| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Woman with the Five Elephants, The

Language and translation being among the main focuses of comparative literature, which was my own college major (and one that demands the acquisition of at least one additional language, readings in that language, and multiple exercises that might fall under the "translation" category), perhaps I'm more predisposed than most to find Vadim Jendreyko's The Woman with the Five Elephants a transfixing cinematic experience. Its subject is Svetlana Geier, a renowned German translator who has created, among many other works, the best-regarded German translations of Dostoyevsky from her native Russian, and it melds her life story with her philosophy and practice of translating texts, which is not just a mental process but an actually much livelier-than-expected act that we see played out before us in some detail, captured by Jendreyko's unusually perceptive camera. But that is where I think the interest of the film will extend far beyond those who already have an established interest in multilingualism and the very fraught process of transforming a text from the language in which it was written to another. In addition to being in part about a fascinating, complicated, and compelling life story that intersects with some of the most intense historical episodes of the last century, The Woman with the Five Elephants becomes a cinematic feat by virtue of its redefining an act that we may have thought of as purely cerebral and invisible into an action--and a rather intense one, at that--that we can see taking place, a way of thinking and approaching not just texts but the world that comes clear through the interaction of Jendreyko as interviewer/filmmaker and Geier as elucidator of her own captivating ultrasensitivity to whatever she's experiencing, whether it's a novel or a train ride or the preparation of a meal.

The film 's structure bookends its delve into Geier's dramatic, turbulent past with her present as a very aged, slow-to-speak woman whose very modest persona belies her mental razor-sharpness and position as an eminent figure in Germany's literary landscape. Jendreyko leisurely lets us spend time with her in her home, where she putters around and does the most mundane household activities before getting her tea and heading up to her office to work with a detailed, artisanal focus on matters of world-literary importance. We see her at work with her collaborators/sounding boards in always amazingly intent and sometimes even argumentative exchanges as they work out what the best German word or phrase is to convey the spirit and essence, as well as the accurate meaning, of Dostoyevsky's Russian. But what Geier does in that office is just one example of how "on" her perceptiveness always is; what this film shows us (astoundingly for something that would seem to be so unshowable) is someone reading in an expert and passionate way that permeates her every experience. Whether she is fingering the handmade linens that her mother left her as she irons them, peeling an onion, considering the ugliness of modern architecture, or observing the murals and friezes of a centuries-old church, she is always observing and processing, thoughtfully, beautifully, and effectively articulating that visual/aural/mental activity in language that could only come from somebody who's spent their life honing their vocabulary, sense of linguistic rhythm and poetry, and verbal precision.

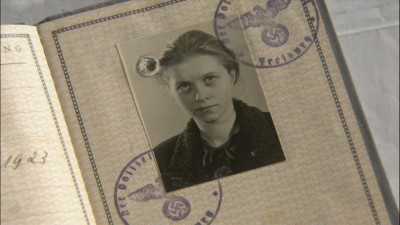

Where words threaten to fail Geier is in the film's exploration of the past and present familial tragedies that seem never to stop befalling her: In the present, her middle-aged son suffers an accident that devastates his life before finally taking it, and her past is a complex web of devastation at the hands of economic, social, and political circumstance; narrow escapes; and survivor guilt that impinges upon any peace she may have in her everyday life. As Geier, who has been invited to teach and lecture, takes the first journey back to her hometown of Kiev, Ukraine, since leaving it for Germany in the aftermath of World War II, Jendreyko takes the opportunity to complement her life story with archival footage and photos of her and her family back in the old country, with Geier dipping her toes into her own story with noticeably more tentativeness than she would enter into Dostoyevsky or Pushkin or a moving exegesis she can draw out of the fine threads of priceless inherited linen. As she did with the onion she made such an unexpectedly profound metaphor out of, Geier peels away the layers of her past, and we are made privy to her impoverished and oppressed life as the daughter of a political prisoner under Stalin; her early, self-instigated immersion in literature of all sorts that led to her life's overriding passion (even in the present, the highest compliment Geier can give to someone is that they are "well read"); and the dedication to learning German that saved her when Hitler's armies came to Kiev and, rather than being considered morally reprehensible, were greeted (at least by non-Jews) more or less warmly as liberators from Stalin despite the genocidal atrocities they committed there as elsewhere. The profound ambivalence Geier demonstrates as she tries to reconcile the way she was catapulted from increasingly desperate Stalinist oppression to a hopeful future of education and meaningful work with the fact that this salvation was provided by a no less monstrous regime whose destruction and evil somehow passed her over in a way Stalin's did not provides some of the most acute moments of the film, one of whose valuable points (among many) is its creation of a useful dissonance, a rift in our usual overgeneralization of historical events, figures, and "sides" that obliges us to consider the endlessly complex ripple effects of war and tyranny, and to hesitate before heedlessly indulging in any ill-advised oversimplification.

Jendreyko and videographers Niels Bolbrinker and Stéphane Kuthy (making good use of the clarity and vividness of high-def digital video) bring an aesthetically nuanced visual perceptiveness--a fine eye for composition, color, shadow, and light--to their documentation of Geier's work and journey(s), which, along with a supremely measured, intuitive, poetic rhythm of montage (courtesy editor Gisela Castronari), makes for a film that is both visually and temporally luminous. This is the first documentary I've seen since Chantal Akerman's superlative From the East (1993) (which it also resembles somewhat in its eastward-looking regard post-Iron Curtain from the vantage point of Western Europe) that just seems to nonchalantly, insouciantly subvert every single notion we have of what a documentary film is, can be, or should be (and makes even the best documentaries that follow more standard templates pale in comparison, at least when considered on cinematic terms). While it doesn't quite attain the absolutely unceasing, hard-won simplicity and visual perfection of Akerman's masterwork, it has some of that same mystery, that same irresoluble profundity that gets under the skin and haunts you in a way very few documentary works can manage, no matter how thought-provoking or consciousness-raising or well-made they may otherwise be. The stuff that The Woman with the Five Elephants is made of--the real-life stories and events that it documents--are certainly interesting enough, but this is a film that, in a way that has its analogue in Geier's expertise in getting to the very soul of the texts she translates, makes resourcefully artistic use of the tools of cinema to plumb every depth and patiently reveal what we thought was invisible and inexpressible, transfiguring its subject matter in such a way that it becomes something exponentially more than just the sum of its parts.

THE DVD:

The anamorphic-widescreen transfer (at an aspect ratio of 1.78:1, not, as the back cover incorrectly states, 1.85:1) is beautiful, conveying the crystal clarity and the luminosity of the film's beautiful DV videography in brilliant, near-perfect detail.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 soundtrack (in German and Russian, with optional English subtitles) is flawless; every nuance of the film's finely-recorded sound is here, with no audible traces of any distortions or imbalances.

Extras:--Portrait, a 28-minute documentary short from 2002 by Russian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa, who is documenting rural Russians and a forgotten, near-extinct agricultural way of life. Thematically, Portrait occupies similar territory to Bela Tarr's Sátántangó in its concern with people and places for whom the disappearance of communism and the onrush of capitalism is more a final blow than a liberation. Stylistically, Loznitsa has a Walker Evans-like sensitivity to human faces and bodies and the way they encapsulate experiences and conditions, as well as an eye for landscapes that evokes James Benning. The association with The Woman with the Five Elephants is quite loose (this, perhaps, could have been Svetlana Geier's fate had she remained in the USSR), but that hardly matters; the film is a bracing, gorgeous experience of its own, and its inclusion here is a not-untypical gift from Cinema Guild, which once again proves its dedication to giving us access to the best cinema has to offer--fine works that could easily have remained undeservedly obscure.

--The film's trailer, along with an assortment of trailers for equally must-see Cinema Guild titles (including their upcoming release of Béla Tarr's swansong, The Turin Horse).

Though quiet, frequently still, and reflective in its composed visual serenity, The Woman with the Five Elephants also bubbles with a degree of energy and life it can barely contain; by the time it's over, it has adroitly and profoundly covered a breadth and depth of thematic ground that would be too much for four or five lesser films. At the immediate level, it's a riveting exposure to the formidable intellect and philosophies housed in the deceptively frail, stooped, very elderly persona of translator Svetlana Geier. In its personal-historical dimension, it's one individual's journey into a troubled, contradictory past as well as a meditation on the displacements and reversals beyond any civilian's control that impose themselves on the lives of individuals as history takes its often violent and cruel course. Finally, on the grander historical plane, it's a convincing, disturbing reminder of how very different, how much less black-and-white, the movements of geopolitics and history look depending on whether you're looking at it from the inside or the outside, from the present or the past. It is also possessed of a visual sense that is at once sensuously beautiful and very carefully restrained/focused to match the moods and meanings of Geier's vocation and experiences as it records and conveys them for us. One gets the sense that its first-glance impressiveness of conception and execution is only the tip of an iceberg; as subtle and un-showy as it is, this film has a power that not only immerses you the first time around but suggests that multiple future viewings may be required to fully explore its astonishingly many enriching and edifying, consistently assured and finely-wrought layers. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||