| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

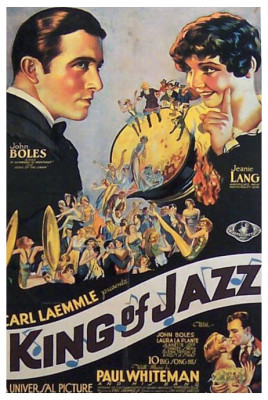

King of Jazz

One film, however, languished in unrestored obscurity until now. Universal's King of Jazz (1930), while in small ways just as dated and clunky as the revues made by Paramount, MGM, et. al. overall is far superior. Indeed, it's chockfull of great music, ambitious special effects, stunning production design and costumes, superb two-strip Technicolor cinematography, some amazing specialty acts, and from a historical standpoint it's unquestionably priceless.

The plotless film is built around the music of orchestra leader Paul Whiteman, the self-styled King of Jazz. As commentators on Criterion's new Blu-ray frequently point out, the term "jazz" in 1930 referred to virtually any non-classical form of popular music, though particularly jazz-influenced dance music. Whiteman's band/orchestra fused syncopated dance music, jazz, and symphonic music in a manner virtually in opposition to the sounds of concurrent African-American jazz pioneers, Whiteman's music built around intricate arrangements versus the free-form style of the "true" kings of jazz as we look back upon the genre today.

Whiteman and his orchestra were one of the biggest radio and recording stars of the era, but in the decades that followed Whiteman's role in the development of jazz was unjustly maligned, his once towering reputation greatly tarnished and diminished. In the eyes of jazz purists, he was to the 1920s what Pat Boone was to rock-and-roll in the 1950s, an unfair assessment. As late as Ken Burns's PBS documentary series Jazz (2001), white man Whiteman is portrayed almost as a villain, a cultural appropriationist usurping the King of Jazz title from the form's true heirs, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington.

And yet, as the supplements accompanying the disc make clear, Whiteman's music simply followed a path different but no less innovative than his era's African-American artists. It was, for openers, Whiteman who commissioned and introduced George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, the emblematic work of symphonic jazz, one of the greatest pieces of music of the entire 20th century. Another of Whiteman's legacies was in hiring, nurturing and showcasing many of the best jazz performers of the day, notably coronetist Bix Beiderbecke, saxophonist Frankie Trumbauer, jazz violinist Joe Venuti, jazz guitarist Eddie Lang and, as vocalists, The Rhythm Boys, featuring a young Bing Crosby on the cusp of mainstream stardom. All but Beiderbecke appear in King of Jazz.

The supplements also point out that, while Whiteman's band may have been entirely white, his arrangers were among the top African-American artists of the day, and Whiteman himself lobbied for an integrated orchestra, but ran afoul of management and impresarios nixing that revolutionary idea: an integrated band wouldn't have been able to tour in 1920s America. Whiteman himself, physically suggesting a dapper, hipper Oliver Hardy, himself comes off as charming and playful throughout King of Jazz.

Ultimately, great music is great music regardless of the skin color of those making it, and the music in King of Jazz is really phenomenal. While very little of it comes close to true jazz in the modern sense, a "Meet the Boys" segment offers outstanding solo and multi-artist turns featuring Harry Goldfield (trumpet), Venuti, Lang, Mike Pingatore (banjo) and, on piccolo, Roy "Red" Maier. A later segment has Wilbur Hall dazzling with a performance of "Pop Goes the Weasel," all the while juggling his violin and bow with the dexterity of W.C. Fields.

Other musical highlights include the crowd-pleasing "Happy Feet," performed by the Rhythm Boys and The Sisters G., a German-accented sibling act, the pretty ladies sporting Louise Brooks-styled bobbed haircuts. Rhapsody in Blue, featuring more or less the original 1924 orchestration (the more familiar symphonic arrangement came later, in the early ‘40s) with most of the same musicians that unveiled it in its inaugural performance.

Some of the musical segments have zero connection to jazz, resembling other studio's early musical revues and, while more conventional, offer pleasures of their own. "My Bridal Veil" is pretty hokey stuff, but its colossal set, supposedly the largest soundstage set built up to that time, is positively staggering, as is the football field-size bridal train worn seen at the end of the segment, on a set foreshadowing the one highlighted in Powell & Pressburger's great A Matter of Life and Death. That segment and "It Happened in Monterey," featuring Universal star John Boles (Rio Rita, Frankenstein) also make outstanding use of early two-strip Technicolor, which is notably subtler than Hollywood's penchant for garish primaries in the three-strip process that soon followed.

Interspersed with all this is a selection of novelty acts from a dying Vaudeville, but these wow in their own way, like the acrobatic, limb-contorting dancing of Marion Stadler and Don Rose in the "Ragamuffin Romeo" segment. The comedy bits, almost like prehistoric Laugh-In blackout gags, dominated by William Kent, Slim Summerville, cute-as-a-button Jeanie Lang, and a young Walter Brennan, consist mostly of mild pre-Code type double-entendres. Brennan is so young compared to what audiences are used to that, amusingly, in one of Criterion's featurettes a still of the older Summerville mistakenly identifies him as Brennan.

In other respects, King of Jazz anticipates, slightly, Universal's first horror cycle, featuring as it does outstanding special visual effects, including Whiteman's entire band in miniature emerging from a tiny valise and other trickery. A brief but incredible shot has dancers appearing like happy-go-lucky Godzillas in a vast miniature cityscape.

Video & Audio

Criterion's Blu-ray of King of Jazz, presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1, utilizes a 4K restoration done by Universal, using the original 2-strip Technicolor negative and three surviving prints, mostly, apparently, for segments cut for reissue later in the ‘30s. The image quality fluctuates, sometimes even within a single shot. The worst-looking film elements are what audiences expect from 2-strip Technicolor films on releases like Mystery of the Wax Museum but a lot of it is among the best 2-strip has ever looked on home video, and it really dazzles. The process was great with reds and greens but true blues and yellows were pretty much impossible. The color pallet takes a little getting used to but at its best really looks sharp. Intriguingly, the two-strip releases seen in the past tend to accentuate the heavy makeup actors were required to wear but, somehow, this is much less noticeable on the pristine footage. The mono soundtrack, remastered from a 35mm optical negative, is quite good for its era. English subtitles are provided and the disc is region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

Criterion really deserves credit here, for packing this release with genuinely worthwhile, enlightening supplements that greatly enhance the value of this release. They include: about six minutes of footage in four segments of footage used in the re-release version only, including altered opening titles. Michael Feinstein and Gary Giddins appear in new interviews discussing the film, Whiteman, the featured musicians, and the songs and songwriting. These two segments are really interesting and highly informative. James Layton and David Pierce, authors of a making-of book about the picture, present a series of video essays describing the film's production. All Americans (1929) offers an earlier version of the "Melting Pot of Music" done on a much grander and audacious scale for King of Jazz; I Know Everybody and Everybody's Racket (1933) is an amusing short subject featuring Whiteman and Walter Winchell. Both shorts are in pristine shape. Two Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons feature Whiteman and adapt footage initially animated for King of Jazz. An great audio commentary features Giddins, music critic Gene Seymour, and musician Vince Giordano. Finally, there's an especially good booklet essay by Farrah Smith Nehme that intelligently encapsulates all the charms of King of Jazz while offering good background information.

Parting Thoughts

One of the best Blu-ray releases of 2018, King of Jazz is a DVD Talk Collector's Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||