| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

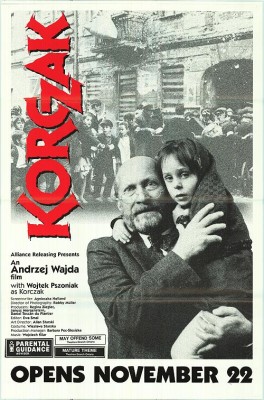

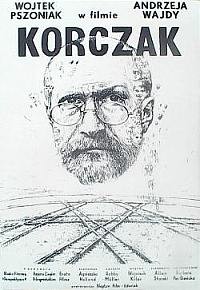

Korczak: Kino Classics Remastered Edition

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional and other sources, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

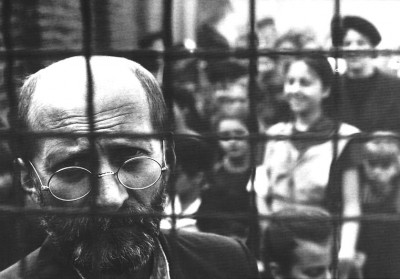

Henryk Goldszmit, who publicly went by the pseudonym Janusz Korczak, was a Polish pediatrician and something of a celebrity, an expert on children and child-rearing who dispensed knowledgeable advice in print and on the radio. He was also one of those very unusual, near-unbelievable souls who actually devoted his entire life, tirelessly and selflessly, to "the children," both in general as an educator, author, and radio speaker and in his every other waking moment as the head of a Warsaw orphanage for Jewish children. In Andrzej Wajda's (Danton, Ashes and Diamonds) 1990 biopic Korczak, we first meet the doctor framed in an intimate close-up, speaking into the microphone in a sound booth as he admonishes his radio audience not to believe in the myth of the noble person who makes sacrifices: some men have cards, others have women, and he's interested in the well-being of children. He thus characterizes his unfailing devotion to the 200 orphans in his charge as nothing but a gratifying hobby or enthusiasm he happens to have, and that entirely unsentimental view of Korczak and his humble, self-effacing, but undeniably impressive humanitarianism is one the film does its best to share. But even in just relating the bare facts of his life as he tries to do right by "his" children in the pre-WWII horror years of rising European fascism, anti-Semitism, the Warsaw Ghetto, and deportation/extermination, the film can't help itself giving us a picture of him as a captivating, fascinating, inspiring figure. The facts speak for themselves, and what they tell is the honest, unforced story of a Jewish hero and Holocaust martyr who would have been bemused at best to know a movie would one day be devoted to what he refused to see as the exceptional service and fortitude that were the markers of his rare grace as a human being.

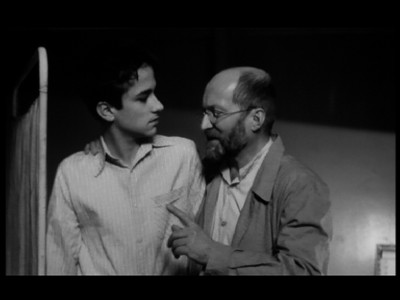

Polish actor Wojciech Pszoniak (Robespieere in Danton) turns in a brilliant performance -- the film's linchpin -- as the late-middle-aged but vibrant Korczak, giving him a businesslike, down-to-earth physical presence and demeanor of forward-moving practicality from which his tenderness and steadfast morality emanate in actions much more than words. ("I have no dignity," he bluntly tells a group of idealistic young Jewish rebels taking him to task for his acceptance of black-market racketeers' donations to help his starving children, but his indefatigable labor and advocacy, his willingness to lower himself for the good of the orphans, and his very body language all belie such self-deprecation.) He is a person who sincerely wants to be of service, and although his world, as a Jew in Warsaw in the late 1930s, is already visibly closing in around him -- with the clearest signs including graduated orphans telling him of the anti-Semitic violence and vandalism they're increasingly experiencing and his own polite, excuse-offering, spineless firing from the radio program because "his person is causing problems" (with the German occupiers/authorities) -- he refuses multiple entreaties from friends to flee to safety, perhaps to the Palestinian homeland or America, because he will not for any reason abandon his children just to preserve himself. Things get worse, of course, with the removal of Korczak and the kids from their utopian-socialist "Our Home" orphanage/school compound/healthy outdoor grounds to the grimy ghetto and its impending starvation, dead bodies in the streets, black marketeering, waffling from the supposed Jewish intermediaries between the ghetto and the Nazis, and the spectre of deportation and mass-murdering genocide that is murmured about but comes most starkly in the form of a chilling, brilliantly executed scene in which an escapee frantically wanders the abandoned ghetto streets screaming the warning at the top of his lungs, climbing a tower to announce their grim fate to the ghetto Jews only to be shot down by the patrolling Germans. Korczak's attempts to keep his huge family alive and afloat in the ghetto is the perpetually engaging and intriguing "plot" of Korczak -- a story we all know perhaps too well (familiarity breeds complacency, if not contempt) told from the point of view of someone who won't let himself get caught up by the exigencies of a crisis mounting all around him, because his sole objective is to preserve the human beings he's taken responsibility for at absolutely any cost. That is, tragically, a sacrifice he is ultimately forced to make, along with the children, all of whom were killed along with Korczak in 1942 at the Treblinka extermination camp.

Rounding out the largest portion of the film, which takes place between the orphanage's ghettoization and finally its deportation, Wajda and the film's screenwriter, Agnieszka Holland (who channeled her interest in telling stories of the Holocaust as experienced in her native Poland into her own career as an auteur, helming 1991's Europa, Europa and last year's In Darkness), do abide, where they can, by Korczak's decentering of himself in his life, doing just what he would have done, making the film to the fullest extent possible as much about the children as him. The little urgencies of childhood -- an adolescent's falling in love with a Polish Catholic girl and suffering the inevitable (if not always, then certainly at this time and place) rejection, forced upon the girl and himself, for being a Jew; the taking under Korczak's wing of a boy whose mother is dying, who would rather have died with her, and who acts disruptively in the orphanage despite the loving care he's found there, etc. -- as well as the ins and outs of life as Korczak has organized it for the children, according to his progressive (no corporal punishment) principles as a pediatric expert are given their full due, so we're offered some inkling of what their lives would be like without the unwelcome intrusion of war and persecution. This focus on the amazingly resilient will to just live one's life, which always has enough unfulfilled needs and desires and problems of its own, allows Wajda and Holland to underline at the same time, without any romanticizing overemphasis, the overwhelming sadness of kids just trying to maintain the challenges, struggles, and routines of ordinary life in an environment where their "father" is doing his best to isolate and insulate them from rapidly encroaching horror, but where nobody can hide from the detailed, thorough, assembly-line efficiency of the Nazis' hate.

There's a moment at which I thought Wajda had perhaps gone too far in reflecting Korczak's stubbornly, naïvely humanistic, child-centered view of life, when the aforementioned boy who loses his mother is shown in a brief countershot, from Korczak's point of view in the face of a child's suffering he cannot ameliorate, to have a halo over his head. It fades away as quickly and suddenly as it appeared, and it's the only such moment in the film, but it reminded me that this new Blu-ray edition of Korczak comes emblazoned with a huge quote from Steven Spielberg on the cover proclaiming that "Korczak is one of the most important European pictures about the Holocaust." I find Schindler's List irretrievably problematic, and I wondered, is this halo moment Wajda's precursor to that cheesy little girl in the red dress that Spielberg concocted to wander through his Hollywood Holocaust? But no, this isn't a gimmick; it's a self-limited, momentary glimpse through Korczak's eyes, an effective and explicitly subjective visual signifier of the principal character's mindset, much better-integrated into a film that is on the whole honest and honorable, in a way Spielberg couldn't be even though he obviously wanted to, when it comes to the extremely treacherous terrain of representing the Holocaust in a dramatic/storytelling mode. Korczak also prefigures Schindler's List by being shot in black-and-white, but again, it feels less like a superimposed "device" than the best-suited choice for the story, with the subtle working in of the Germans' constant filming of the Ghetto as another mitigating factor; scenes in which Korczak is wandering past the starvation, poverty, fear, and death with a movie camera pointing toward the action from the foreground (i.e., closest to us and from our point of view) contain some of the film's most striking, haunting, and meaningful images.

Wajda's choice for artist best-suited to create for him a visual tone at once immediate and intentionally, aptly anachronistic is cinematographer Robby Müller (no stranger to working B&W miracles, as anyone who's seen Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man or Down by Law can verify), and it's proven to be a very wise one; there is almost no music (though the Wagner-referencing score by Wojciech Kilar is very effective and memorable as little bursts of aural punctuation, and in the heaving, queasy aural undertow it provides through the film's devastating closing sequence), and it is the visual dimension of Korczak that really accents, grants life to, and brings home Holland's scenario and Wajda's realization. It gives the film all the tone, all the emotional perspective it needs: the way Müller lights, frames, and travels through Wajda's blockings and compositions is very rich, somehow seamlessly seguing from an almost documentary-realist, snapshot look to a starkly elegant, white-heavy, mirrored elegance as required, evoking a time and place where movies almost exclusively existed in black-and-white, and bringing us as close as possible to the world as it looked, felt, and smelled to Korczak, his children, and their persecuted fellow residents in that atrocious ghetto.

The potential sin Korczak most scrupulously evades is using the Holocaust as an excuse for movieland optimism, trivializing it by offering false hope or an ahistorical feeling of "thank goodness we learned that lesson a long time ago." Hope was not on hand in Nazi-controlled Europe, which was much more The Grey Zone than Schindler's List: The net was extremely tight, hatred and indifference were widespread and dominant among all European gentiles, and statistically very, very few Jews who found themselves imprisoned by the Nazis were able to survive. Korczak and his 200 kids were certainly not among the survivors, and the film doesn't sugarcoat the tragic nature of its story; even though we're given a closing fantasy depicting a train car, the one into which Korczak and his children were herded like animals, miraculously cut loose and stalled, framed in a heavenly-lit exterior and opening in slow motion to allow its inhabitants to emerge and march freely forward into an open, idyllically sun-drenched field, this scene is bluntly concluded, and the fact that it's a fantasy called harrowing attention to, by the terse ending titles upon which the film closes: "Korczak died with his children in the gas chambers of Treblinka in 1942." Wajda and Holland are intelligent and respectful enough to know that no amount of optimism, imagination, or movie magic has any power to explain or reassure us about the horrors of still-recent history. To pretend otherwise would be false and cruel, and though Korczak pays tribute to a uniquely indomitable, kind, and good spirit, their final juxtaposition of the lyrical, beautiful capability of the movie camera to transform irredeemable history into what it should have been with the painful admission/acknowledgment of the severe limitations of that capability -- its utter inability to mitigate the needless extinguishing of that spirit, the best it can hope for being to serve as a sobering reminder -- is as fitting a conclusion as any imaginable.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The AVC/MPEG4, 1080p transfer, presenting the film at its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.66:1, is quite nicely done. Robby Müller's black-and-white cinematography is one of the film's main stars, and it's very well preserved here, with only two near-invisible instances of a small print scratch at a couple of random points (which don't distract at all in this context; nobody's gone so far as to artificially rough up the image, but the film is clearly meant to have a slightly antiquated look). Blacks are solid, the all-important contrast pops beautifully, and skin tones look natural, with nary a trace of any compression artifacts. The best part: The transfer's authors have deployed DNR, if at all, very conscientiously; I thought I detected one or two over-smoothed moments, but these things are subjective, and for the most part, the vital celluloid texture that makes the moving pictures actually appear to move on your home screen has been left intact.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono soundtrack is a perfect replication of the film's sound, which in its turn is a perfect replication of movie audio from a bygone era -- the late '30s/early '40s, to be exact. The dialogue is all clear, and the sparely-used music (in the form of Wojciech Kilar's haunting score) has an additional layer of troubled mournfulness to it deriving from its limitation to a single channel. From the first moment to the end, the film sounds exactly as it was clearly meant to; way the sound has been does full justice to the filmmakers' intentions.

Extras:The film's original (Polish) theatrical trailer is a good, succinct, intriguing example of the art of the trailer, but other than that and the accompanying small stills gallery, not much has been included in the way of extras.

In Janusz Korczak, director Andrzej Wajda and writer Agnieszka Holland have found a Holocaust hero/martyr whose persistence, dedication, and loyalty -- characteristics that actor Wojciech Pszoniak burns onto the screen with his committed embodiment of the man -- are as moving and extraordinary as their ultimate powerlessness to save him or the orphans in his charge is tragic. Through the graces of cinematographer Robby Müller's impressively diverse, detailed neo-Neorealist black-and-white cinematography (which looks fantastic on this newly remastered Blu-ray edition), Wajda and Holland's period film approximates a film of the period, adding an extra boost to its ability to isolate a specific historical figure in a particular place and time and make his story live with a certain immediacy. Korczak himself was a pragmatic, be-here-now type allergic to pedestals, and everyone involved in Korczak -- from the actors, Wajda, Holland, and Müller on down -- avoid any of the grandstanding or sentimentality that the doctor himself would have (rightly) found distasteful, instead honestly giving us a happy, hopeful character without feeling the need to make a happy and/or hopeful film out of his tragic story (happiness and hopefulness being the counts on which Life is Beautiful and Schindler's List, respectively, fall far short of the relevance and integrity Wajda and Holland more mindfully attain). Korczak does conclude before depicting the atrocities to which Korczak and his 200 orphaned children ultimately fell victim, but it's not out of timidity; the priority here is the increasingly difficult, pointless but necessary hanging on to as much normal life as they can that the doctor and the children go through, so that when they're rounded up and shipped away to the death camps at the end, we know in a more specific and deep way the lives that are now to be so callously extinguished.

The film's approach is to immerse us in the brave, awe-inspiring persistence of its characters, whose courage, resilience, and sheer humanity (whether it's the doctor's amazing loyalty to and selflessness toward the children to whom he feels responsible or the innocent, forthright living of life that the children continue to be capable of under the most hopeless, extreme circumstances) are captivating and admirable, while remaining respectful enough of the horror being depicted to acknowledge that none of that meant anything to tho leaders, armies, and nations intent on destroying them and all European Jews -- the genocidal regimes whose degree of success remains a stain on human history that implicates all of us in a way that can lead to deeply uncomfortable doubts, ones we might prefer not to dwell on, about the human race, history, and "progress." Korczak doesn't make any pointless, false attempts to mitigate those doubts or scrounge ignobly for something reassuring in the unimaginable, wrenching human slaughterhouse of the Warsaw Ghetto; it remains faithful to Korczak's goodness but doesn't pretend that his heroism, martyrdom, and doing the right thing somehow amounted to anything more than a noble, doomed delaying of what dehumanizing, efficient Nazi mercilessness made virtually inevitable. The truthfulness and respect Wajda and Holland adhere to demand not softening the indifferently cruel, irredeemable end the doctor and his loved ones met, the mass murders that made a mockery of their stubborn will to live, their lives' value, and the right of every human being to live unmolested by hatred and violence. If, as is my conviction, any honorable film proposing to represent the murderous Nazi persecution of the Jews is obligated to devastate in some way -- to ultimately avoid turning away or blinking in the face of the no-way-out futility and despair at the core of an episode in our history so shameful that it actually should traumatize us, if we are genuinely considering it in any meaningful way -- then Korczak can legitimately be considered such a powerful, honorably and conscientiously devastating reminder of a story that, hard as it is to take and near-impossible as it is to understand or cope with, must never be forgotten. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||