| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Sacha Guitry: Four Films, 1936-1938

The films don't at all resemble the works of other pre-war French masters. The first three movies are generally static and claustrophobic film adaptations of Guitry plays, offset by their wit and the performances, especially by Guitry, playing the lead in each. The earliest and most famous of the batch, The New Testament (1936), is quite entertaining, and I'd enjoy watching it again with native French-speakers to gauge their reactions. But as I worked my way through the set, I gradually found a little of Guitry's screen persona goes a long way. Blessed with a great speaking voice, he's witty and literate, but also comes off as flamboyant and a little smug and condescending. Even his admirers note his amusing but appalling misogyny, material decidedly un-PC by today's standards.

That didn't bother me so much as Guitry's wearying style, of locking the camera down and confidently betting everything on his admittedly fine leading performances. The last and most anomalous title, Let's Go Up the Champs-Élysées (1938) is contrastingly fast-paced and more visually oriented though in the latter sense not very well directed. Like the other three, it has its plusses and minuses.

The New Testament (Le nouveau testament, originally released in English as Indiscretions, 1936) gets the set off to a great start. Adapted by Guitry from his play, since remade multiple times in France and elsewhere, is a comedy more of less of the same school as Ernst Lubitsch and (later) Billy Wilder, densely packed as it is with sharp, witty dialogue that travels surprisingly well. The excellent English subtitles make all the difference.

Guitry, plays a late middle-aged physician, Jean Marcelin, who runs a private practice out of his swanky Parisian apartment. The movie opens with some amazing (from a historical perspective) stolen footage shot in cars and on the streets of pre-war Paris, revealing that Marcelin's wife, Lucie (Betty Daussmond), has been having an affair with Fernand (Christian Gérard), the medical resident son of their best friends, the Worms (Charles Dechamps and Marguerite Temply). Despite her own indiscretions, she becomes jealous when he hires a new and much more attractive secretary, Mademoiselle Lecourtois (Jacqueline Delubac). Prior to a dinner party with the Worms, Lucie treats her husband's new secretary with open contempt and, unexpectedly, she returns the insults in kind.

Marcelin fails to show up for dinner, but his dinner jacket mysteriously turns up, returned by a bearded man resembling Victor Hugo. Insatiably curious and perhaps concerned that Marcelin made have committed suicide, Lucie, Fernand, and the Worms check the pockets and find a sealed envelope containing Marcelin's Last Will and Testament. Upon reading it, all Hell breaks loose.

Guitry breaks up the staginess - nearly the entire plot occurs within the Marcelin home - with a few locations scenes, and while those are certainly interesting, the filmed-play aspects really don't impact the enjoyment factor of this delightful farce. The film is talky, yes, but the talk is sharp and funny, with the long, dense and prolix dialogue of Marcelin particularly recalling James Cagney's performance in Wilder's One, Two, Three (1961). Typical is a very early scene in which Marcelin has a long talk with his butler (Louis Kerly), who garrulously seeks his new employer's approval, and they have a long chat about choosing an appropriate name to address the new domestic.

Guitry, presumably armed with the advantages of playing the role on the stage, gives a marvelous performance, while Kerly and Temply stand out also. Delubac, then 29, was Guitry's wife and she's generally fine, though her speaking voice records oddly nasally in this production, filmed at Paramount Picture's Parisian studios.

Mainly though, the picture is quite funny with multiple unexpected plot twists and amusing characters. The smart screenplay has many interesting observations about love, marriage, and infidelity, going so far as to argue that security is no substitute for passion, and that a love without passion is a far worse punishment than the consequences of an extramarital affair looked back on with great affection.

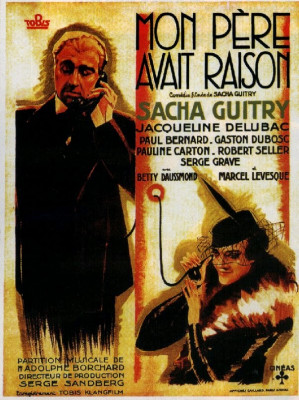

My Father Was Right (Mon père avait raison, 1936) is less satisfyingly amusing but in some ways more ambitious. Again based on Guitry's play, the movie has him playing inattentive father Charles Bellanger to son Maurice (Serge Grave), a boy obviously longing for his father's approval. When his wife calls from the train station, informing Ballanger that she's leaving him for a (presumably) younger man, protective paternal instincts immediately click in. No longer will Maurice be forced to leave home for boarding school: he will raise the boy himself, imparting upon him all that he knows.

By the time Maurice is an adult (and now played by Paul Bernard), his brain is filled with knowledge but he's also cripplingly distrustful of all women, certain they will lie and abandon him, like his mother had done. This creates a serious problem for Maurice's devoted girlfriend, Loulou (Jacqueline Delubac again), eager to consummate their relationship during a trip to Venice, but he's reluctant to leave his father's side.

Comparisons of Guitry and the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu seemed ludicrous until I saw this, which has unmistakable if distant-cousin parallels. Ozu's movies are very often about lonely, aging parents selflessly devoted to children who either don't appreciate them or are resistant to leaving them to marry and have families of their own. My Father Was Right is a decidedly Gallic take on this concept. Where the elderly parents in Ozu's parents are resigned to physical decay and loneliness because that is the natural order of things, Guitry vision is entirely different.

As a younger man Ballanger had been nonplussed by his own father's (Gaston Dubosc, a role played on the stage by Guitry's actor father) eccentricities, casting off the moral standards of middle-aged men of responsibility and delighting in becoming an inveterate liar. As Ballanger becomes older he finds himself inevitably falling in his father's footsteps, shedding all pretentions and generally living by the aphorism carpe diem. The servants and Maurice are alarmed by Ballanger's stark turnabout, believing that he's losing his marbles.

Even more than The New Testament, My Father Was Right feels very much like a filmed stage play, and it so rarely leaves Ballanger's study that, at the end when several characters walk up a flight of stairs just beyond a door it's almost startling as the movie audience hadn't seen other parts of the house. As before the acting is generally excellent, particularly Guitry, Dubosc, and Betty Daussmond, again playing the wife character. Guitry is especially fine in the picture's many one-on-one conversations, typically played at a breakneck pace that it's reminiscent of burlesque-style comic patter, or Japanese manzai comedy.

Serge Grave is exceptionally good as the tenderhearted, younger Maurice. When Paul Bernard turns up as Maurice as an adult it's a bit disappointing. He resembles Grave not in the slightest, and is irritatingly whiny and wimpy, though partly that's the character.

Let's Make a Dream… (Faisons un rêve...1936) is yet another Guitry gabfest. Though only about 70 minutes, Guitry speaks enough dialogue for three movies. This is all the more impressive when you consider this is essentially is a one-act comedy padded, charmingly so, with an on-camera overture, a musical encore, and a lengthy, all-star comic prologue.

After two numbers performed by the Orchestre Tzigane (apparently a French-Romani group), the second number performed under the opening titles, the musicians are revealed to be performing at a dinner party, the various gossipy socialites all played by big French stars, among whom Arletty, Michel Simon, and Claude Dauphin were most recognizable to me. The roving camera catches amusing little blackout-type dialogues, each rarely more than a minute long.

After this comes the main story: "The Lover" (Guitry), a man of leisure at the party has invited "The Wife" (Jacqueline Delubac) and her "Husband" (Raimu) to a 3:45pm appointment at his luxurious apartment. The couple has no idea why they've been invited, and he's annoyed when the man isn't there at the appointed time. The Husband has a 4:00 appointment with a "South American" elsewhere, supposedly regarding business, but which the wife clearly suspects is an illicit rendezvous. Frustrated, the husband leaves.

Soon after, the Lover emerges from the bathroom where he'd been hiding all the time. He confesses his love for the Wife, and she reciprocates, they promising to meet up for their own session of lovemaking later that evening. After a long telephone conversation between them (telephone monologues being a Guitry specialty), she arrives but they oversleep. How can she return home without the husband finding out?

Those not enamored of Guitry's style will find Let's Make a Dream… the most taxing of the four films in this set. As the Lover, Guitry is over the top with French lover passion, overcome with anticipation as he reveals his feelings to the Wife, then later anxiously awaiting her arrival. On one hand it captures the spirit and excitement of blossoming romance, but Guitry's already prolix dialogue and gesturing is really supercharged here, to the point of becoming wearying, even as I admired his performance and energy.

The fine music at the opening and the more kinetic prologue only underscore how everything grinds to a halt visually as the movie returns to more familiar Guitry territory for the last hour, confined to a set even more cramped than the last two pictures. I didn't time the long takes but some of the single, generally static shots seemed awfully close to running a full 10 minutes.

Let's Go Up the Champs-Élysées (1938) begins in the present day, ominously almost a year to the day before the start of World War II in Europe, with schoolmaster Guitry forgoing a boring math lesson to instead entertain his boys (one of whom, intriguingly, is black) with a series of historical anecdotes about his beloved Champs-Élysées, from its beginnings as little more than a dirt path through a forested Paris.

The bulk of the picture alternates between a bit of historical footage of the famous boulevard, outdoor scenes, and more talky bedroom farce here laced with political intrigue and maneuvering. Unlike the three earlier films, this offers considerably more camera movement, exteriors, and shorter cuts, some of it self-consciously arty but spatially disorienting.

It couldn't have been cheap. The long takes and pre-staged earlier films were shot in a matter of days for very little money, but Let's Go Up the Champs-Élysées is awash with extremely elaborate period costumes, wigs, and makeup, in sequences populated with extras, period coaches and historically accurate props and sets, and there are even a few matte paintings and other special effects.

As it follows several generations of French royalty and other pre- and post-Revolution elite, an extensive knowledge of French history is almost a must.

Video & Audio

Arrow's Sacha Guitry: Four Films, 1936-1938 is a handsomely designed set, with all four movies licensed from Gaumont for a limited edition (1,500 copies) which includes standard-def DVDs. Considering their age and despite some minor imperfections, notably a strange, chemical-like blotching appearing on My Father as Right, the full-frame black-and-white films generally look very good. The LPCM uncompressed 1.0 mono audio is also fine, this despite Guitry's aversion to looping offscreen dialogue: he tends to let the on-set recording stand as it is, which at times comes off badly. Region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

The many supplements really add to the viewer's understanding and appreciation of Guitry's talents. The three booklet essays are more on the esoteric cinema journal side, but the Ginette Vincendeuu's filmed introductions and selected scene commentaries are very enlightening. Philippe Durant provides four video essays, and there are interviews with director Francis Veber and filmmaker Pascal Thomas. Also included is a long French trailer for Let's Make a Dream along with sound tests.

Parting Thoughts

Fruitful if a bit wearying if viewed one after another, Sacha Guitry: Four Films is an excellent boxed set that's Highly Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||