| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

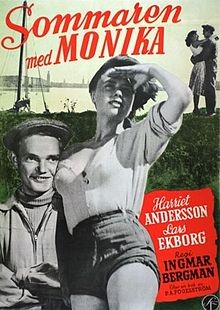

Summer with Monika

Please Note: The images used here are promotional and are not taken from the Blu-ray edition under review.

The inbuilt (and not really disprovable) suspicion on the part of young people in love that some latent tragedy always lurks within their overpowering emotions has long been a perpetually renewable resource for storytellers who can convincingly confirm it, with Romeo and Juliet and The Sorrows of Young Werther only the peak of a truly towering mountain of novels, plays, music, and films. In 1953, the great Ingmar Bergman, then still quite young himself, successfully tapped into that rich seam of potentially very affecting drama and emotion, adapting Pers Anders Fogelstrom's 1951 novel into a tender, intense film, Summer with Monika, whose forthright sensuality was daring for its time, though it now seems an early iteration of Bergman's own much more timeless cinematic sensuality (which extended, of course, far beyond just the erotic to encompass any physical entity, particularly the human face, that can be filmed). The film's tales of lovers on the lam, told in some indelible images and through unabashed but very skilled, fine-tuned performances, has all the pathos of a Bonnie and Clyde set in a more quotidian milieu, with the rousing defiance of young love meeting, by being worn away through the inescapable erosion of workaday worries and practicalities, a fate somehow worse than the violent, deadly, but glorious martyrdom of Monika and Harry's Depression-era counterparts.

Harriet Andersson began her long-running collaboration with Bergman spectacularly here as the young woman of the title; rarely has a young actor seemed to encapsulate the flippancy of youth with such spontaneous energy, so immediate and alive in all verbal and body language that it reverberates throughout any scene she's in. Faced with this much boundless, un-self-conscious beauty, it's inevitable that Harry (Lars Ekborg), the personable and nice-looking delivery boy that Monika meets in a bar while the two are on a coffee break (he from his duties and her from her drudge work at a downscale grocer's), will fall head over heels for her. The two go on dates to the movies and make out on park benches; Harry is driven by his newfound love to distracting daydreams that further compromise his already precarious position at the dinnerware firm he delivers for. The lusty, sassy Monika feels a deep connection to the heavy-handed but infectious romance depicted on the cinema screen, and she bemoans the stark contrast between her and Harry's lives and the much more glamorous joy and pain experienced by their amorous analogues in her favorite movies and magazine stories. Harry and Monika are working-class, living in noisy, crowded neighborhoods and, with Harry's ailing father and Monika's many hungry siblings to take care of, work and what little money there is to be made takes precedence over romantic flights, which the two hard-worked youngsters have to steal wherever and whenever they can. The couple introduced themselves to each other with a throwaway joke about taking one another away from their oppressive humdrum, but when the demeaning hassles of Harry's job and Monika's running away from home after a beating at the hands of her drunken, boorish father cut what's solidly tying them down and gives them the chance, they take it, stealing away from the city in Harry's father's boat and heading out into the wilderness just as summer is transforming it into a sun-drenched lover's paradise.

A gratifyingly disproportionate amount of screen time is spent on Monika and Harry as they truly come to an uninhibited, carefree, clothing-optional, alive state of existence during this sojourn, which both hope will never end but fear (with good reason) will have to. In this idyllic interval -- the film's creamy center -- a perfect balance is struck, the precise happy medium attained between a simpleminded Blue Lagoon vision of lovers in "natural" paradise and a Herzogian/Deliverance-style focus on Mother Nature's infanticidal side, which is to say that the summer skies and the sun's reflection in rippling waters are ravishingly gorgeous, as are the frolicking bodies of the now-unrestrained Harry and Monika, including Andersson's lovely derriere skipping scandalously unadorned down the shore, but at the same time, the business of what to eat, how to take shelter from summer rainstorms, and the lack of protection from marauders -- i.e. the necessity of surviving, even in a setting that allows for more freely expressed joy and lack of societal worries -- does not just go ignored. The moment that perhaps best exemplifies the film's youthfulness, in the form of its embrace of a Thoreau/Rousseau-indebted take on the nobility of surviving in nature, as opposed to merely surmounting the human-made obstacles of civilization, comes when a malicious camper sets fire to their boat while Monika and Harry are playing nearby and the two must vanquish this encroacher, thus proving their capability and strength (and, the film unavoidably succumbing to then-current gender code, Harry's "manhood") by relying on their own strength and wits, not civilizing laws, to protect their territory. But the film gradually withdraws its embrace of back-to-nature, with the seeds of their hopeful but naïve escape's temporariness having already been sown via struggles like the dearth of suitable nourishment to be found by humans in the wild, coming to full fruition with Monika's pregnancy, an utterly " natural" occurrence that paradoxically forces them away from nature and back to the city, where the hopes of a healthy baby and supporting a family seem more realistic than amid the now not-so-appealing freedom of exposure to the elements.

The tragedy of the film is that the compromises necessary to sustaining affection amid the regulatory impingements of society and routine are absolutely terminal for a love so insistently idealistic and self-consciously "pure" as that between Harry and Monika; the city, as depicted by Bergman upon their return, is a welcoming and reassuring beacon of civilized prosperity for those willing to accept its demands but, for our two sad-fated returnees from a life lived as one naively imagines it rightfully should be, nothing more than a prison of obligatory socioeconomic striving and a den of cheap thrills/temptations that can only sap the purity of their feeling, souring it to the point that any illusions about their love being extraordinarily strong are irreparably shattered. But their unarticulated (perhaps inarticulate) worldview may have had an insurmountable contradiction to begin with; it is, ultimately, the neon-lit world of the cinematheque and the dancehall, the same consumer/entertainment culture from which Monika first derived her ideas about a romance untainted by the urban day-to-day, to which she turns for sustenance after the tedium and hardship of nature, and which nurture her growing dissatisfaction with and ever-loudening complaints about the unromantic stability the weary Harry now feels obliged to provide for her and their infant daughter.

Made and released just before Smiles of a Summer Night and, especially, The Seventh Seal would make Bergman's name internationally, Summer with Monika, whose daringness now seems to spring as much from its distinctively serene, clear-eyed, lush, and confident stylistic strokes as from its brief, decidedly non-prurient glimpses of star Harriet Andersson's figure in various natural states of undress, is a progression on all fronts from Bergman's previous work, and the most identifiably " Bergmanesque" of his films to that point. The director and his incredibly gifted cinematographer, Gunnar Fischer (always unfortunately, if understandably, given short shrift in the face of Bergman's next long-running visual collaboration, with the even greater Sven Nykvist), really raise their collective bar here, and the film is replete with those odd, often discomfiting, yet perfect Bergman compositions, with the performers framed and directed in a way that allows them to be at once as iconographic as a still photo and yet remain dynamic and very much inside the film's sometimes oppressively intimate reality. Extreme close-ups of Andersson, sharing a luxuriantly sexy cigarette with Harry or, later on and even closer in, having a dejected one on her own as she seems to stare down the camera; moments where the lens seems to physically draw out emotions that would seem impossible to act with merely a facial expression; and, in the second of the film's neatly (but not too tidily) structured three parts, exterior shot after exterior shot (with the visual sense of open space through Bergman and Fischer's use of very wide-angle shots contrasting with the cramped, almost exclusively medium-to-close-shot spaces in the film's city-set sections) that employs the natural light in a way that plays such a huge part in Bergman's unique cinematic treatment of nature as something both alluring and foreboding; no joy seems as exhilarating, no emotional or physical agony more brutal, as when played out in a Bergman film against its literally awesome backdrop.

This visually emblazoned sense that we are in but not quite of Nature -- a crystallization of a familiar, eternal philosophical impasse -- runs through a great deal of Bergman's work, but here it has a particular melancholy to it deriving from that extended, blissful stretch after Monika and Harry's escape but before their return -- the portion of the film in which time, for the characters as for us, slows down and we're wrapped up in an alternatingly placid and savage gorgeousness not intruded upon by banal cares and worries; what can ever feel like real freedom and love again after that experience, whether or not it was doomed from the start by its refusal of harsh reality? Like Summer with Monika's finally socialized but ground-down and emotionally obliterated couple, we may wonder if a taste of that heaven is worth the purgatory of a civilization whose harshness can only seem much worse afterward and from which, ultimately, there is no real escape. Unlike them, however, we can say with confidence, from our vantage point as viewers for whom both the heaven and the purgatory Bergman so fluently creates here are different-flavored but equally succulent varieties of cinematic manna, that yes, indeed, it is very well worth it.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Criterion's digital restoration and transfer of the film -- AVC-encoded and mastered at 1080/24p, at its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.37:1 -- is a shimmeringly lovely thing, with barely a trace of flicker and virtually no debris, scratches, or other expected (and even, in older contexts, acceptable) signs of print wear or damage. The film's black-and-white contrasts are kept beautifully well-modulated, all the natural celluloid texture unscathed by digital noise reduction. A brilliant, conscientious transfer that gives the film its full due.

Sound:The film's audio is presented on an uncompressed PCM 1.0 monaural soundtrack (in Swedish with optional English subtitles) that renders every available nuance in the film's sound with clarity and full dimensionality; one can be confident that the film sounds as good and has as much fidelity to the source as possible.

Extras:--An introduction to the film by Ingmar Bergman (5 min.), with the filmmaker interviewed in 2003 by journalist Marie Nyrerod (from, apparently, the same sessions used for her feature documentary Bergman Island as well as other introductions like this one for other home-video releases of Bergman works). Bergman briefly describes his undying affection for Summer with Monika and is surprisingly forthcoming about the romance between himself and Harriet Andersson that first flared during the shoot.

--"Peter Cowie Interviews Harriet Andersson," a most congenial yet thorough and probing 28-minute discussion between Criterion's longstanding go-to Bergman expert and the still-going-strong Andersson, a charismatic, luminous presence in her graceful age who, 60 years on, has what seems a photographic memory of how she came to work with Bergman and what it (and he) was like. (If hearing any other Scandinavian notable you can think of speaking in their perfect English hasn't already stoked your envy of those nations' educational systems, it could very well be Andersson's fluency that gets you there.)

--Images from the Playground, 30 minutes of 9.5 mm footage made by Bergman on various movie shoots over his career, extracted from apparently extensive footage preserved by Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Foundation (Scorsese himself appears at the beginning here for a brief intro) and edited together by Bergman associate Stig Bjorkman. The bulk of this privileged, really beautiful window into Bergman's creative world is focused in particular on Harriet Andersson and Bibi Andersson, both frequently recurring actresses in Bergman's filmography (and both, in their time, Bergman paramours), each of whom has a section devoted exclusively to her. Audio is provided by new interviews with both Anderssons and by archival interviews with Bergman, often in a disarmingly candid, generous, jovial mode. (For all that, the biggest revelation here may be a quick glimpse of Gunnar Bjornstrand and Ingrid Thulin making each other laugh uncontrollably on the set of Bergman's magnificent, too often overlooked Winter Light, a film which itself contains not one a millisecond of levity.)

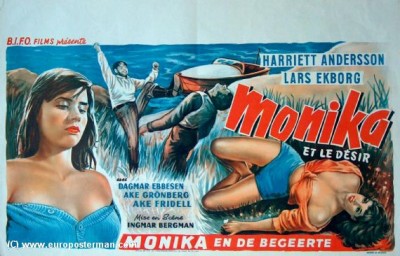

--"Monika Exploited!", a 12-minute piece in which author/exploitation film expert Eric Schaefer gives a brief overview of the history and workings of exploitation cinema before delving into American entrepreneur Kroger Babb's re-cut, re-dubbed, dubiously legal Stateside release of Summer with Monika as Monika: The Story of a Bad Girl, which Babb shamelessly marketed as pure titillating, sensationalistic fare.

--The film's elegant, narrator-less, title-free original theatrical trailer.

--A 30-page booklet featuring a new essay on the film by scholar Laura Hubner; a reprint of Jean-Luc Godard's famously admiring 1958 review of the film; and an "interview" conducted by Bergman with himself that was included in Svensk Filmindustri promotional materials upon the film's initial release.

An early feat of probing observation into human interrelationship and emotion in an oeuvre that would come to cast a very long shadow over the cinematic treatment of those matters, Bergman's Summer with Monika is an unsparing but not unpitying look at life as an arc from defiance to escape and freedom to inevitable submission in a world that grinds away the idyllic hopes of the young. But what beautiful hopes those are: for the stretch of the film in which its young lovers, Monika and Harry, are unburdened by workaday pressures, it looks and feels like life as it was meant to be lived, wild and free, and Bergman's oft-overlooked but all-important way of making sensuality come palpably alive on celluloid is there in its full, near-pagan force (sun and water never look as simultaneously elemental and aesthetic as they do in Bergman) as our young couple head out on their boat into the woods and the water, cutting themselves off from a callous civilization that's done their deepest feelings no favors. Equally powerful, though, is the film's tragic sense that any such attempt to make one's cinema and magazine-fed visions of living forever on love will sooner or later be dashed upon the rocks of practical necessity and the fearsome power of human inconstancy, and Bergman's well-known inability to flinch in the face of discomfiting, unfulfillable longing and interpersonal breakdown are here, too. It's a film Bergman probably couldn't have made after he grew older and became more sophisticated (in both the personal and artistic senses), but that's not to say that it's immature, just that it has more rawness, urgency, and unevenness to it than the later full-fledged masterpieces -- a less mediated take on the joys and pitfalls of emotions and their aftermath from someone not so much older when he made it than the film's very young (19 and 20) lovers, not so far away in his own affective experience from their very strong, very immediately and urgently felt, not very articulate desires. In the critical lexicon, "adolescent" and "romance" are terms not often meant kindly, but Summer with Monika is a welcome, gorgeous exception: it's both of those things in the best, most effectively touching and rousing way possible. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||