| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Book of Life / The Girl from Monday, The

Where do you go after Henry Fool? Hal Hartley's 1997 film -- his magnum opus, by far his costliest effort to that point, and his next-to-last film shot on actual celluloid (he left 35 mm behind for good, it seems, with 2002's anomalous, financially disastrous No Such Thing) -- is bound to stand the test of time as one of the best, most unique avatars of that decade's U.S. independent-film boom, but in one significant way, it was also very much (and very fortuitously) of its moment, marking the tail end of an era: Even then, the willingness of financiers and distributors to take risks on an auteur's eccentric personal vision was beginning to narrow after it became clear that few such cinematic voices would deliver something as popular and profitable as Pulp Fiction, and it seems exceedingly unlikely, for those reasons among others, that something as audacious, odd, and individualistic as Henry Fool could get made or distributed now in anything like the way it was then. Hartley, always informed and sophisticated if nothing else, was abreast of the situation, however, and the direction he took next seems in retrospect not just ingenious but prescient: In order to keep his vision and aesthetic not just uncompromised but continually fresh and evolving, he stopped looking to "get" films made, latching onto the financial and logistical freedom to just go ahead and make his movies promised by the then-embryonic, rough new technology of digital video, and the latest entry in Olive Films' ongoing rollout of home-video re-releases of Hartley's work is a double bill charting the director's first forays into that strange, exciting new domain of filmmaking. Hartley talked the French television producers who were commissioning his next project, 1998's The Book of Life, for a millennium-themed series of programs, into letting him use DV as a way of turning the minuscule budget they were offering into a full-fledged movie; in 2004, Hartley took the next step, shooting his next theatrical feature, The Girl from Monday, using the cheap, flexible, portable technology.

What's remarkable about these two films, and what makes them of an aesthetic piece and so suitable for pairing on a single disc (above and beyond their wry, sardonic, deeply felt, and melancholy concerns with the possible futures, or lack thereof, of the human race) is their witty celebration of the particular look of digital video, very noticeably un-film-like at the time, and wonderful, fresh integration and enmeshment of those visual properties into the feel and meanings of the stories Hartley's telling. They are, at least, despite any flaws they may have, brilliant examples of form and function as complementary-verging-on-inseparable, harmonizations of technological, aesthetic, and narrative aspects that flow together and blend into dynamic yet whole works of art that become more than just the sum of their parts.

When I eagerly attended The Book of Life (which, as mentioned, was made for French TV and did not receive an official theatrical distribution) at a festival screening in 1999, I went as an enthusiastic fan/booster of Henry Fool and an even more avid aficionado of the great English rock singer/songwriter Polly Jean Harvey, whom Hartley had intriguingly cast as the film's female lead (playing a circa-1999 Mary Magdalene, no less). I was disappointed; Harvey's character is rendered as tough-contemporary-chick, not timeless/majestic rock goddess (I'm afraid I was hoping she'd be playing herself, which wouldn't have been fun or interesting for filmmaker or actor), and worse, the film seemed to me a slick, overly hyper, glib piece of work unworthy of Hartley or Harvey. Having now revisited and reconsidered it, I'm happy to report that, as has too often has been the humbling case, my younger self was unfair and wrong. The film -- which tells the story of how, as New Year's Eve 1999 approaches, Jesus Christ (Martin Donovan, part of Hartley's troupe of regulars since 1990's Trust) returns to earth (New York, to be exact), his personal assistant "Magdalena" (Harvey) in tow, to bring on the apocalypse at the turn of the millennium, as an understandably irritable Prince of Darkness (Thomas Jay Ryan, reprising his devilish title role from Henry Fool) lurks in Manhattan's watering holes and continues to plot and scheme right up to the wire, mingling with hapless, weak, or self-destructive New Yorkers (potential mismatched couple Dave Simonds and Miho Nikaido as especial targets) in hopes of tempting and damning a few last souls before time's up -- is a droll, aesthetically adventurous, only somewhat irreverent retelling of the end of days, with a ton of smart, funny, rapid-fire, screwball-derived, classic-Hartley dialogue exchanges and a surprise, very moving happy ending that defuses the dread to float in more contemplative and wondrous waters.

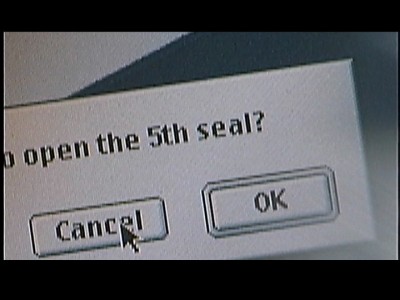

The tall, authoritative, serious-faced Donovan is a suitably earnest, torn Prince of Peace, naturally reluctant to bring the world to an end by clicking open the seven-seals files he's got on the top-secret laptop/notebook computer -- aka, "The Book of Life" -- he's retrieved from its hiding place in a bus-station locker numbered 666. The Almighty has a team of lawyers here below (led by D.J. Mendel, future star of Hartley's Meanwhile), all ready and salivating to earn their fee by consummating the long-standing, dreadful Christian deal, but they turn off Jesus just as much as his run-in with the confrontationally cynical Satan himself; the guy's storied love of humanity, in all its weakness and imperfection, lingers on and keeps giving him second thoughts about this supposedly inevitable judgment day. Dare he defy the apocalyptic prophecy and let humankind continue to exist, grappling and fumbling with good and evil on its own, for at least a while longer? He does, and as we all know, the world didn't end on December 31, 1999 (when we see, in a little montage as encouraging as it is funny, Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and the Devil all joining in together for a celebration of the new year). The film ends on a touching, unexpectedly deep question, with Jesus contemplating the frailty, beauty, and uncertain significance of the human race. Meanwhile, Hartley's swift-cutting embrace of the blurry, quasi-slo-mo effects of the digital video of the time, accompanied by frequent, syncopated bursts of rock and techno on the soundtrack (as well as a heart-stopping moment when Harvey, as Magdalene at a CD listening station, breaks out into a soulful sing-along rendition of "To Sir with Love" as an impromptu reaffirmation of her loyalty to her savior/boss) -- the style, soon to conquer the world in an only somewhat altered form in Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run, that I precipitately dismissed as too slick and MTV-like -- are actually a charmingly naïve, hopeful, open distillation of the hectic pace and seeming technological promise apparently driving us toward the millennium. In framing, composition, and mise-en-scène, it's signature Hartley, with an emphasis on the physicality and movement (and de-emphasis of any emotional "expressiveness" in the intentionally flat-stylized performances) of the people, and precise, sharp, elegant framings whose apparent simplicity belie the rich intricacy of the composition and choreography within.

The great leap forward is Hartley's head-first exploitation of what might seem digital video's decidedly uncinematic, even "ugly" limitations -- the jittery, blurry, not-quite-stable quality of the image's texture, the tendency to exaggerate or otherwise render somewhat "off" the properties of color and light -- as its own new, exciting palette, with its own potential for visual beauty. It would be a digitized path followed, to various kinds of differently exhilarating results, by filmmakers as diverse as Harmony Korine (julien donkey-boy), David Lynch (Inland Empire), and Lars von Trier (who bookended this stage of the digital revolution with The Idiots and Dancer in the Dark). In terms of that revolution, The Book of Life was there at the beginning -- narratively the story of a prophecy happily unfulfilled, but aesthetically holding out prescient predictions of another sort, which by now, in the age of the RED camera and impending DCP dominance, have been well-vindicated, indeed.

To the same degree that The Girl from Monday is a higher-fi work -- the DV technology grew by leaps and bounds between 1998 and 2004, and it's a technologically up-to-date, smoother, shiner affair -- it's also much less optimistic about the future of a technology-obsessed, consumer-corporate culture whose apparent "advancements" represent cruel regressions of the human spirit. The story of a successful but guilt ridden future (M)ad Man (Bill Sage) -- who has been complicit in the now-complete corporate takeover of the U.S. and an accompanying hyper-materialistic, bottom-line obsessed widespread mindset that's had gruesome consequences for sex, love, and education, and who now tries to do his part to undo the damage by acting as an inside agent for a underground counter-revolution that tries to evade the corporate police as it carries out subversive actions like having sex for pleasure (not as a measured exchange of "personal worth" subsequently reflected in one's spending-power accounts) and reading/distributing troublesome books like Walden -- it's nothing less than Hartley's pastiche-homage-update of the dystopian speculative-fiction sci-fi genre as a whole. As Sage's character recruits a sexy, ambivalent coworker (Sabrina Lloyd) to the cause and strategizes anti-corporate maneuvers carried out by a younger crusader (Kids's Leo Fitzpatrick) -- who's of an age and demeanor to also infiltrate the nightmarish new high schools, where kids are sedated with attention-deficit drugs and strapped into virtual-reality "learning module" goggles -- the vigilant monitoring of sexual activity and spending power are exactly Orwell's 1984, only with Big Brother updated as a corporate-governmental all-seeing, all-powerful, tyrannical entity, while the potency of the banned Walden is something straight out of Fahrenheit 451. Even the mysterious, innocent girl from Monday (Tatiana Abracos) -- "Monday" being the familiar name in this now-interplanetary corporate structure for an enemy star inhabited by amorphous, pure-consciousness beings who sometimes send a representative to Earth in search of a wayward son of Monday who got stranded on our planet years ago -- is a female Man Who Fell to Earth, arriving with an iconic (and, it has to be mentioned, beautifully shot) splash, her human guise one of a beautiful naif unwittingly putting herself in danger of becoming too attached to treacherous humanity, thereby making any return back home impossible.

The pastiche isn't limited to the story elements: The visuals, rhythms, and tones of The Girl from Monday rip generous pages from the book of intellectual/"sci-fi" French films of the '60s, with its de-familiarization (through canted angles, stark mise-en-scène, and other simple distortions/manipulations/modifications of videography, production design, and costume) of locations that are obviously contemporary repeating resourceful, audacious trick Godard pulled off with Alphaville, while a frequent use of successive still frames, accompanied by Sage's disembodied, ruefully recollecting voice-over narration is an always-effective stylistic maneuver borrowed from Chris Marker's La Jetée (as is The Girl from Monday's creepy obscuration-through-technology of the eyes, with that virtual-reality high-school face wear and the single-red-eyed helmets worn by the deadly corporate cops, as an immediate visual sign of the cold dehumanization of the future). More interesting is Hartley's perceptive use of the cool, blank-stare quality of this form of digital video -- particularly in the black-and-white mode that comprises about half of the film -- to liken our position and point of view to that of the all-seeing closed-circuit corporate surveillance state (surely even more obviously relevant at this NSA-menaced American moment than it was when the film was conceived). As enjoyable and skillfully executed as all this is, though, there's not nearly as much new being done here as was attempted in The Book of Life; the continuing relevance of The Girl from Monday's ideas is undeniable, but their familiarity, and the well-trod path of cinematic references generally used to express them, intermittently seems to have a distancing effect other than the one intended. It is, however, made stronger through contrast as the second half of a double feature with The Book of Life, reinforcing the wisdom of the pairing of the two pictures on this DVD edition; what might otherwise have seemed an interesting, engaging, but overall slight filmmaking exercise has its motivations and rationale clarified in context, its truer worth revealed not as a stand-alone gesture but as one part of a whole, one necessary step on an artist's continuing creative, philosophical, and technological journey.

Video:

The Book of Life is presented in a letterboxed-widescreen, non-anamorphic (despite the mislabeling as "anamorphic") aspect ratio of (which is fitting, given its lower resolution, the relative primitiveness of its DV technology, and the fact it was made for television in an era where square, not widescreen, TVs were still the norm) and looks quite good for what it is, which is a purposely blurry digital-video production meant, as mentioned above, to highlight the hybrid cinematic/particularly digitized visual properties at the beginning of the digital-video revolution. A little haloing/edge enhancement can be discerned, but otherwise, the intended, sometimes gritty/lurid picture-quality properties of the source movie seems to be nicely intact.

The Girl from Monday is presented widescreen-anamorphic at an approximately 1.78:1 aspect ratio, and, like The Book of Life, is a faithful representation (and aesthetic exploitation) of digital-video technology of the time (a few years, it's worth remembering, before the RED and similar high-end cameras introduced the high-definition great leap forward in digital-video filmmaking), and the picture quality is as high as the source allows for -- notably less blurry than The Book of Life, with only a little haloing/edge enhancement and nice, bright colors, vivid contrasts in the black-and-white portions, and an overall nice feel of clarity, solidity, and depth.

Sound:Both The Book of Life and The Girl from Monday are presented with Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo soundtracks that retain all of the range, depth, and clarity of each film's uniformly well-made sound, with all dialogue immediate- and resonant-sounding, all music detailed, and other sounds (from street noise to a doom-harbinger plane in The Book of Life or wind and waves in The Girl from Monday) clearly audible, for a full, faithful, well-mixed aural texture unmarred by any distortion, imbalance, or muffling.

--"Upon Reflection: Making The Book of Life," a 12-minute short documentary featuring 2005 interviews with director Hartley and actors Martin Donovan and Thomas Jay Ryan (at that point Hartley regulars, the two commiserate on their separate, disorienting first gigs with Hartley, Donovan's in Trust and Ryan's in Henry Fool) about the conception -- in particular the then-controversial, iffy idea of using digital video -- making, and playing of The Book of Life.

--"The Making of The Girl from Monday," a 20-minute documentary that alternates behind-the-scenes footage of Hartley, the crew, and the actors on set in preparation and during shooting (it's fascinating to watch Hartley choreograph his visuals and his actors), as well as interviews with Hartley and actors Bill Sage, Sabrina Lloyd, Leo Fitzpatrick, and D.J. Mendel, all put together in a style that, like the film itself, celebrates the shooting and editing possibilities of digital video.

--The Sisters of Mercy (2003, 16 min.), a short film starring Hartley regular Parker Posey and Girl from Monday star Sabrina Lloyd, with Hartley giving direction from off-camera as the two actresses do various line readings and improvisations (one featuring a hypnotically repetitive recitation of lyrics from The Breeders' "Iris") that take on an incantatory quality as phrases are repeated and characters slipped in and out of. It's ultimately an interesting, if fairly overextended, riff on some embryonic characters/scenarios, more of a self-reflexive scrapbook than anything cohesive.

--Trailers for both The Book of Life (newly created for the film's re-release) and The Girl from Monday (the original trailer).

Six years and big shifts in technology divide Hal Hartley's first two full-length digital-video works, 1998's The Book of Life and 2004's The Girl from Monday, but their pairing on this new DVD release is as thematically/aesthetically apt as Hartley's own insightful use of still-developing DV technology to approach the immediate-future worlds explored in each of the films. They're two sides of the same where-are-we-headed? coin -- The Book of Life's ultimately optimistic, humanistic, droll 'n dry retelling (and hopeful revising) of the fearsome End of Days story from Christian mythology the happier version of a human future laid out in much scarier, technologically/consumeristically zombified, Orwellian terms in The Girl from Monday -- that complement each other quite nicely as a double bill (though The Book of Life is the objectively better and more interesting of the two efforts). Neither film is perfect or quite reaches the heights it's aiming for, but both are very worthy stretches for Hartley, who's rightly better known for his equally philosophically-minded but more quotidian-set cinematic tales of contemporary American life. His unique, arch and cool yet tender sensibility still runs richly through this unfamiliar territory, making for two more minor manifestations of his gift that, while not always as powerful or artistically successful as his greatest efforts, are never anything less than bold, bracing, fascinating stuff. Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||