| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

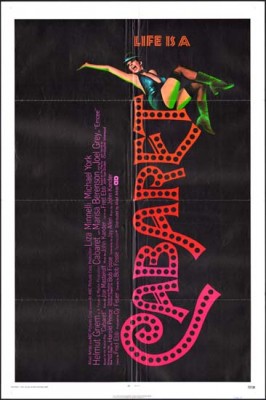

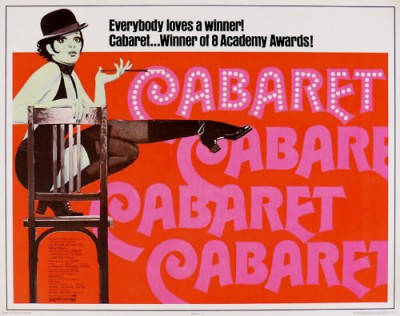

Cabaret

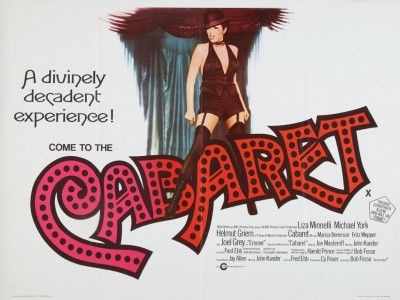

Like any bit of iconography, the image -- a woman dressed in quasi-fetish fishnets and black bodice, adorned with heavy makeup and sporting a bowler hat as she prepares to spring into action and strut her stuff on the stage -- often seems taken out of context; it suggests something brassy and strutting, selling much too short the multifaceted, turbulent, exceptionally dark stuff of which Cabaret, the 1972 Bob Fosse film from which this fascinating, suggestive figure is taken, is made. But its appearances have never before been misleading to quite this extent: Those responsible for the packaging design of the new Blu-ray version of Cabaret are apparently bound and determined to evoke the neutered, Fosse-lite likes of Chicago, airbrushing that famous female singer-dancer figure to the point of cartoonishness and transforming the bold, half-garish, florid swoop of the classic poster for a new, slick and sparkly look that truly couldn't have less to do with the film's themes, look, sound, or style. For, as anyone knows who's seen it and fallen in love with its heavy, heady, very ambivalent and ultimately shattering tone and textures, there's nothing glibly sleek 'n chic about Cabaret, despite its abundance of supple cinematic stylishness. Fosse was no stranger to the whipping up of a fantasyland of color, song, and dance for the silver screen; he had passed his own long moment in the celluloid sun as a dancer in more traditional kinds of movie musicals (the sort that reached its glorious apogee in Singin' in the Rain), and was already a well-known choreographer and stage director at the time he made Cabaret. But this was the early '70s, and the notorious Vietnam/Nixon malaise was setting in; people weren't really in the mood for cheerfully fake, idealistic stories with a champagne fizz, and Fosse's more conventionally genre-fied first musical feature, 1969's Sweet Charity, had been buried under the long-overdue death rattle of a once-booming and inspired genre that, in the '60s, had reached a bloated, financially unsustainable, artistically leaden, and socially irrelevant Oliver!/Sound of Music phase. Cabaret is, explicitly, an antidote to all of that, cutting like a knife through the stagnation of the movie-musical form and striking all the way to the heart of an irresoluble impasse -- the place where fragile, idealistic beauty, glamor, art, love, and freedom, the dazzlingly aestheticized world posited by many a Technicolor musical, meets the real world and finds itself clumsy, stumbling, inadequate, with not much to say about abundant and systematic oppression, privation, and brutality.

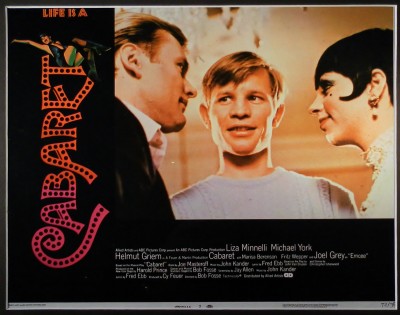

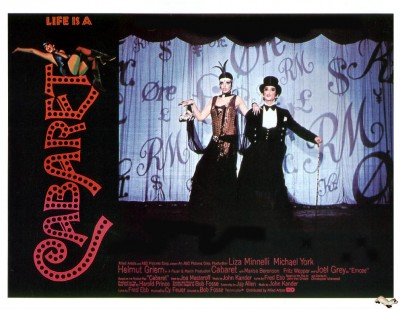

The star-crossed, adventurous pair at the center of Cabaret's engaged, insightful reckoning is comprised of an expatriate Brit, Brian Roberts (Michael York), and the self-consciously nonchalant/shocking American Sally Bowles (Liza Minnelli; two minutes with her here makes you forget the ever-tackier/schmaltzier ensuing years), with whom he accidentally finds himself boarding and bonding after he moves to Berlin in 1931 in search of...well, the kind of freedom that this determinedly effervescent Sally seems to live and breathe, and which was evidently not to be found back at Cambridge. Onstage at the Kit Kat Klub, the cabaret of the title, Sally and her fellow hoofers embody Weimar Germany's world-weary but restless need to push boundaries, explore, test every limit; the outrageously suggestive and rude dance numbers they very ably but almost sarcastically, confrontationally lurch through suggest that this might be a dead end. The most memorable songs performed by Minnelli are little masterpieces of talk-sung (and then, surprisingly, simmering to a boil) bleary realization, the sad hangover from all the champagne and money and flirting and social climbing and sleeping around that is her life as she tries to break into the movies when she's not on stage. The words and the way they're sung speak of a devastating doubt and longing for some impossible state of love, freedom, and beauty, an existential ache that can perhaps be masked by flash and fun, but will never really go away. Meanwhile, the club's (and the movie's) master of ceremonies (Joel Grey, not coincidentally tapped many years later by Lars von Trier for a small but crucial role in his anti-musical, Dancer in the Dark) -- a fiendish, petite, exaggeratedly randy ball of energy, whose tight, narrow features and cruelly oracular lips are rendered garish by pancake foundation and shrieking-red lipstick -- dispenses gnomic worldly-wisdom and gleeful observations about life, love, and society that range from sour to bitter (all through song; again, this is not your father's musical). His is the first and last face we see, suddenly popping into frame (close enough that we can see him through the fragmenting, obscuring scrim of glass through which we first barely, vaguely glimpse the film's world) to welcome, or at least gleefully beckon, us into this particular refraction of human experience, where illusion and reality coexist very uneasily and the other shoe is always just about to drop, hard, into the pressurized vacuum of artifice.

The "musical" part of the film is confined, in stark contrast to longstanding convention, almost exclusively to where song and dance would realistically occur; Grey's and Minnelli's shenanigans at the Kit Kat Klub become regular, punctuating interludes that quickly establish themselves as the meta-space of Cabaret, the Greek chorus that reiterates and comments upon the action. The stage is not Brian's world, so he never sings or dances, but there's always a sardonic, hysterically energetic, foreboding musical number coming up to reflect in some unexpected way (usually as disturbing as it is a pure cinematic rush of Fosse's perfect instinct for lighting, costume, and general mise-en-scène, and his neo-Busby Berkeley choreographing of dancers and camera in tandem) upon most of the action that he and Sally take part in outside the club. This includes the beleaguered love that develops between Brian's pupil of English (Fritz Wepper), a self-hating Jew who's passed himself off as Protestant, and a wealthy girl (Marisa Berenson, Barry Lyndon) whose family does not disguise their Judaism and are thus more and more boldly persecuted by the Nazis. There's also the burgeoning affair, in this free-love experimental atmosphere, between the heretofore mainly gay Brian and Sally, whose vulnerability and steadfast friendship has proved irresistible to him -- which then in turn segues to an even more experimental, dizzying, bisexual three-way affair between the friendly, poor, starving-artist couple and a handsome, free-spending, filthy-rich baron (The Damned's Helmut Griem) whom Sally has her eye on and who seduces both showgirl and Englishman into a whirlwind romance.

Around it all, there's the creeping rise of Nazism that Brian, Sally, and the baron are too involved in their explorations, adventures, and frivolous, casual (and easily broken) plans to give much attention to until it's much too late to object in any meaningful way. It's this last aspect that gets uglier and more brutal until it overtakes and interferes, casting a long shadow over the film's individual dramas and stories of people who, whether through wealth, pluck, or mere hope, wanted to escape into a utopia without facing, vanquishing, or even noticing the ferocious, vicious opposition steadily gathering terrible force all around them. The film's central scene, the most penetrating glimpse into its heartbroken skepticism about performance and entertainment, may come with the one moment that a "number" occurs offstage, when Brian and the baron finally flee a pastoral inn after a Hitler Youth has begun singing a nationalistic/right-wing anthem, plaintively and sweetly, progressively joined by more and more average-German fellow diners until the pretty song becomes a screed, a juggernaut of dangerously emotional, violently jingoistic pride -- a beautifully rendered, sincere and heartfelt, impassioned artistic/musical expression mutating into vile propaganda, revealing art and beauty as morally neutral entities that can just as easily serve despicability as anything noble or innocent. Against this encroaching backdrop of who knows what murderousness, the perpetual instability and foreboding of Berlin starts to wear on them, bright hopes and ideals slowly but surely tarnish, and Brian's and Sally's plans together, in the face of some cruel, unavoidable realities of biology, attachment, and sexual orientation that can't be ignored no matter how troublesome they are, fade and buckle into an anti-climax. On warm and friendly terms, Brian leaves Berlin; Sally, heartbroken but resigned, stays to pursue her nonexistent acting career; and, as the film's petrifying final pan and freeze-frame emblazon indelibly upon our consciousness, it will be the fervent, rigidly potent, hate-filled Nazis, not the shamblingly squalorous, hopeful, adventurous dreamers or the devil-may-care singers and dancers, who will inherit the power and the culture in what was once a haven for those seeking brave, risky political, social, romantic, artistic, and sexual freedom.

There's a free-associative feel to much of the intercutting between the musical moments and the characters' "reality," sometimes recalling Nicolas Roeg's hallucinatory editing strategies in his own '70s work (Walkabout, Don't Look Now), while Fosse's overall visual sense, created under the auspices of cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth's (2001) rich, often availably-sourced lighting (for a look that's often dark and cloistered, but with a fine, immediately present sense of detail and gesture, with a naturalistic starkness to what illumination does appear, and the somber or darkened spaces creating an open field for rich plays of light and shadow, especially noticeable in the musical performances), has that woozy, relaxed, free-roaming, unpredictable quality to it familiar from this particular cinematic era, which, combined with Fosse's playing markedly fast and loose with the dimensions, rhythms, and structures of his storytelling, aligns Cabaret in some important ways with much of the other timelessly innovative popular artistic enterprises of the era. These and the many other overlaps with '70s cinema create an intriguing trail: Lindsay Anderson's O Lucky Man! worked with musical performances that played a similarly commentating role; and even Sally Bowles's musical temperament, longing for future shock, and (not least) famous bowler hat uncannily suggests an= mirror image of Kubrick's Clockwork Orange antihero of the same year. More generally, Cabaret, like roughly contemporaneous New Hollywood standard-bearers such as Bonnie and Clyde and Thieves Like Us, is a restless, skeptical, stock-taking film, harking back to a moment of turmoil and instability, some anomalous historical window of short-lived liberation and quasi-martyred defeat. Its timely juxtaposition of romanticized nostalgia and razor-sharp sophistication extended beyond cinema during those uncertain years; it also surfaces strongly in the great glam rock of the era, particularly that of Roxy Music, which often had nearly as much of a Weimar/cabaret/Brecht-Weill obsession as Cabaret does (it's little wonder that Toni Collette's character in Velvet Goldmine bears such a very strong resemblance to Sally Bowles).

The finale finds Sally right back where she began, and we sense that's likely where she'll stay, on amicable but uncertain, insecure terms with the world, if she and her idealism can even survive the chokehold of the Nazis and the consequent war. We leave her on the stage, where Fosse and screenwriter Jay Presson Allen (Marnie), working from various, eccentrically but brilliantly combined sources (including Christopher Isherwood's Goodbye to Berlin and several previous dramatic and musical adaptations), have saved the best for last: Sally belts, then croons, then belts even harder the famous title song, with its undercurrent of mortality, taking us out on a half-fatalistic, half-optimistic note in a splendiferous orgy of stage-lighting color as she raises the roof with her "Start by admitting/From cradle to tomb/It isn't that long a stay...life is a cabaret!" Because of everything that's come before -- because Sally is still reeling from dreams worn out or betrayed or exposed as foolish, because the whole world as anyone knew it is more or less about to end in a way ever so much bigger and more horrific than her and her song -- this is irony, bittersweetness at its most exquisitely affecting. "Life is a cabaret," she so unequivocally insists with her voice and gestures, and yet...it can't be, as we know, as Brian has learned, and as Sally surely realizes by now. It's an excruciatingly elusive dream, an impossibility that the rending coda, with its sustained freeze-frame glimpse of an audience packed with swastikas, makes the film's last word as the credits come up. Regardless of whether you've often been moved by a movie musical or you tend to regard the genre with suspicion, this movie musical is self-aware and committed enough, in a way that will always feel shockingly, shatteringly modern, to touch you in a way that no film of its kind had really attempted before, and that precious few have ever been smart, resourceful, or passionate enough to try since.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

The AVC/MPEG-4, 1080/24p transfer, presenting the film at the widescreen aspect ratio of 1.78:1 (apparently a slight modification from its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1, though a quick comparison seems to indicate we're getting more of the image, not less, in this slightly less matted AR), is almost perfect; the colors and contrasts of the film are fantastically true, vibrant, and well-preserved; shadows and light and skin tone all look ; darks are nice and solid; and only on several brief occasions is there even a question of overzealous digital noise reduction; otherwise, the texture and grain make for a wonderfully cinematic presentation. It's a minutely conscientious transfer all around, and well deserving of our full approbation.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack conveys the film's sound with a new sharpness, clarity, and layers of highs and lows, but never overdoes the modernization or sacrifices the nuances or intimate feel (especially when it comes to the dialogue) on the original 4-track stereo soundtrack. No distortions or imbalances mar the full immediacy of the spoken dialogue, the rumble of an elevated train passing overhead, or the brassy, drum-heavy, and often belted musical numbers.

Extras:New features exclusive to this new (2013) Blu-ray edition of Cabaret are:

--Feature audio commentary by Bob Fosse biographer Stephen Tropiano, who knows the film from inside and out and can tell you both in what ways the film's Kit-Kat Klub resembles a Weimar-era cabaret and about how authentic period clothes, in addition to pointing out salient details within the scenes and in the way they're structured, all in a tone that's conversational and, with Dr. Tropiano's softer-spoken manner, suggests the earnestness of a movie-pal confidante.

--"Cabaret: The Musical That Changed Musicals" (30 min.), is a reminiscence and tribute to Cabaret that extends further to encompass Bob Fosse's career trajectory (with the movies as his first love/ambition, though of course dance, choreography, and the theatre played the bigger role). Narrated by Neil Patrick Harris (whose own turn on the stage in Cabaret on Broadway, in the Joel Grey role, was a definitive post-Doogie turning point), and featuring Tropiano and fellow Fosse biographers Sam Wasson and Martin Gottfried, along with recent interviews with Minnelli, York, Fosse's daughter Nicole, multiple Fosse colleagues from throughout his film career, and admirers/collaborators ranging from Chicago director Rob Marshall to Bebe Neuwirth.

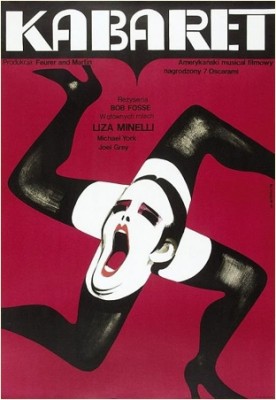

--The package's "digibook" presentation means a sturdily designed outer casing and a thick, glossy booklet-insert that, while I absolutely do not care for the slick 'n glitzy design update from the much more apt, richer, darker feel of the original posters and artwork (the lone aspect in which the DVD is actually better -- get a load of that Vegas-meretricious font they chose to replace the perfectly lovely and much more representative lettering style of yore!), does offer an impressive rundown of the film, including thumbnail-length but thoughtful cast and crew biographies and detailed notes on the film's production, reception, and place in film history.

Bonus features grandfathered in from the 1997 DVD edition include:

--"Cabaret: A Legend in the Making" (17 min.), with earlier interviews with Minnelli and York, as well as a handful of the film's original producers and overseers from ABC/Artist's Alliance Films not included in the more recent supplement.

--"Recreating an Era" (6 min.), an original featurette created to promote the film, narrated in movie-advertising language (a minus) and packed with behind-the-scenes footage and on-set interviews (a huge plus).

--"Kit Kat Klub Gallery," a bevy of very short clips, divided by speaker (including Minnelli, York, and Gregy, along with practically everyone else involved with the film, from screenwriter Jay Presson Allen to composer Fred Kander.

--The film's original theatrical trailer (not remastered, unfortunately, nor even widescreen; it looks and sounds more like it would have if viewed on TV in 1972).

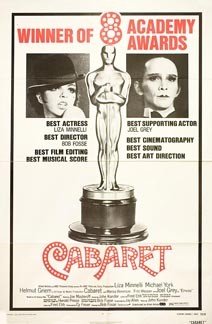

Legendary dancer/choreographer Bob Fosse's first successful film as a director, Cabaret earns its enduring popularity and acclaim as a musical that works against itself, with a relentless undertow of doubt about escapism and entertainment surging powerfully beneath its decadent, half-mad, yet brilliantly and vividly shot and performed musical numbers. Neither Michael York (as the timidly mostly-gay English translator Brian Roberts) nor Liza Minnelli (as the determinedly vivacious singer/dancer/actress Sally Bowles) ever topped their roles here, as expatriates, ambitious artists, and romantic/sexual explorers who mean to take full bohemian advantage of the new freedoms offered in unstable Weimar/Depression-era Berlin; for his part, Joel Grey, as the master of ceremonies for both Sally's employer, the Kit Kat Klub cabaret, and for the film as a whole, is as tarted up, withered, and slap-happy as the beleaguered, sick soul of Deutschland itself as it woozily slides into the Nazi era while nobody seems to notice, care, or realize the horror to come until it's too late. Fosse's visual and tonal expertise, imagination, energy, and skill as a director underscore the fact that the medium was his first love, while on the story/structuring front, he and screenwriter Jay Presson Allen cull several sources -- including Christopher Isherwood's Berlin stories and a couple of related stage plays/musicals -- to come up with the perfect balance/juxtaposition between the rich personal territory between the lost but open-hearted/minded leads, the drama of their lives and fragile hopes, and the turmoil in the world around them that makes their personal troubles amid hectic glamor feel more and more sadly beside the point. Fosse isn't regularly mentioned in the same New-Hollywood breath as Altman, Ashby, and Scorsese (and the particulars of his style have more in common with across-the-pond contemporaries like Nic Roeg, Lindsay Anderson, and Kubrick), but Cabaret is the perfect American-made musical revival for that era -- the '70s, burdened with Nixon and Vietnam and the failure of the '68 revolutions -- when such a fantastical genre was assumed to have lost all credibility or relevance, and the film's bracingly modern feel will likely outlast us all. Its looking at once backward (its finely-considered period detail troublingly elicits simultaneous nostalgia and real unease) and forward (only A Clockwork Orange had such audacious future-retro aesthetic brio) with weary but lovingly observant eyes holds up extremely well; it remains a ravishing feat of sound and vision that dazzles and enthralls with all the singing-dancing strength of a good old-fashioned musical, but is haunted every step of the way by (and haunts us in turn with) its open acknowledgment, woven right into the fiber of the film through the musical numbers and their running-commentary relationship to the story, that there's a social and political world to which we all belong that exists outside the cabaret, and if you're there to ignore or hide from its uglier or more frightening realities, you're liable to glance over one night and see them sitting at the table next to you, clapping and singing along. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||