| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Reel Injun

Reel Injun is a film with a knotty, fascinating, and important story to tell about the intersection of Native American history with the medium--the cinema--that was born just as that history seemed to be coming to a tragic, ignobly inflicted end. Director Neil Diamond (no, not that Neil Diamond) is himself a Native American of the Cree tribe (which inhabits a far northern region of Canada, near the Arctic Circle), and he attempts to give Reel Injun a framing device through his own personal, investigative road trip across North America to visit actual sites of significance to Native Americans while reflecting on the troubled, often treacherous relationship of Native culture to the way it has been depicted in the movies. Along the way, he enlists a wide array of commentators, interviewing contemporary Native American filmmakers, film critics, historians, and activists, all of whom contribute their perspectives to the film's accounting of the ins and outs of the movie industry's long-running (mis)representation of Indians on film, which are practically as old as the cinema itself.

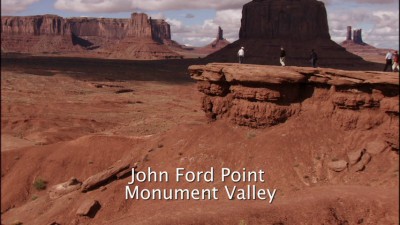

Diamond starts off by relating his own story/inspiration: He grew up on a reservation where movie nights were a big deal, the films' images of cowboys and Indians the vehicles through which Indian children themselves were exposed to the ideas of the culture at large about who and what they were. He then takes us along on his road trip, intercutting footage of himself, the places he visits, the interviews he conducts, and glimpses of real Native American life past and present, with many clips from films used as supporting examples of what's being discussed. From the beginnings of cinema, Indians seemed natural subjects; Thomas Edison himself made silents depicting the supposed customs and behaviors of Native tribes. But as the medium came into its own, films like Stagecoach and a great many other Westerns to follow were extremely problematic when it came to their frequently inaccurate, sometimes cruelly trumped-up and prejudiced depictions of American Indians. Diamond films himself visiting both John Ford Point at Monument Valley (the immortal location where Ford shot many a Western) and the Great Plains, contemplating how, for the purposes of Hollywood economy and narrative streamlining, Plains Indians somehow came to inhabit the Monument Valley desert. (That's only one misleading depiction of native peoples among many, of course; even ostensibly progressive representations like Dances with Wolves and Pocahontas come in for some well-deserved critical scrutiny here.). Furthering his investigation of this devil-may-care shifting around and blurring together of tribes that had their own geographical and cultural identities quite distinct from one another, Diamond speaks with Native American costume designer Richard Lamotte, who goes into some detail about the crude, ill-researched idea the movies usually have of the ways different Indian tribes dress.

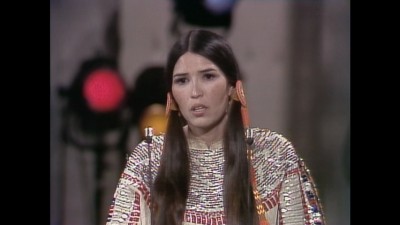

Diamond recruits Native American experts--historians Melinda Micco and André Dudemain; critic Jesse Wente; filmmakers Chris Eyres (Smoke Signals, whose writer, Sherman Alexie, himself a Native filmmaker, is conspicuously absent) and Zacharias Kunuk (The Fast Runner); activists like Sacheen Littlefeather (Marlon Brando's legendary stand-in at the 1973 Academy Awards) and John Trudell (the Lakota activist whose violent stand-off with federal authorities was the subject of Littlefeather's speech); and non-Native filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch (Dead Man) and Clint Eastwood (Flags of Our Fathers, whose Native American star, Adam Beach, also appears as an interviewee) who've dealt with the subject with some degree of insight or sensitivity--to comment on various aspects of the film's theme, for example the reductive melting-down of the hundreds of North American tribes spread out over the entire continent down into one familiar, warpainted, buffalo-slaying, arrow-shooting figure representing the "Indian," which is the source of one the film's most potent critiques. Of the types of movie Indian Diamond categorizes--the "noble injun," "the savage injun," and "the groovy injun,"--only the latter (e.g., Billy Jack) is generally a "cool" or positive stereotype to counteract all the condescending and/or negative imagery, and it came late in the game, brought on by general unrest and dissatisfaction with the American Way in the '60s and '70s.

To the film's credit, it offers varied and expansive points of view and is certainly no p.c. screed. Alongside its skeptical and enlightening dissections of the films themselves and their conveyance of dubious meanings about what and who Indians are, there is a simultaneous appreciation of the artistic merits of the pictures of John Ford, and of what Native actors like Chief Dan George (Little Big Man, The Outlaw Josey Wales) and Graham Greene (Dances with Wolves) were able to do with their prominent roles in movies where their characters played second fiddle to white men. (Diamond even visits some Navajo extras from '60s Westerns, now living in retirement on a reservation, who tell him that Indian actors would often slip subversive and profane elements into their dialogue, which they got away with because no-one else on set could understand a word.) One of the most captivating, erudite voices here is that of critic Jesse Wente, who offers a more cogent and articulate historical and aesthetic perspective than much of the rest of the film and also provides its most moving moment when, after Diamond has delved into the renaissance of Native American cinema over the last 15 years or so, he actually chokes up while discussing The Fast Runner and what it means as a Native viewer to see accomplished films made about aboriginal peoples made by aboriginal people.

All of this is both essential and interesting, but the journey Diamond brings us along for in Reel Injun takes many detours, and not all of them lead back to the main road. The film suffers from a surfeit of motion without having anywhere in particular to go; it sometimes feels like a compilation, not a structured, cohesive work with focused ideas or purposes. Stories that might make for a great in-depth doc of their own--that of Native American stunt coordinator Rod Rondeaux, whose emulation of exciting (if inaccurate) depictions of Indian horseback action he was transported by in the movies helped him into recovery from alcoholism; or faux "Indian" Iron-Eyes Cody, actually of Italian descent, who played Native in a hundred Westerns and was famously the head-dressed PSA Native whose single tear stopped a million litterbugs in their tracks--are truly interesting but overly truncated and not very well woven into the fabric of the whole, and the question of whether the film is a work of history, commentary, cultural criticism, or personal memoir is never satisfactorily answered. There is, of course, the possibility of it working in all these modes at once, but there is too often the frustrating sense that all these clips, all these voices, all this information have connections and overlaps at every juncture that the film just isn't bothering to make more explicit as a way of suturing it together a bit more tightly. It's like a tree with all the leaves and branches well-manicured for display, but no discernible trunk to trace them all back to. And Diamond's frequent sops to convention in the portions featuring himself don't help matters; scenes of him playing shoot-out with cowboys in a tourist ghost town, for example, feel self-indulgent and a bit silly, and some of the editing, narration, music, and mise-en-scène is just too corny, succumbing at times to mindlessly conventional documentary wisdom like gazing at a sunset=deep in thought and reflection.

Those drawbacks of disorganization and postcard banality draw off a significant portion of the film's energy and potential for incisiveness, but they can't negate the worthy, fascinating flashes of impassioned history and cultural commentary it also has to offer. Reel Injun is a lopsided effort, to be sure, but it has enough of a perspective, certainly a worthwhile enough mission, and it can fairly claim to reward an hour and a half of attention with at least a slightly broadened frame of reference and some substantial food for thought. One only wishes that a little more rigor had been brought to bear on the film's neglected and relevant topic so that it could have the resonating, galvanizing power it warrants--a power that Diamond only partially succeeds in giving it.

THE DVD:

The anamorphic, 1.78:1 aspect-ratio transfer is nicely done, capturing the varying celluloid textures of the film's multiple clips (some of which seem to be rough at the source due to age or print deterioration, not a problem attributable to the DVD authoring) and delivering Diamond's interview and on-the-road DV footage (which translates smoothly, as is usually the case, to digital media) with a minimum of noticeable aliasing, edge enhancement, or other compression artifacts.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo soundtrack is sharp, clear, and full, with all of the film's sonic layers--the music and Diamond's voice-overs, the interviewees' voices, and the at-one-remove sound of the various film clips--given ample space and power as they emerge from your speakers.

Extras:None.

Reel Injun does enough justice to the vitality of its subject--the (mis)representation of Native Americans over the course of cinema history, which has been part and parcel of the movies from the very beginning and has only recently begun to abate and head in a more positive direction--that it can't in any way be considered a failure. But it is something of a disappointment; its execution just doesn't quite live up to the vital potential of its concept. The surplus of clichés in director Neil Diamond's ongoing personal-diary interjections (which never quite convince us of their necessity in the first place), along with a lurching back and forth from one emphasis to another that too often loses the connecting threads that might have tied them together, make the film feel overstuffed, harried, and unfocused. Still, with a bit of mental rearranging and gap-filling effort on the part of the viewer and some help from the film's more articulate participants (I feel I could have watched critic Jesse Wente speak about cinema for the full running time and had a richer experience), there are glimpses of the more expansive and coherent film that could have been. And if one of the film's aims is to raise the viewer's awareness in and pique our interest about Native cinema, that mission actually is fairly well accomplished; Diamond may actually have done better to have gone less for breadth and focused more in-depth on the contemporary renaissance in cinema by Native peoples, which makes for one of Reel Injun's more successful segments (The Fast Runner, at least, is now on my must-see-soon list thanks to his work here). Hopefully, one day in the not-too-distant future, we will look back on Reel Injun as a nice, temporary placeholder between the time when virtually no filmmakers had the ambition to survey the troubled history of Native Americans and cinema, and the moment when Diamond continues his worthy project in a more systematic way or some other filmmaker takes the baton and runs a bit further with it. Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||