| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Pierre Etaix: The Criterion Collection

Please Note: The images used here are taken from promotional materials, not the current Blu-ray edition under review.

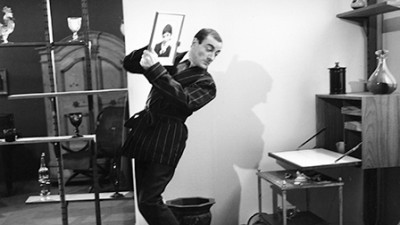

Well before and long after he became a filmmaker, Pierre Étaix's real forte and calling has always been as a clown -- a French clown, in particular -- and in a way, that tells you much of what you need to know about him and the charmingly off-center sensibility and aesthetic he brought to the five features and several shorts now brought together in Criterion's new Pierre Étaix box set. The idea of a subtle clown or of sublime slapstick would seem to be highly counterintuitive to us more straightforward, blunter Americans, to the point of all the overblown cultural divides between the U.S. and France, the humor-disconnect -- the oft-derided French embrace of Jerry Lewis's cinematic genius (Lewis has, tellingly, been a longtime friend and mutual admirer of Étaix) being the most common example -- may be the deepest and widest. But subtlety and sublimity, finesse and intricacy and surprise -- all in service of gags, pratfalls, and slapstick adding up to sometimes surprisingly moving and/or profound insights about life and human nature -- are what this clown Étaix aims for and almost always attains in this handful of films, all made between 1961 and 1971, that comprise his compact but thematically and aesthetically full-to-bursting filmography. Here, the seasoned clown takes off the makeup and frills to expand the trail blazed by his cinematic idols Chaplin and, especially, Keaton -- retaining the expert physicality and comic timing of clowning and integrating it into an apparently indistinct, beleaguered-everyman persona in front of the camera, and into a restless, seeking experimentation and innovation behind the camera, an auteur very deliberately and exquisitely shaping his onscreen world into a place where the ennui and loneliness and uncertainty (in addition to all the other minor frustrations, dissatisfactions, and malfunctions) of life become chain reactions leading to utterly unpredictable, supremely well-choreographed comic chaos.

Étaix and his constant collaborator, legendary screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière (who's had a hand in everything from The Tin Drum to Birth to The White Ribbon, but whose collaborations with Bunuel, the comic-absurd-strangely poignant Belle de Jour foremost among them, seems most germane here) started off on a small, manageable scale with two shorts, 1961's Rupture and 1962's Happy Anniversary (Joyeux anniversaire). In the former, which takes place almost entirely within a little office whose potentialities for mishap and disorder Étaix and Carrière thoroughly exhaust, a young man (Étaix) receives a break-up letter from his lovely paramour and attempts a reply, his fountain pen, inkwell, and very desk and chair conspiring to render this melancholy but exceedingly simple task positively Sisyphean. In the latter short, Étaix expands his scope considerably, incorporating gags about Paris's street life and daily routines into another simple task made comically difficult and interminable -- a young husband's (Étaix again) attempt to pick up some flowers on his way home from the office to an anniversary dinner his wife has prepared. The visual strategies -- the pacing, composition, and editing -- beautifully brought to bear on the running gags, as well as the inspired cross-cutting between the husband's prolonged journey home and the increasingly bored, thirsty, and hungry wife awaiting him let us actively witness Étaix's natural flair for the language of cinema growing by leaps and bounds.

The next step was for the filmmaking duo to take their now-proven skill at the finely-developed and beautifully executed sketch and carefully parlay it into their first feature, 1963's The Suitor (Le Soupirant), layering and nesting multiple bits that could have worked quite elegantly as individual short films into a loosely but stably connected whole. The film riffs on the dutiful quest for a spouse undertaken by a solidly bourgeois, if dream-prone, young man (Étaix), who sees perfect love all around him in his well-appointed Paris quartiers but can't seem to find it for himself, try as he might. He plays out fantasies of le grand amour in his bedroom in his parents' house; he gallantly picks up a young woman whose gauche, tipsy, but insistent clutches he must then try, via a forced "romantic" game of hide-and-seek drawn out splendidly for all of its cumulative comic payoffs, to flee. The film's most visually witty segments involve the young "suitor"'s seduction-by-television at the hands of chanteuse-starlet Stella (France Arnel), on whom he develops a stalkingly obsessive crush that's doomed to go the way of all crushes (the film lets him down easy, his disillusion comic rather than painful), as well as his amusingly fusty, prototypically bourgeois parents and household -- his mother's addled, haughty, polite veneer and his father's Rube Goldberg-device strategies for sneaking his vices of tobacco and liquor. Meanwhile, an ongoing gag about the language barrier between the family and their lovely young live-in Swedish housemaid (Karin Vesely) pulls the whole affair together in a sort of delicate bow, lending the film a connective emotional suspense and urgency; could the true love he seeks be sitting right under this young man's nose, and will he realize it in time?

Much more than a well-integrated series of variations on a theme, Étaix and Carrière's followup to The Suitor, 1965's Yo Yo, is a tremendous leap forward, probably the most ambitious and accomplished of all these very worthy efforts. Inspired by Fellini's 8-1/2, it's Étaix's nostalgic, conflicted, ambivalent but strong, passionate love letter to his two touchstones: the averbal grace and physicality of silent cinema à la Chaplin and Keaton, and the artistry of the circus. The film has an unusual, bipartite structure, like Full Metal Jacket or Storytelling, in which a long prelude gives way suddenly to the connected but different "main" film, with Étaix successively playing two principal roles: In the first part, set in 1925 and played out in well-studied but never slavish "silent" style, Étaix is the lord of a countryside chateau whose every whim is indulged with an absurd pomp and excess suited to the gin-and-flapper era (in one hilarious and magnificently shot scene, a simple walking of the dog is an elaborate ritual involving a slow-driven limousine with Étaix holding the dog's leash from within); the Depression (and the talkies) arrive and find him ruined financially but fortuitously reunited and out on the road with the pined-for love of his life, a circus equestrian, and their son, a little clown called Yo Yo. Flash forward to WWII: The grown-up Yo Yo (Étaix again) is a celebrity clown on the rise, whose ever-escalating fame and fortune will find him successful and profitable in the wittily-spoofed TV era, but who seems to be swept by time, progress, and success further and further away from his roots, the legacy of that now-crumbling family chateau and the modest but proud work ethic and spontaneous creativity of the traveling circus. The film is packed with lovely detail (e.g., the little yo-yo Étaix is playing with when we first encounter him as Yo Yo's father), and the work of his perennial technical crew -- cinematographer Pierre Levent (who'd shot everything up until then, with Jean Boffety taking over on the subsequent two features), editor Henri Lanoë, and composer Jean Paillaud, whose delicate, recurring melodic air becomes its own unforgettable character in Yo Yo -- is never finer. Étaix's inspired way with the medium is now superlative; the narrated transitions from era to era, for example, are perfect little comic thumbnails of history/sociology/popular culture, and the film's stream of wonderful gags merges and flows seamlessly with one circus family's story of forward momentum into the future and its genuinely touching, sad concurrent undertow of a sadly receding past. This film is the crown jewel of Étaix's career.

But Yo Yo was as much a commercial failure and critical mixed bag as it was, at least in retrospect, an unqualified artistic triumph, and Étaix's and Carrière's next effort, the omnibus film As Long As You've Got Your Health (Tant qu'on a la santé) is something of a retrenchment. The film is blatantly episodic, consisting of four unrelated shorts (though it initially ran in a different form with some attempt to tie it together, Étaix was very dissatisfied and later re-cut and altered the film to its present state). These are straight-up comic sketches -- an insomniac (Étaix) gets wrapped up in the vividly imagined horror novel he's reading; a moviegoer (Étaix) witnesses and/or suffers all the indignities that can befall one at the cinema (talkers, seat-stealers, with clever various POV shots of the way the big screen looks from the worst seats in the house); a city full of traffic-jammed motorists whose vehicle sport "smile, smile" bumper stickers goes slowly crazy to the incessant, slowly but consistently increasing volume of a jackhammer, with Étaix driven to visit a prescription-dispensing doctor who's crazier than any of them; and an Elmer Fudd-like hunter (Étaix once more) crosses paths with a picnicking middle-aged bourgeois couple and a crusty farmer trying to build a fence -- that work just fine independently, to the point that it seems rather unnecessary to have lumped them together arbitrarily into a feature. (As if to further make that case, a segment called Feeling Good (En Pleine forme), with Étaix as a traditional, DIY camper confronted with the rise of commercial campgrounds, was originally part of As Long As You've Got Your Health but was changed out for the bit about the hunter and the picnickers, and is included here as a stand-alone short.)

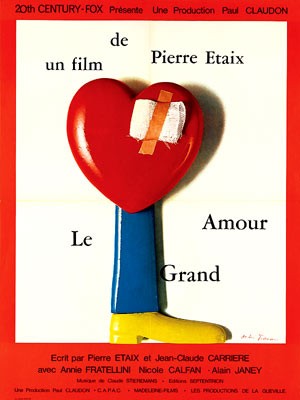

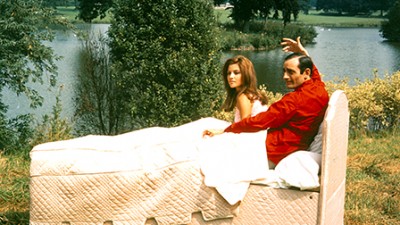

With 1969's Le Grand amour, however, Étaix and Carrière fashioned another full-fledged, deceptively simple-premised feature to nearly rival Yo Yo in accomplishment, if not quite in ambitiousness of conception. The subject here is the bourgeois-to-a-T marriage of Étaix's character to a young lady (Annie Fratellini, who became Étaix's wife in real life) whose father owns a manufacturing plant and has a plum grooming slot available to any future son-in-law. But the typical problems that beset marriage -- the subsidence of the honeymoon period, the clashes with the in-laws, the libido-sabotaging routine, infidelities suspected or actually contemplated/carried out, midlife crises, nosy neighbors/friends and their unsolicited meddling -- are played out in such flights of visual imagination, it has the paradoxical effect of raising the emotional stakes and sweeting the superficially bland, predictable bond between the couple. Just a few examples from the vast cinematic palette accessed by Étaix to vivify a familiar (but eternally interesting) story of how a marriage survives/how to survive a marriage: The spreading gossip of neighborhood busybodies is seen, depicted, rather than heard, exaggerations included, so that what we see at first as Étaix's innocuous glance at a beautiful woman in a park becomes, over several replays as the story has its ripple effect, his jumping directly behind a bush with her, clothes and accessories flying; when Étaix has an amorous dream about the fresh-faced and short-skirted replacement (Nicole Calfan) of his retiring secretary, his bed floats out of the flat and out into a land of fellow dreamers all cruising the French motorways in their own beds; and the unreliable selectiveness and fickleness of memory and emotion are highlighted when Étaix recalls and re-recalls the history of his love life, switching details back and forth, to the consternation of a waiter also present in the memory, who has to keep catching up to serve Étaix at a new location each time the recollector changes his mind again. It's a marvelously clever, affectionate film -- Étaix's second masterpiece, after Yo Yo -- that reveals unexpected insight and depth.

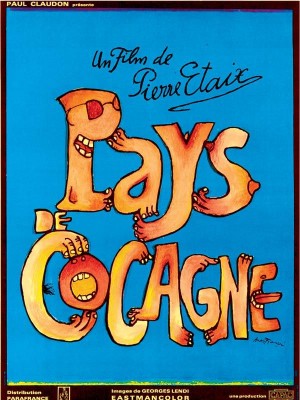

Le Grand amour was, unfortunately, to be his last narrative film work for many years, but not before he went out with an apocalyptic bang: 1971's Land of Milk and Honey, ostensibly a documentary Étaix was commissioned to make while traveling with Fratellini (a singer in addition to clown and actress) in a radio station-sponsored musical revue, is an incisive, relentless picture of a consumer-celebrity society in an orgiastically self-destructive mode. Starting with Étaix's interviews with the self-deluded, cynical, and/or barely coherent participating in the American Idol-like amateur stage included in his wife's traveling show, he takes his camera out into the provincial holiday hot spots he finds himself in, and what he sees isn't pretty: Tourists packed like sardines onto beaches and into campgrounds; shrill, omnipresent advertising; and mind-numbing waste, clamor, and confusion signified by nonstop humiliating amusements and cheap thrills -- eating contests, jingoistic parades, shrieking publicity tours by radio DJs, and the like -- participated in by what appears to be a uniformly desperate French populace. Despite a prelude in which Étaix does what he's known for in a delightful introduction in which he illustrates the problem of cutting his copious footage into a coherent feature by having what looks like miles of celluloid physically multiplying, overwhelming, and chasing down him and his editing-table collaborators, what follows is so acutely politicized and angry -- and very effectively so, I might add, for all the incongruity of its coming from the unflappable, lighthearted Étaix -- it could've been made by the Godard of the same period, which is to say after the questions raised by the student/worker/intellectual near-revolution May 1968 were presumed to have been silenced in favor of blissful ignorance, a retreat embodied here by the mumbling or baldly reactionary responses Étaix gets to his questions about the intermingling of celebrity, technology, advertising, and sex saturating the culture, all summed up nicely in a single camera movement away from a big black newspaper headline proclaiming economic crisis and austerity, out toward a crowd of unsmiling vacationers slurping ice creams. Land of Milk and Honey is a fascinating and urgent document made to be unsettling and alarming by someone who clearly was himself unsettled and alarmed; its outrage over the crudity, ugliness, and waste of an unfettered consumer society is nothing if not valid and prescient. But "funny," it's not; the only way in which this savage satire resembles most of Étaix's other pictures is in his putting conscience and principles -- his vision, whatever that might be -- before his popularity and public success. It was to be his last chance for a very long time: This unmistakable statement of anxiety over, and not a little disgust with, celebrity/consumer culture effectively removed Étaix from that maelstrom (the society of the spectacle in which he'd taken pains in the film to include himself, too), and the most fruitful and audacious chapter of his career as an auteur had come to an end.

It wasn't until 2010, after decades of legal holdups involving the distribution rights to these treasurable films, that the restoration and revival efforts were begun that have now culminated in the previously unimaginable opportunity to have Étaix's body of work at our fingertips, all looking/sounding better than it ever has since the first projections of the first spanking-new prints. Étaix's work is vital to the home-video library of any fan of Jacques Tati or Chaplin or Keaton, of course -- anyone who appreciates the kinetic, poetic, dance-like quality that can be reached through filmed physical/slapstick comedy -- but it's not just the re-experiencing of their joyful, eccentric, handcrafted pleasures that will entice you back, though that alone would be sufficient. It's also that they're such densely and intricately layered experiences that one feels certain of catching something new, some previously overlooked little moment or gesture or yet another payoff to a gag, on the fifth or sixth or tenth viewing. The rewards of Pierre Étaix's films are so many, ranging from immediate to long-lived, from the instantly, ticklingly appreciable to the lingeringly subtle; it would never have been too soon to start availing ourselves of them, but if such a long wait was necessary to getting them all at once and as gloriously well-presented as they are here, it was well, well worth it.

Video:

An announcement that appears before each of the entries in Pierre Étaix informs us of the massive restoration that was undertaken in 2010 of the films' badly worn and poorly stored materials, boasting that the color and texture of their image has been successfully restored. This claim is fully supported by the transfers here, each of which presents the film at its correct original aspect ratio (1.33:1 for the first two shorts, 1.66:1 for the remainder of the films) and looks just wonderful, the very nicely restored black-and-white contrast of Yo Yo standing out in particular, but with the colors in Le Grand amour glowing warmly and vividly, too, with no fading or dirt/debris of any serious note in any of the films, and with a lovely celluloid texture that retains the cinematic "grain" of the films without over-smoothing/flattening with digital noise reduction (DNR). A very, very fine job that does full justice to the films' visual qualities.

Sound:Each of the films' original mono soundtracks has been very well-preserved as an uncompressed PCM 1.0 track (in French with optional English subtitles), in an accomplishment equal to the careful restoration work that's been done for the images. The texture and tone of the original sound remains (this isn't room-filling stuff, but everything is quite clear, crisp, and as full as possible for the technology of the time and Étaix's particular, post-synching methods for gaining just the right exaggerated sound effects), with no distortion or imbalance and literally none of the audio flaws of aged/worn film prints such as hissing, popping, or clicking.

--Pierre Étaix, un destin animé (approx. one hour), a 2011 documentary by Étaix's wife, Odile, featuring in-depth and thoughtful interviews with the filmmaker/clown, his constant collaborator and longtime friend Jean-Claude Carrière, his son Marc, actor Roger Tripp, and others, all of whom delve into some significant, interesting, and revealing detail about Étaix's biography and his experiences, approaches, and aspirations as an artist/entertainer.

--A new video introduction by Pierre Étaix to each of the films (approx. four to five minutes each), with the filmmaker summing up his thoughts and recollections in a succinct way, often with surprising candor regarding the budgetary and personality difficulties and frustrations often involved in getting his films made, distributed, or appreciated.

--A beautifully designed cardboard-sleeve package including a thick booklet on high-quality stock, loaded with eye-pleasing stills, posters, and graphics and an essay by critic David Cairns that surveys Étaix's filmmaking career.

One more reason to thank the cinema gods (or at least Criterion) for the second life afforded to lost, orphaned, or neglected films by Blu-ray/DVD, Pierre Étaix represents the full, grand revival of the once and future French clown's incredibly rich and unique decade-long foray into filmmaking, the box set collecting an entire filmography (five features and three shorts) that have been lost to the public for years due to legal snarls. Étaix was a protégé of the great French comic cinéaste Jacques Tati (Mon Oncle, on which Étaix collaborated heavily with Tati), and he works in a similar, though quite distinct, vein, taking his "ordinary," self-effacing, put-upon-everyman physical-comedy persona through gags that are so elaborate and thoroughly exploited that they develop a kind of subtlety; it's slapstick spun out and savored into something sublime. Like his forebears Chaplin and Keaton, Étaix takes extremely simple premises drawn from the harsh frustrations, oppressions, and more melancholy facts of life -- the evasiveness of True Love in The Suitor; the merciless trampling of modernizing technology and corporatism over true, impractical, joyous art in Yo Yo; the inevitable ups, downs, and itches of marriage in Le Grand amour -- and lightens those crushing burdens, playing them out in cartoon physicality, acknowledging and deftly, hilariously exaggerating their absurdities.

As a filmmaker, Étaix's poker-faced but unflinching irreverence, inventiveness, and adventurousness with the camera and the soundtrack render him a contemporary of the Fellini of 8-1/2 or the Bunuel of Belle de Jour (Bunuel's longtime co-writer, Jean-Claude Carrière, is Étaix's collaborator on most of these films), his body of work capped off on a shockingly confrontational, Godardian note by a documentary-turned-satire -- The Land of Milk and Honey -- so scathingly critical of what French society had become that it rivals Weekend. Also packed in here, among and within the major works, are Étaix's delightful shorts and sketches, all bringing us into a world in which the simple, earnest, average man summed up by Étaix is thwarted at every turn by everything -- fountain pens, cars, pill bottles, coffee presses, etc., etc. -- but marches bravely onward with a propriety blend of good humor, obliviousness, and shrugging resignation, qualities that are both constants of Étaix's unassuming yet indelible screen persona and masterfully evoked visually and aurally throughout the films via his skill and effort as a director. It's a treasure trove of comedy as visually/physically creative and precise as it is (save for The Land of Milk and Honey) relaxed, easygoing, "light": Pierre Étaix represents the resurrection of a major filmmaker for an audience that has until now been unfairly deprived of his particular, wonderful flavor, and it's a very safe bet to be the cinematic rediscovery of the year. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||