. The discs are region 1 encoded. No Extra Features save for the useful liner notes.

Parting Thoughts

Three fine films, but one very substandard video transfer and two others no better than adequate. For now they'll do, I guess, but all three deserve high-quality Blu-ray releases one hopes will turn up in Britain (at least) in the coming years. Until then, Recommended.

* Sergei Hasenecz adds, "I would argue that Massey could readily have been influenced by C. Henry Gordon as Surat Khan in The Charge of the Light Brigade, which pre-dates The Drum by two years. Gordon also played the Russian bandit (Cossack?) Voronsky in Roar of the Dragon (1932). He was a marvelous actor of villains, especially exotic, foreign ones."

Stuart Galbraith IV's latest audio commentary is Godzilla vs. Megalon (with Steve Ryfle).

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||