| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

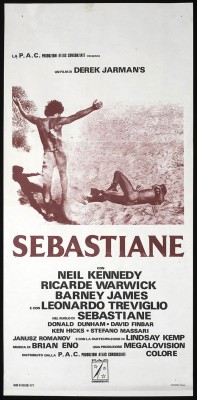

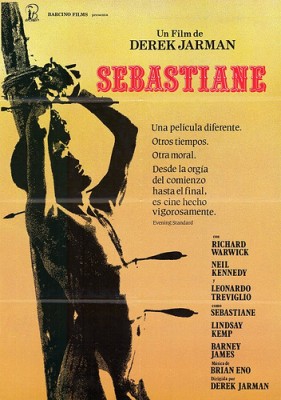

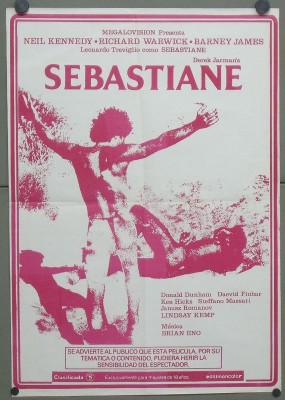

Sebastiane: Remastered Edition

"Yet each man kills the thing he loves...." - Oscar Wilde

Thanks to the enduring canvases of the Christian martyr St. Sebastian by early 17th-century painter Guido Reni (along with the countless others who have also painted Sebastian over the centuries as a perfect specimen of youthful masculinity, as sexy as he is sad), the saint has become more prominent as the most famous example ever of homoeroticism in art than any kind of religious icon, his barely-clothed binding and assassination by flying arrows usually inspiring, oddly enough, a depiction as a posed-and-flexed hunk whose deadly piercings seem to make for a peculiarly ecstatic death. It's a paradoxical and intriguing art-historical blurring of the lines between innocence and lust, the cerebral/contemplative and the erogenous, the sacred and the profane, that seems tailor-made for a filmmaker like Derek Jarman, the late British king of the proudly queer cinematic avant-garde and himself a blurrer of the lines between classicism and modernism, to use as the jumping-off point for his debut feature. And so it happened that in 1976, exploding up from an underground long thoroughly accustomed to gayness, out into a wider world experiencing the newly outspoken, public gay liberation movement as an astringent shock, came Jarman's first feature, Sebastiane, at once a considered, intelligent, and serious meditation on its subject and theme by a contemporary artist paying obeisance to a tradition he's simultaneously questioning and redefining, and an earnest celebration of eroticized masculinity on film unrivaled before or since.

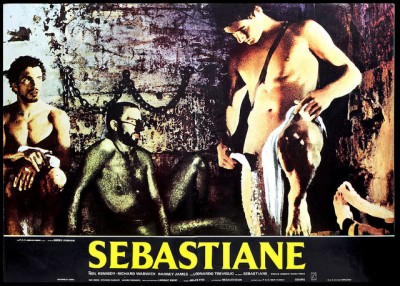

Jarman opens Sebastiane as if it were an educational history/period film, with a crawl of text over a faux-Roman drawing (by production designer extraordinaire Christopher Hobbs) informing us of the facts of Sebastian's life: a court favorite of the third-century Roman emperor Diocletian, he was persecuted, exiled, and murdered for showing inappropriate empathy for, and then becoming one of, Rome's favorite persecutable minority, the Christians. But when we then cut to the film's first scene of action, in which we ultimately witness the obligatory exposition -- Sebastian's (Leonardo Treviglio) expression of sympathy toward a murdered Christian in the presence of Diocletian, and the emperor's excommunication of the handsome young man from his court and out into the desert with a group of Roman miscreants under the watch of his soldier Severus (Barney James) -- we're in the first of what would become, over the director's filmography, a long run of peculiarly Jarmanesque, playful yet disorienting anachronisms: Diocletian's court is a glittered-up, post-Bowie/pre-punk '70s orgy of androgyny, decadence, and a sexually provocative performance-art dance troupe that does an outrageously camp/obscene all-male number in which a near-nude figure with face and body so ornamentally made-up as to appear near-reptilian (a figure copied meticulously for one of the glam-rock production numbers in Todd Haynes's Velvet Goldmine) is pretend-surrounded, attacked, and defeated, to his delight, by masked men bearing exaggerated phalluses, making for a sort of premonition/travesty of the later, ultra-sexualized scourging and martyrdom of Sebastian himself, a detailed rendition of which the film then takes us out under the gorgeous, merciless Sardinian sun to convey through its lingering, obviously aroused gaze. (Even out in the more timeless desert and away from the court, there will be slyly anachronistic references, in the film's historically accurate spoken-Latin dialogue, to Fellini Satyricon and Cecil B. DeMille).

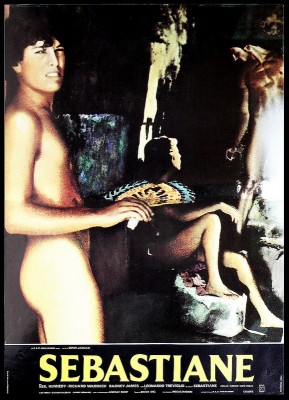

The Christian, pacifist Sebastian is an object of ridicule for the group of men in whose exiled, isolated, sexually frustrated company he finds himself at this distant desert outpost, not least because he refuses out of principle to participate in the warlike maneuvers and drills Severus leads daily. Whether through homophobic protesting-too-much denial or open indulgence, the men, naked and basking in the sun and frolicking together in the nearby lake, are perpetually obsessed with one another's amorous availability, which manifests in sexually loaded, frat-like teasing and taunting for the most part; in the pairing off of the older Anthony (Janusz Romanov) and the younger Adrian (Ken Hicks) (a socially acceptable coupling on Roman terms in a way two men of the same age falling in love would not have been); and, most repressed and murderous, Severus's clear, agonizing attraction to Sebastian, which, as the enforcer of the Roman law Sebastian has found himself on the wrong side of, and as an authority figure who can't afford to indulge in the way his men do with each other lest he taint his aura, Severus must vanquish at all costs. That means disproportionately harsh persecution and quasi-S&M punishment of Sebastian by the tormented soldier, from which Sebastian's friend/ally/confidant, Justin (Richard Warwick), cannot protect him, and it eventually -- once the brutal Severus finally breaks down and begs Sebastian for his love, only to be refused by his victim -- leads to Sebastian's murder at the hands of the entire group of men -- an exorcism of his disconcerting, enviable beauty, a scapegoating in which even Justin is literally forced to participate. It's the Billy Budd cultural motif, the same one Claire Denis would transform into a masterpiece with a very different style but a near-identical story and theme in her 1999 film Beau Travail: unmistakable, undeniable male beauty disrupting a repressed, violent, fragile macho regime and paying the price, Christ-like, for their fear and shame.

The film's litmus test will surely always be the extended, tantalizing slow-motion scene -- the centerpiece of the picture, in a way -- of Anthony and Adrian off alone and play-wrestling nude in the lake, an encounter looked upon with teeth-gnashing envy by Severus, who must deny himself such pleasures. If most dutifully realistic, sterile actual pornography fails completely to replicate the rhythms and focuses of our sexual fantasies, this scene luxuriates in the physiques and their interaction in a way more familiar from such reveries; the dead-serious, unabashedly erotic motivation and intensity of the sequence has few rivals in the cinema (Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie in Don't Look Now might be one alternate example, Naomi Watts and Laura Harring in Mulholland Drive another, though this achieves and sustains it much more intently and thoroughly), and has often, with some reason, been characterized as gay erotica. But that's only partly true: It really doesn't depend upon one's own erotic response to naked men; the filmmaking itself, here and throughout, is so tactile (whether it's Peter Middleton's cinematography, with its epic desert-landscape vistas caught on 16 mm for an unexpected, bracingly intimate texture or, in this particular moment, the slo-mo, water, and synthesized sound effects recalling the famous slow motion scene Kubrick created in A Clockwork Orange), the photography so immediately present and beautifully rendered, that if you love cinema, whether or not the moment does anything for you below the neck, your eyes and ears won't want to or be capable of resisting such a ravishing deployment of the medium.

There's an undertone of melancholy infused into the film's every frame of sun-drenched eroticism (the inseparability of the sex and death drives in the cult of St. Sebastian, which Jarman is quite well aware of, matches Freud's troubling but very difficult to disprove claims on the matter), enhanced greatly by the use of Brian Eno's stirring ambient music and the general impossibility for real-life manifestation when it comes to the most often thwarted, forbidden desires that course through the film and gives it its spark and tension, its feel of erotic delirium and idealized, inconsolably fleeting dream. It is a dream that the film finally, disturbingly and movingly wakes up from in its final moments, with a radical cut to a static tableau, shot from the blurred, flattened-out point of view of the dying Sebastian, of his objectifiers, persecutors, admirers, and murderers. This startling maneuver alters everything that came before it, turning the tables on us like Raymond Burr did on James Stewart in Rear Window and demanding that we ponder where exactly we stand in relation to, and what we want from, the martyred figure(s) we and the film have voyeuristically and joyously but perhaps not innocently delectated in objectifying. It's a brilliant flourish that cements the film as not just a memorably sensuous experience, but resonantly thought-provoking, as well. The culminating impression of Sebastiane is that it is arousing and haunting, haunting because it has aroused through what it ultimately calls into question, the subjectivity and objectification seemingly endemic to the movie camera; for a film perhaps best known as a kind of soft-core gay porn, it's a remarkably relevant, accomplished work of art that comes full circle, offering us a lavishly erotic fantasy for which it makes no apologies, but at the same time insistently asking profound questions, not easily answerable, about the intersection of fantasy, art, desire, and power that is nowhere more immediately discernible than when it happens between us, seated in the dark, and the images writ large on a silver screen.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The video -- presenting the film in an AVC/MPEG4-encoded, 1080p-mastered transfer with an aspect ratio of approximately 1.66:1 -- reflects the quality of the source materials, which, as usual for Jarman's movies, were created low-budget on 16 mm, blown up, and circulated without much care for their future preservation. There are a number of spots of slight print wear/flicker, visual pops, and scratches, but it has been cleaned up quite a bit since the last time I saw it on home video, and it's likely that this is the best it's ever looked since the first brand-new print was screened. If it might have been possible to do a bit more cleanup/restoration, the PQ is still quite good overall, and one is grateful that Kino has erred on this side instead of going for an all-out DNR scrubbing; the grain and texture is all-important for this film, and that has been left intact, preserving Sebastiane's rightful air of tactile sensuality emblazoned upon celluloid.

Sound:The film's mono sound, presented here on a PCM 2.0 soundtrack, is also a tad rough, but certainly not distracting to an insurmountable degree. There are rare and intermittent pops, bumps, and scratches, as well as a couple of noticeable stretches of crackle. There's also a sort of lo-fi-ness to the sound on the whole, most noticeable in the moments when Eno's music is present, that seems likely to be in large part endemic to the source rather than an oversight on the part of the Blu-ray authors. Overall, a more than decent representation of the film as it actually sounds, which was never meant to be at a technologically state of the art level.

Extras:None.

Less a filmed version of a Guido Reni canvas than some inebriating, audacious blurring of the lines dividing avant-garde underground rawness from the composed, Kubrickian cerebral (as well as the ones that heretofore distinguished melodramatic historical epic from languorous gay-skin-mag eroticism), Derek Jarman's Sebastiane is a glorious debut feature from one of the most unique, provocative, and divisive art-film sensibilities of the last century. The story it tells is inspired by the one behind the countless paintings of the titular Christian saint's martyrdom -- a longstanding symbol of fetishistically detailed male beauty -- and Jarman did train as a painter, but these pictures are more vivants than tableaux, and Jarman uses everything he can -- the brilliant sunlight of the film's Sardinian location, slow motion, the sounds of wind and water, Brian Eno's savage-breast-calming music -- to heighten the living, breathing physicality-in-motion potential of his scenario, to render tangible and overpowering the ecstasy and pain, the respirations and pumping of blood in what he's depicting. It's intellectual and lusty, with a tone that's like fire meeting ice (or the Dionysian seductively luring the Apollonian off its pedestal, if you want to get Jarmanically classicist about it), topped off by a coda that breaks the spell and sheds the film's eroticism for transcendence, in one of the most breathtaking acts of empathy a filmmaker has ever performed with a camera.

Sebastiane is, willfully and famously, jam-packed with fit, naked men whose every attribute Jarman unabashedly admires and celebrates, but by now it would just be tiresome (not to mention inaccurate) to ghettoize it as properly, deeply enjoyed only by heterosexual women and homosexual men. If you take it in without hang-ups or insecurities, it is a rich pleasure no matter who you are, whether Jarman's lyrical, tender, ultimately melancholy cinematic raptures over well-proportioned male forms, alone and in frolic -- which go beyond merely explicit or pornographic (there's not a single sex act depicted in the film, after all) to the truly sensuous, in the way only film can be sensuous -- are actually candy for your libido or not. The intensity of desire, parlayed as it is here not into exploitation but exquisiteness of artistry, should taste just as sweet and offer aesthetic pleasures equally profound for the cinephilically-minded of all orientations. Both sexuality and the medium of film get garbled by simplistic definitions and shaky presumptions in our culture, too often having their real attributes and possibilities suppressed in the process, which is why it's still too early for a film like Sebastiane to be judged on the same terms as the blatantly "homoerotic" masterworks in the supposedly finer arts that everyone's been admiring without panic for centuries, from Michelangelo's statue of David to all those nearly-nude paintings of Sebastian himself. At least the film has now been given new, restored life on Blu-ray, so that when the dust finally settles and we've all grown up (let it be soon), Sebastiane will come into its own as a work of classic, classical, relevant erotic art that can and should be admired by everyone. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||