| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

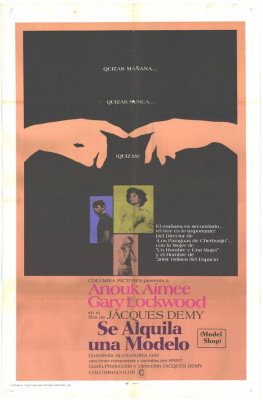

Model Shop

Demy established his reputation in a series of films simultaneously lushly romantic and harshly realistic about love and the desire for lasting relationships. After Lola (1960) and Bay of Angels (1962), Demy began to interest Hollywood with The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), big commercial successes in Europe and, Umbrellas particularly, critically lauded. With his filmmaker wife, Agnès Varda, Demy spent a few years in Hollywood, each armed with a development deal from a major film company. Model Shop was inexpensive, made for around $1 million or less but its backers, Columbia Pictures, hadn't a clue how to market such a delicate, unusual film.

The film chronicles 24 hours in the life of unemployed young architect George Matthews (Lockwood), who lives in a rundown rented house near South Venice Beach with his girlfriend, aspiring actress Gloria (Alexandra Hay). They wake up to find George's vintage MG about to be repossessed but he talks the finance company into giving him until the end of the business day to come up with a $100 payment so that he can keep his wheels.

The first part of the picture follows George as he hits up various friends (including members of the rock band Spirit, playing themselves) for the money he needs. As he unsuccessfully tries to borrow money from a parking attendant friend, he sees a beautiful French woman, Lola (Aimée, reprising her title character from Demy's 1960 film), leaving the lot in a white convertible. He follows her to a mansion above Sunset Blvd., and later to a tawdry "model shop" where johns, given a camera and a roll of film, take erotic photos of the scantily dressed women working there. George arranges a 15-minute session with Lola, but nothing comes of it.

Later, some friends running an alternative newspaper offer George work, but then he receives word from his estranged father that he's been drafted into the army, and must leave for his hometown of San Francisco the following morning. For reasons even he can't fully understand, this makes George more desperate than ever to establish some sort of meaningful relationship with Lola, a veritable total stranger.

Movies in which Los Angeles is so integral to the mood tend to depict the city in a similarly glamorous fashion: landmarks like the Hollywood sign, the Capitol Records building, Grauman's/Mann's Chinese Theater, picture postcard shots of the beach, etc. are prominently featured, as is the city's most striking/unusual architecture. Demy eschews all that. Instead, his focus is almost entirely on the bland urban sprawl, the drab, slightly decaying thoroughfares with their one- and two-story storefronts. No landmarks of any kind are ever glimpsed. Even though George lives within spitting distance of the beach, that view is always obscured by an oil pumper parked on his doorstep, its constant churning almost mocking George's poverty. Even during the two brief visits high above Sunset when George spies on Lola and her mysterious visits to the mansion there, Demy deemphasizes other adjacent mansions and George only briefly enjoys the incredible view they afford.

Probably more than a third of the film consists of George getting in and out of his car (methodically starting the ignition and turning on the radio), riding along with him as he cruises the streets, or shots of Lola driving around in her car. Yet, instead of being boring all this driving around is somehow fascinating. Perhaps it captures one facet of LA living so well: the enormity of wasted time navigating the streets in order to accomplish so very little.

By design, George is not a very sympathetic character. He's an arrogant slacker, inexperienced yet expecting all to recognize his great if completely unproven talent. Unhappy at the prospect of having to prove himself, he simply quits his last job and bums around, aimless and broke. His girlfriend, more determined but no more realistic about her career chances, is unhappy with their arrangement but reluctant to leave him without anything better on the horizon. George's obsession with Lola isn't sexual or even romantic, but rather the actions of a desperate young man grasping for a lifeline as his world slowly crumbles around him. Maybe he can talk this stranger into some kind of meaningful if fleeting relationship that might somehow validate so many wasted months of fruitless drifting. Beating out an unknown Harrison Ford for the part, Gary Lockwood, so perfect as the blandly handsome, humanity-drained astronaut in 2001, is likewise excellent here as the quiet, outwardly too-casual but inwardly tormented George. He's hardly a role model, and yet his final moments in the film generate considerable unexpected heartache on several levels.

Long before big movie franchises created labyrinthine "cinematic universes," Demy (with Varda) interlocked most of their early films with frequent references to characters from their other movies. This extends to Lola considerably, but viewers unaware of the many connections to Demy's earlier French films aren't really missing anything. Where the picture does falter is during its last third when Model Shop, up to that point much more visual than verbal, becomes unnecessarily talky, with Lola explaining her backstory while George's lines more obviously sound like dialogue written by a Frenchman for whom English is a second language. These later scenes would probably play just fine in a French language film of the period, but sound a little "off" in a Hollywood production.

Some viewers might find the methodical pacing of Model Shop boring, but it generates an air of authenticity in little ways lost on conventional movies. For instance, at the beginning of the film, Gloria is seen preparing a breakfast tray of toast, coffee and juice, which turns up later near the end of the film, sitting half-consumed, cluttering the kitchen counter. It's a small touch, but it reminds the viewer of what came before and of how much time has passed since.

Alexandra Hay, like Lockwood, plays Gloria in a similar manner, she only slightly more ambitious than he is. In her film debut, Hay managed to look thoroughly bored as a carhop taking an order from Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967). Appropriately, she's fairly attractive, kind of a cross between Thelma Todd and Twiggy, but lacking the sort of blazing screen presence to believably "make it" in Hollywood, like so many hundreds of thousands of other aspiring actresses. For her part, Anouk Aimée is quite the opposite, strikingly beautiful though her performance suffers a bit being entirely in English.

Pal and colleague Cinesavant found many of the same plusses and minuses with Model Shop, though I disagree with his assertion that the model shop itself is not realistic, that such a venue would have been a veiled front for explicit prostitution. Maybe, but according to the exhaustively researched series The Deuce, "message parlor"-type venues really didn't come into widespread existence until sometime in the early 1970s, while during the ‘60s there were definitely places like that depicted in Model Shop where horny men would go and take pictures of nude and semi-nude women. Those scenes in Demy's film don't quite look right mainly because they were clearly shot on a soundstage whereas the rest of the picture, interiors and exteriors, were filmed on location, in real buildings (except Lola's apartment, which also looks like a set).

Lola's trip up into the hills above Sunset Boulevard is never explained, though the implication certainly is that she might be prostituting herself to wealthy clients, which would also explain her expensive-looking wardrobe and convertible, this despite the fact she's trying to save enough money to fly home to France.

Video & Audio

Twilight Time's region-free, 1.85:1 widescreen Blu-ray, licensed from Sony Pictures, looks fantastic, a real you-are-there time capsule of Los Angeles, notably sharp and sporting excellent color and contrast. The 1.0 DTS-HD Master Audio audio is also very good. This is a limited edition title of 3,000 units.

Extra Features

The limited supplements are: a trailer and TV spots that don't do the film any favors; an isolated music track of Spirit's interesting score jumbled in with some classical pieces; and Julie Kirgo's usual liner notes.

Parting Thoughts

Unusual but highly rewarding, Jacques Demy's Model Shop is Highly Recommended.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||