| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Poem Is a Naked Person: Criterion Collection, A

The Movie:

In 1972, silver-haired rock star Leon Russell and his record producer/business partner Denny Cordell hired Les Blank to make a film. After the twin box office successes of Joe Cocker's Mad Dogs and Englishmen and The Concert for Bangladesh, both of which helped put Leon on the map, it seemed natural to make another film with Leon now at center-stage. When Blank finished A Poem Is a Naked Person two years later, he turned it over to his bosses and left the country to take a break. When he came back, he expected to be catapaulted into a new level of prestige in the film business. Instead, he found himself caught in the middle of a messy business divorce. Denny Cordell, who liked the film, no longer held any rights to it; Leon Russell, who had often been annoyed by Les Blank during shooting and didn't like the finished film, owned it all. Unsurprisingly, Leon buried what he had. As part of their contract, Les Blank got a print he could screen at non-profit events, but otherwise the film pretty much disappeared.

Over the years, Blank came to realize that, even though A Poem Is a Naked Person was just a work for hire, it might also be his magnum opus. As he would show it at these one-off non-profit screenings over the years, he would find spots in the film to refine and re-edit. He was re-cutting it as late as 2011, two years before his death. In the Blu-ray supplements, Blank's son Harrod says that one of Les's final wishes was that A Poem Is a Naked Person be restored and remastered. Harrod did better than that: he got in touch with Leon Russell and convinced him to allow the restored film to see the light of day. Janus Films gave the movie a nice arthouse-and-VOD run in 2015 and now the Criterion Collection, who put out the vital box set Les Blank: Always For Pleasure, are responsible for an equally essential home video release of this missing puzzle piece in Les Blank's filmography.

Watching A Poem Is a Naked Person now, it's easy to see why Leon Russell didn't like it. For starters, the film isn't really about him, at least not in a conventional sense. Anyone who has seen Les Blank's earlier musician portraits, The Blues Accordin' to Lightnin' Hopkins and A Well Spent Life with Mance Lipscomb (both included in the Always For Pleasure set), knows that he tends to take a holistic approach to his subjects, focusing as much on the community around the artist as on the artist himself. That approach is amplified by a factor of ten in Poem. We get scattered electrifying moments of Leon Russell in concert, and we get glimpses of him in the recording studio, working on his album Hank Wilson's Back, but we get relatively little interview footage. Instead, Les puts heavy focus on Leon's neighbors and collaborators and friends and employees, which makes the ostensible star attraction a jumbled-up element within the kaleidoscopic whole rather than its obvious center. Hell, Leon doesn't even show up onscreen until around five minutes into the movie.

There are practical reasons for this. Leon became hesitant to submit to interviews after a certain point, a choice which makes him feel opaque and elusive even in his own film. (The palpable onscreen friction between Les and Leon probably had more than a little to do with this.) And so, A Poem Is a Naked Person ends up being less about getting to know Leon Russell and more about what it is like to be a filmmaker spending two years hanging out in Oklahoma in the general vicinity of Leon Russell.

That might sound like an unpleasant bait-and-switch, but in fact, the film's attempt to evoke Leon Russell's world in this oblique way is surprisingly effective and transcendently... well... poetic. By not getting caught up in hagiography or mythology -- or even biography -- Les creates an impressionistic collage that finds the mystical in the mundane, drawing unexpected meaning from its images and juxtapositions. The most notable instance of this is Les's choice during one sequence to take footage of Leon in concert and intercut it with a group of people gathered to watch a building get blown up. If that isn't puzzling enough, he then also throws footage of a snake devouring a baby chick into the mix. The film is pleasantly random in general, but these choices feel particularly pointed -- and maybe Leon thought they were pointed at him. Maybe they were. But, when Les shows us the aftermath of the demolition, with onlookers picking through the rubble of the blown-up building, in search of pieces to take home, and then he shows us a post-concert meet-and-greet where Leon is mobbed for autographs and kisses, the critique seems lobbed more at the weird cultural desire to own a piece of things, whether they be destroyed landmarks or rock singers.

One of the benefits of hanging out in the vicinity of Leon Russell is that tons of other musicians float in and out of that vicinity too. George Jones stops by Leon's studio, and does an impromptu solo acoustic rendition of "Take Me." A pre-superstardom Willie Nelson pops up twice, doing "Good Hearted Woman" by request in an honest-to-goodness honky-tonk and later performing bluegrass with "Sweet Mary" Egan at an outdoor festival. Eric Andersen gets into a minor argument with Leon about what's more important: yammering to the movie cameras or recording an organ part for Andersen's new record. There's also wonderful footage of Leon recording a version of "Goodnight Irene" for the Hank Wilson album, with Charlie McCoy on backing vocals and harmonica.

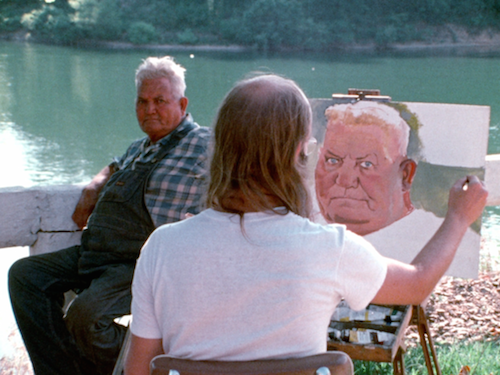

There are countless memorable images in the film, whose beauty and strangeness are magnified by the fact that they arrive with little to no context. Shirtless, bearded artist Jim Franklin walks around an empty swimming pool, collecting errant scorpions before painting a psychedelic seascape on the pool walls. A parachuting competition official toasts the camera and then tries to eat the beer glass; he succeeds on take two. A farmer throws geese off the back of a truck to an assembled crowd, hoping to catch the fowls like the bouquet at a wedding. A young woman freaks out at the size of a giant caught catfish.

I must admit that, on first viewing, I was a little confused by A Poem Is a Naked Person. Even as a huge fan of Les Blank's work, I initially felt like he let his instinct for people-watching overwhelm everything else. I decided to give the film a second watch a few days later, and it immediately clicked for me. Maybe because I had stopped worrying about who exactly each person onscreen was, I got on the film's wavelength more easily, and the cumulative power of the film's vignettes revved me up to the point where I was giddy by the end. Les's editorial choices began to make perfect sense, and I realized how A Poem Is a Naked Person actually is a film about Leon Russell -- even when it's not.

The Blu-ray

A Poem Is a Naked Person comes packaged with a color fold-out, including an essay by Kent Jones.

The Video:

As with the Always For Pleasure box, the AVC-encoded 1080p 1.33:1 transfer here is surprisingly good. These Les Blank films are head and shoulders above the vast majority of films shot on 16mm I've seen brought to Blu-ray in the past few years. Admittedly, the overall look is not pristine. It is grainy and gritty, and it has a few moments of minor damage. I would argue these are textural benefits, however, and the overall depth, clarity, and vividness of color goes above and beyond reasonable expectations.

The Audio:

The LPCM mono audio is well-preserved but predictably influenced by the situations in which it was recorded. Certain passages get a touch muffled, and there appear to be some phase issues during a few of the concert scenes. Nothing too abrasive. The disc offers one subtitle option: English SDH.

Special Features:

(HD, 26:40) - A new piece recorded with director Les Blank's son Harrod and Leon Russell, in which they discuss why Leon decided to keep the film out of circulation and how Harrod was able to convince him to reverse his stance.

Final Thoughts:

Long story short: we should all be grateful that Leon Russell changed his mind and let this film be widely seen. It's a bizarre but beautiful collage that puts formulaic rock docs to shame. DVD Talk Collector Series.

Justin Remer is a frequent wearer of beards. His new album of experimental ambient music, Joyce, is available on Bandcamp, Spotify, Apple, and wherever else fine music is enjoyed. He directed a folk-rock documentary called Making Lovers & Dollars, which is now streaming. He also can found be found online reading short stories and rambling about pop music.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||