| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Lonesome: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials, not the Blu-ray edition under review.

"Gee, it's funny how lonesome a fella can be, especially with a million people around him."

The new Criterion Blu-ray edition of Paul Fejos's splendiferous 1928 color/B&W, silent/talkie Hollywood hybrid Lonesome is the kind of thing that makes you extra-happy to be alive at a time when such less-famous classics are finding new life (and much greater accessibility) on disc. It's a most welcome act of cinematic archaeology, affording all of us the opportunity to rediscover a rare and glimmering cinematic relic that's so fresh and alive, it feels like it's being made spontaneously, moment by inspired moment, as you watch it; the title alone is unusually evocative, like the name of a particularly poignant love song, promising something with a certain elusive depth and poetry, and the picture lives up to that and then some. Fejos gives us a romantic odyssey whose innocence is genuine and whose through-and-through sweetness is divine and authentic, never saccharine. But like Chaplin's Modern Times (to which it doesn't actually bear many other resemblances), Lonesome's rush of incredibly touching urban romance is derived from a troubled, critical attitude toward the way we live. If mechanization, dehumanization, and alienated labor were the serious fodder for Chaplin's indelibly charming and creative Depression-era shenanigans, then Lonesome, which is set in New York just at the delirious pre-crash heights of the late '20s, proceeds from the even broader, deeper-running paradox that, judging from the film's treatment of it, weighed just as heavily at the time of switchboards and streetcars than it is in the Internet/iPhone age: the fact that the more millions of people you cram into the high-rises of densely populated urban blocks, the more isolated, alone, lost, and sad -- "lonesome" -- each of those people is apt to be.

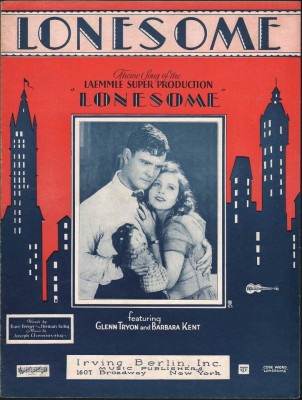

Like many of the best contemporaneous films (Sunrise, The Crowd -- it's a huge list, when you mentally survey the late '20s) bursting with the visual liveliness and creative possibilities afforded by the silent cinema, Lonesome has an exceedingly simple story, with not all that much more plot than the virtually non-narrative "city symphony" movies also being made at the time (People on Sunday, Man with a Movie Camera). Jim (Glenn Tryon) and Mary (Barbara Kent) are two twentysomething wage slaves working and surviving in New York City's late-'20s hustle and bustle. It's midsummer-hot in their small, non-air-conditioned apartments and in the sardine-tin subway cars, and they both drag themselves out of bed (she reluctantly but on time, he in a mad dash, as he has mis-set his alarm clock) for the last workday, he at parts-manufacturing factory, she as a telephone switchboard operator, before the Fourth of July holiday. That's the entire first quarter of a short-ish film (running time 69 minutes), but it zips by, with Jim and Mary's workday related through a smorgasbord of the kind of impressionistic imagery and non-linear editing-room adventurousness that so often makes silent-era films seem more dynamic, more visual, than a great many of the talkies that would follow, up to and including our present-day offerings. A lively tableau of Jim's and Mary's morning routine gives way to the numbers of a clock face framing the jostling juxtapositions and superimpositions in the image as a swarm of heads gabbing into telephones surrounds the feverishly connecting/reconnecting Mary; the camera shows us Jim at his metronomically repetitive task, punching out plastic parts, in a view from the inside of his machine that makes him look small and trapped, before cutting back into a gliding track-in/rack focus over his shoulder for a close-up revealing that his station is attached to a counting machine that relentlessly measures his productivity. The numbers, the calls, the minutes rack up until they're free, and then, as an intertitle informs us, it's "...a holiday!" After restlessly pacing his little room, Jim finally decides to join the festivities; he rejects an offer to be the third wheel with a buddy and his girlfriend, bluffing nonchalance and making up a story about a nonexistent date and merging with the crowd headed for Coney Island. Mary has made similar excuses to her friends and decided on the same plan, and it's on one of the vehicles transporting groups to the famous amusement park that Jim spots Mary.

Most of the rest of the film takes place on the beach and at the film's wondrous simulation of Coney Island, which has very little to do with the actual Coney Island (more on that in a moment). The flirtation, introduction, and sparks of romance between Jim and Mary as they fall in love constitute most of the plot here; it's between the plain brevity and quasi-universal quality of that story, and Fejos and cinematographer Gilbert Warrenton's dazzling, intoxicated infatuation with all the delightful ways they can tell it, that the film creates its own sparks, the ones that make us fall as head over heels for it as Jim and Mary are for each other. There's not nearly the space here to enumerate all the nonstop ways that that Fejos and Warrenton find to make Lonesome soar at every turn, sustaining the tone as the film's almost musical structure rises and falls, going all fortissimo here, slowing there for a more hushed, intimate, tender moment. But for one salient feature, there's the aforementioned Coney Island, which appears in an unforgettably lovely transition as dusk falls on the beach, where Jim and Mary have been hanging out in their swimming attire, playing in the water and getting to know each other, making pathetic attempts to impress (Jim claims he's a millionaire and clumsily, charmingly does a little flexing pose in an attempt to woo this fetching girl he likes, while Mary, for her part, plays the society girl). The perpetual motion of the camera in black and white on the crowded beach as the two flirt and tell their tall tales gives way to a dusk where everything fades, and suddenly we're in glorious tinted color and sound as the entirely artificial, swoon-worthy lights of "Coney Island" come up behind our fetching pair. Now, the words "it felt like they were the only two people in the world" are too clichéd to have much effect, but what Fejos and Warrenton do here to show us that feeling is one of the most delicately pretty, stunning, original things I've ever seen onscreen. We can hear Jim and Mary's voices now, and it's as if they can really hear and talk to each other for the first time, too. It's the perfect moment for them to haltingly confess, in a blue-tinted/moonlit, close-in two-shot, their true, working-class selves to one another, in an exchange/confession so humble, plaintive, and sweet, you may find yourself brushing away a tear; not since John C. Reilly and Melora Walters in Magnolia have I seen as convincing and heart-melting a depiction of the anxiety of wanting to be better than you are for someone you're falling for and want to fall for you.

With the prosaic truth about themselves having been revealed and the couple smiling and at ease in their relieved, now truly close togetherness, it's off to the amusements, where Fejos and Warrenton's camera takes us on a thrill ride -- one that doesn't stop until the film's conclusion -- to match the innocuously pleasurable activities Jim and Mary enjoy together, all of which seem to reflect or analogize their joy: the rotating-cylinder ride in which they literally fall for each other; the washing-machine ride, enhanced with more splashes of color, that spins to dizzy and agitate its passengers; the photo booth where their portraits turn out so hilariously bad that they (and we) have to laugh; the tossing game where Jim wins Mary a doll. Finally, there's the rollercoaster, on which we fly heart-stoppingly along with the couple through subjective shots as they rise and plummet, but where a malfunction leads to fleeting jeopardy for Mary and, worse, forces them apart in the ensuing confusion, followed by a frantic search for one another in the teeming crowd as a rainstorm begins to pour, with the growing fear (which we wholeheartedly share) that, without having exchanged last names or addresses, they'll be unable to find each other again.

There's one particular moment interposed within all of Jim and Mary's exuberant, madcap Coney Island galavanting, after the screen blushes to a pink tint and displays a band striking up the film's love theme -- Irving Berlin's "Always," as sung by "crooning troubadour" Nick Lucas -- where the picture itself, through an extraordinarily deployed split screen/montage process in which two halves of the screen rotate back and forth against each other in rhythm, seems to do a little two-step of its own in time with the music. That odd, extravagant, yet completely appropriate coming-alive and participation of the very contours of the frame in order to convey and celebrate Jim and Mary's reprieve from loneliness is as indicative a sample as any from Lonesome's overflowing, astoundingly creative cornucopia, exemplifying the film's free-spirited but accomplished, adroitly patterned way of turning an unelaborate tale of love trumping post-industrialized, big-city loneliness into something that blossoms onto the screen with all the vivid, layered grace and beauty of a flower. The film closes on the same song, played sadly on a phonograph to beckon the lovers back to one another and ecstatically reunite them, and you won't soon be able to get that tune's "I'll be loving yooouuu, alwaaaayyys" declaration of love out of your head; like any one of Lonesome's diverse but unflaggingly gorgeous succession of pitch-perfect notes, it will stay with you for a very, very long time.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

Using a print donated by the Cinémathèque français and working with preservation partner George Eastman House (among others), Criterion has given us incredibly well-restored picture quality in an AVC/MPEG4, 1080p transfer presenting the film at its original aspect ratio of 1.19:1. There are definitely signs of the film's age and the fact that it's been salvaged (however well) from an old print rather than created from a new one -- assorted visual flaws that are intermittently fairly noticeable, particularly in the last moments of the final reel. But by then the film, which overall has rather little in the way of the fading, scratches, and other visible signs of wear one actually expects much more of in films of this vintage (many of which have survived in much worse, irreparable shape or tragically been lost completely), has you so immersed in the experience allowed by the overall consistently high quality, it doesn't really register, and certainly doesn't take you out of the movie in a way meaningful enough for rebuke.

Sound:The film's monaural sound has been very nicely preserved on the disc's uncompressed PCM 1.0 soundtrack. This is not, of course, room-filling surround sound, but anything that could be considered a sonic imperfection (a certain tinniness to the music and sound effects, but actually not much with the dialogue, which sounds as clear and full as that in most films from the '30s or '40s on DVD) os decidedly due to the sound technology available in 1928 rather than anything overlooked in the mastering of the sound for Blu-ray, and everything sounds just as it should, with no sonic glitches to mar the experience.

--A full-length audio commentary by film historian Richard Koszarski, who rhapsodizes (and rightly so) over the film's astonishing accomplishments as he clues us in to what lies behind all the technical innovation on display. Koszarski also articulately draws upon his extensive knowledge to place the film in various informative contexts, including the silent cinema in general as it made its transition into the sound era, Fejos's very diverse body of work, and the once vulgar and commonplace but soon to be major Universal Studios' struggle at the time to establish and elevate its artistic credibility.

--Similar to what they did for their release of Kubrick's The Killing (which also included the earlier Killer's Kiss), Criterion has loaded their already-crucial release of Lonesome with two additional full-length features from Fejos that, while they have not undergone the all-out cleanup that has been done for the principal title, are a huge deal and make this disc a must own, as all the films combined represent an unusually expansive (re)introduction to a major, less-heard-of film artist. From 1927, the year prior to Lonesome, is The Last Performance, presented here in a truncated version, a Danish print (with the intertitles subtitled, of course) that leaves out the talking portions of the film. Still, it's remarkable and holds together very well (I honestly couldn't guess where the talking sequences would have gone in those versions). The story of Erik the Great (Conrad Veidt, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari) -- a middle-aged, internationally popular stage magician who, after a long courtship, gets engaged to his much younger assistant and then has to struggle with his own murderous jealousy when she falls in love with a handsome young man he's taken under his wing -- the film is many times more melodramatic and overstuffed, plot-wise, than Lonesome. But when you see Fejos's expressionistic touches and the inventive montage in full swing (for just a couple salient examples of visuals that just floor you, there are the crane shots crosscutting between Erik and an audience member he's hypnotizing with his eyes, and the magician's giant shadow spotlighting the assistant and her paramour when he first sees them together), and top that off with the all-around quite wonderful work from the actors, the plot's too-many busy convolutions scarcely matter.

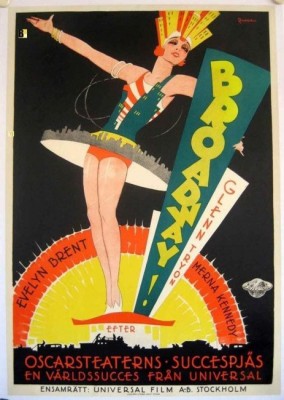

As for the other bonus Fejos film, 1929's Broadway, it has both the most conventional, even threadbare plot of the bunch -- something about a love triangle between a struggling, low-rent nightclub dancer (Lonesome's male lead, Glenn Tryon), his dancing-girl partner, their dreams, and the threat posed by a rich mobster who's after the girl -- but that droopy clothesline fades as we see what Fejos and his team have hung on it: swooping, luxuriant crane shots that give us panoramic views (in one impressive case, literally 360 degrees, which I still can't figure out how they did) of the impossibly cavernous nightclub and the little production numbers that go on there. The film is part gangster drama, part romance, part musical, but all spectacle; it's overall the weakest inclusion here, but that doesn't mean you'd ever want to deny yourself its considerable pleasures. (An additional extra for Broadway is a brief excerpt from a 1973 interview with the film's cinematographer, Hal Mohr (The Wild One), accompanied onscreen by scenes and archival stills illustrating his recollections.)

--To enhance our familiarity with the very impressive, thoughtful man who was the artistic mastermind behind Lonesome, Criterion has also included a 20-minute film essay on the life and work of Paul Fejos, evidently made in the mid-'60s (shortly after Fejos's death). Created in collaboration with Fejos's widow, it combines stills and film from the places, travels, and creative works most salient to Fejos's Renaissance-Man existence (born in Hungary, he lived all over the world, eventually becoming a well-respected anthropologist who made ethnographic films) with an audio autobiography Fejos recorded in 1963 as part of a Columbia University oral history research project.

--A 34-page booklet featuring an essay on the film by Phillip Lopate, a recap of Paul Fejos's career by Graham Petrie, and some notes on the film's preservation by George Eastman House Head of Preservation Dan Wagner.

Lonesome is a sheer delight. Straddling the gap between the silent and sound eras, it blends the inimitable visual ingenuity and freewheeling creativity of silent cinema at its grand artistic peak with the novel delight of hearing the characters speak, resulting in a hybrid that's one of the greatest, most touching and invigorating cinematic love stories ever told, in either silent pictures or sound. Mary and Jim (Glenn Tryon and Barbara Kent), whose voices we actually get to hear in a couple of scenes, are a struggling bachelor and single girl who've been left isolated and privately, restlessly dejected by their clock-punching, frantically hard-working routines amid the disconnected impersonality of a bustling urban milieu. But, unbeknownst to them, they're coming into a happier moment, entering a secret passage leading out of the lonely anonymity of city life; they're embarking, with some trepidation (it's likely, after all, that they'll end up feeling just as alone when they return as they did when they left their apartments), upon a paradisiac holiday weekend of rare leisure during which their unexpected, instantaneous meeting, connection, and love will at long last rescue them from their lonesomeness. The film is nominally set in Manhattan and on Coney Island, but it's a Hollywood-produced-and-shot feast of movie artifice that makes the surroundings and actions, through an tirelessly inventive filming style and exquisite set and production design, something much more resonant for being figurative, sometimes near-abstract. It's the ideas of The City, of Loneliness, of Pleasure, of Falling in Love, all coming to vivid life, rendered in a way that employs all manner of carefully selected color and movement and superimpositions, fades back and forth between the film's reality and its dreamscapes, and folds in some beautiful music (of the sort people make and the sort that the right two people can make together) to become something far above and beyond anything merely realistic.

The film's one-day/one-evening time span passes in an ebb and flow of clever, charming, gloriously expressionistic moments -- Jim and Mary's workdays, sunbathing on the beach, a carnival, a heart-stopping accidental parting and then an emotionally overwhelming reunification -- that are, under maestro Fejos's supple, inspired baton, a symphony, a ballet for two imparting, as faithfully and strongly as any movie ever could, the forlornness and rapture our lovers are experiencing. With sequence after delightful, fluid, adventurous, visually unpredictable sequence all building together into a rich, tender, multilayered harmony through brilliantly footloose montage; the absolutely lovely performances of Kent and Tryon; and plainspoken dialogue that sounds, in this context, like the very poetry of longing and love itself, Lonesome is a conceptually playful, aesthetically vital, unabashedly romantic, eye-popping rush of celluloid joy that nobody should deny themselves. On its own, it would be at the very top tier of "highly recommended," but combined on one disc as it is with two other (very slightly lesser) features by its amazing, too-little-known creator, it constitutes an indispensable building block for any movie-lovers' collection. DVD Talk Collector Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||