| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Woodmans, The

I had never heard of the photographer Francesca Woodman before watching The Woodmans, director C. Scott Willis's recent film about Woodman's life and that of her artistic family, whose own lives were permanently altered by her suicide at the age of 22. The fact is, the film may not even have existed without the Woodmans' story being marked by that sad, scarring event, and indeed, Francesca's work and her posthumous fame is one of the things about which the film is most incisive, evenhanded, informative, and involving. But that's not nearly the extent of its accomplishment. Willis so clearly and powerfully evokes the complexity of the multiple, enmeshed stories within this unusual (but also, in its dynamics and roles, very recognizable) family that it's hard to say which one of them the film is primarily about. That lack of a single principal "character" is a good thing; it makes for a multiplicity of stories that merge into one vibrant, life-filled whole, not a result of indecisiveness on the filmmakers' parts but instead an intentional structure that becomes an attestation to their skill, perceptiveness, and real curiosity and passion for their subject(s). Each of the very different family members seems in his or her own turn to be at its center, and the naturalness as we segue from one to the other -- the imperceptible shifts in emphases that just seem to flow from one to the next -- makes for an engrossing, affecting, and richly nuanced experience.

When George Woodman, a WASPish boy who came from money, met his wife, Betty, a middle-class New Yorker from a Russian Jewish family, what drew them together was their shared love for art and an aspiration to make their own. But as the couple (still together after a half-century of marriage) tells it, theirs were not identical but distinct, complementary approaches to their work: George was an abstract painter, Betty a sculptor who thought usefulness and beauty were synonymous and was thus disinterested in galleries, despite the philosophical underpinnings of her work. They struggled, living an unusually intellectual and "bohemian" life, and they brought up their children in a way many of us might envy: a very high value was placed on creativity in their house, with exposure to art and art-making of all sorts, a love of learning, and an openness toward the world as the most constant currents running through the kids' upbringing, encompassing experiences like yearly trips to Italy to take in and ponder the great masterworks (complete with individual notebooks in which Francesca and her brother, Charlie, were encouraged to put their drawings, thoughts, or any other articulation of their impressions). There was order (this isn't in the least a my-outrageous-artistic-parents-ruined-me tale) but enough freedom and space to think and decide for oneself in matters that really counted, and the Woodmans by all accounts did their best to balance their passion for their work with their real, visible love for their children.

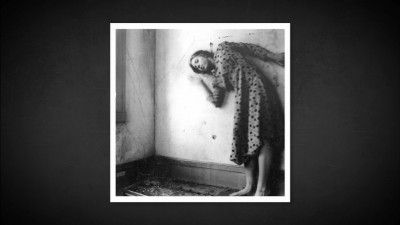

In several important ways, it was a privileged existence; the Woodman offspring were unusually liberated to explore and encouraged to strive for whatever it was they cared about, though it doesn't come as much of a surprise, given their parents' example, that both Charlie and Francesca decided that what they cared about was making art. As the film recounts through in-depth present-day interviews with George, Betty, and Charlie, the ambition to create that was in the air took particularly deep root in their daughter: as Charlie puts it, everyone in the Woodman household knew and embraced that they were "different" because of their vocational devotion to making more or less impractical art when all the other kids' dads went to an office ever day, but it was Francesca who felt and acted "special," with her eccentric behaviors and penchant for self-mythology flourishing after she was given a camera by George in her early teens. The teenaged shutterbug took to the medium immediately, creating fine, accomplished photographs, often nude self-portraits that were less sensual or objectifying in the erotic sense than provocative commentaries on the physicality between human beings/bodies and their environment whose intelligence was as striking as the palpable skill with which she created them. Various figures among the childhood friends and former classmates and colleagues of Francesca (whether from the boarding school she elected to attend instead of heading to Italy with her family, apparently as an adolescent strike toward removal from the parental sphere, or from the elite Rhode Island School of Design, the art college she attended) all relate their own experiences, via Willis's camera, of Francesca's relationships familial and romantic, and of her vacillations between preening confidence and vulnerability; between affectation and an abundantly clear, real, prodigious talent.

Their impressions of the photographer are confirmed through the film's intermittent excerpts from Francesca's troubled, poetically expressive diary and by good, long looks at her work, both in the making (she would often take videos of her process, which we see many clips from here, showing all the joyous immediacy of her working moments, however eerie or disturbing the intended outcome) and in their states of completion: here we have a woman who overthinks and defeats herself while always remaining absolutely certain of her gift and its worth (if nothing else) -- burning, bursting with the desire to show that she's good at what she's giving all the best of herself to and making some amazing art all the while. The extremities of self-assertion and self-laceration struck here create as true a documentary portrait as you've ever seen of the "artistic temperament" (whether or not Francesca's is particularly indicative of a "female artistic temperament" or not will be decided by each viewer, though one could make a strong claim for an identity-exploring feminist element in her work similar to that of Cindy Sherman, a fellow photographic artist who actually succeeded in all the ways Francesca wanted to) in which a passion for excellence, a need to create, and a more troubling but inseparable drive to be acknowledged all rub together to create that spark that transfigures inspired ideas into the frenzied work and persistence that make one an artist performing the physical and psychic labor that statistically probably will not, but always possibly just might, result in great work and glory.

The years without any real recognition or success took their toll on Francesca, who toiled as an underling in the world of photography and felt lost and failed, going in and out of therapy and on and off of medications until finally taking her own life by jumping off of the roof of a New York building. But the somber conclusion of Francesca's saga only brings us to about the two-thirds mark in The Woodmans, and that's where the film becomes not just a fascinating story about this now-renowned photographer but a larger, more multileveled, more ambiguous meditation; the fraught, traumatic Francesca episode is the Woodmans' and the film's second act, but they are given a third that both deeply connects with and progresses far beyond their loss. Before Francesca gets her camera, and then speckled throughout the Francesca-focused part of the film, the other Woodmans' work and lives are there in full force, too, occupying each one of them singularly even as their familial bonds cause all their lives to overlap: George's paintings, which he has tried and tried and mostly failed to get shown or even sold; Betty's pottery/sculpture, which she self-effacingly claims became so successful starting in the '70s because of an NYC art-world "fad for clay"; and Charlie's video/musical performances and installations (in something like the vein of Philip Glass's or Steve Reich's projects). Of course, as with any situation in which a child has committed suicide, there are ongoing consequences and undecidable factors, things that will never stop niggling and just have to be slogged through coped with, and Betty and George are very honest about all of that -- their ambivalence about their relationship to their daughter and her work in ways that run the gamut from the unavoidable influence of the event on their own work to the strangeness of being executors of her estate and therefore her commercial agents to the stretches of time in which self-doubt/guilt and self-forgiveness battle it out in them over what caused their daughter's emotional difficulties and suicide. These things are all mulled in a refreshingly clear, emotional, but never showily dramatic way by the ones Francesca left behind, creating portraits of each of them as individuals of a depth, intelligence, and singularity of articulation well worth our attention.

But another, perhaps less familiar ambivalence (one that runs concurrently throughout their marriage, their child rearing, the suicide, and beyond) that the film captures beautifully, aided by this gentle forthrightness on the part of Betty, George, and Charlie, has to do with the competitiveness of artists. That inability to disregard others' success and avoid measuring it against one's own (or lack thereof) is certainly observable in the cutthroat New York gallery/museum world, whose backstabbing and impenetrability may also have been a factor in Francesca's overwhelming depression and neurosis. But it's also suggested that Francesca's natural competitiveness was exacerbated by her family situation and the need to distinguish herself from (and possibly outdo) her parents; that competitive streak would surely be a much more uncomfortable and unspoken subject inside a family such as the Woodmans, where everyone's ambitions demand a slice of recognition from the same, none-too-large audience. As we can discern here, those already tangling factors in the family ties expand exponentially when one member's death skyrockets her to a fame she may not otherwise have had, further twisting emotions into inscrutable shapes and bringing up a million clashing feelings as one's own work and recognition become closely and permanently linked with the dubious celebrity of a suicide. But the tentative grace with which the Woodmans navigate their ongoing emotional stormy weather is worthy of the word "inspiring," despite its redolence (not at all applicable to The Woodmans) of homilies and pat, cheerful answers to pain and problems of lingering depth. Both through their engagement with Willis's questions and their ponderings of questions they've been asking themselves for decades, the film gives us ample opportunity to witness both the Woodmans' grief and their resilience, never "getting over" but gradually incorporating their bitter loss and its far-ranging implications into lives that they obviously believe need to go on. Even more happily indicative of their embrace of life despite everything is the survival of their unflagging need to create: Charlie continues to make art in his own way and in his own time, brushing away the dogs of sibling rivalry nipping at his heels; George has himself taken up photography, making pictures that contemplate and even critique their inherent relationship with those of his late daughter; and Betty is shown working on and beamingly presenting a commissioned piece for the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. They smile at times and are anguished at others, and we are privileged to see and be moved by the well-expressed range of their thoughts and emotions over the course of Willis's interviews and footage of them in their earlier lives and while at work.

Art that's worth dying for, art that makes life worth living: The film sheds bounteous light on both, what it looks and feels like to make one or the other and what the results can be, without ever slanting the illumination in one direction or another and without ever offering its own preferences for this or that mode of expression among the different Woodmans' very distinct, even contradictory ways of making art. Mention has to be made of the simple, careful restraint of Willis; his videographer, Neil Barnett; and the film's editor, Jeff Werner, all of whose work dovetails into a portrait whose multiple facets gleam and enhance each other in a way that makes the film glow; this team's work in the medium of cinema has an artistry of its own whose results are pleasing to look at and have a careful, well-honed structure and symmetry, making for a genuinely piercing but never exploitative or easy contemplation of their subjects. But it's ultimately the subjects themselves (and I'm sure the filmmakers would agree) whose willingness to participate and generous sharing of their experience make the film such a seemingly simple yet finally profound revelation.

THE DVD:

The film, presented anamorphically at an aspect ratio of 1.78:1 (misidentified on the box label as 1.85:1) consists mostly of present-day digital video footage and several primitive, blurry videotapes made by Francesca Woodman as she took her photographs. All of the footage looks just as it should, with Francesca's footage bearing the mark of its technologically long-ago time and the newer high-def video looking clear, clean, and vivid. The transfer is an excellent one all around, with no compression artifacts or any other video flaws.

Sound:The Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo soundtrack delivers the film's well-put-together sound very well, retaining all the above-average care taken in the interview recording and mixing to give us a full, rich sound with no imbalance or distortion whatsoever.

Extras:None.

A humane art-world documentary that dispenses entirely with any glitz or gossip and goes straight for the tougher, more resonant, more meaningful human and creative dimensions, C. Scott Willis's The Woodmans ably and precisely performs an intimidating balancing act between its real, venerating respect for artistic impulses, enterprises, and personalities and its insight-enabling perspective revealing how very human in all ways (good, bad, or ambivalent) artists can be. Its recounting of one creative family's tragedy -- the suicide of a very gifted, self-mythologizing, ambitious photographer, who was their daughter and sister -- in terms that rigorously hew to gathering the testimony, exploring the work, and recounting their lives with no trace of imposed judgment allows us to interpret their story for ourselves, with no influence other than the family's often beautifully recounted or documented memories, impressions, and current lives. Willis's film is thorough and well-researched, but not academic; celebratory without whitewashing; and optimistic without being naive. It is a quiet, lucid, yet incredibly moving (about, it should be said, unusually thoughtful, lucid, and, yes, ultimately very moving subjects) reaffirmation of the value in the blood, sweat, and tears of being an artist. At the same time, it also asks good, serious questions about what particular sacrifices an artist (and their family) makes, and how necessary those sacrifices may or may not be, when deciding to devote their life to that intense, sometimes very difficult and draining, urgent and indispensable vocation. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||