| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

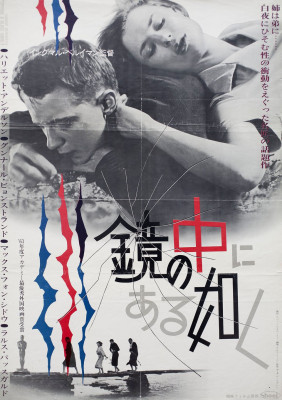

Film Trilogy by Ingmar Bergman (Through a Glass Darkly / Winter Light / The Silence), A

In Through a Glass Darkly (Såsom i en spegel or, "As In a Mirror"), novelist David (Gunnar Björnstrand) arrives at his family's summer home, on a remote island. Already there are his grown daughter, Karin (Harriet Andersson), and 17-year-old son, Minus (Lars Passgård), as well as Karin's husband, Martin (Max von Sydow), a physician.

The family reunion is spoiled when David, having just returned from a long trip to Switzerland, announces that he won't be staying the summer, as he's already agreed to join a group of travelers in Yugoslavia. Minus had been hoping to engage in real conversation with his emotionally aloof "Papa," and Karin's distress is even more urgent: she's recently been released from hospital after being diagnosed with schizophrenia. Martin, aware that her illness is almost certainly incurable, dotes on his mentally fragile wife.

The story is confined to a single evening and most of the following day. Self-absorbed David, unable to finish his latest novel, the latest in a series of best-selling but critically negligible works, considers mining his daughter's condition for source material. Martin confronts him about this, and David reveals that he had attempted suicide in Switzerland, but was saved when the car he intended to send him off a cliff stalled at the last minute. Back at the vacation home Karin's mental state quickly deteriorates: hearing voices coming from the attic, she believes God will appear before her from behind the peeling wallpaper. And while frigid toward Martin, in her schizophrenic episodes she becomes sexually active, turning her attentions toward Minus.

Through a Glass Darkly was the first of many Ingmar Bergman films shot on the Baltic Sea island of Fårö, east of mainland Sweden. (Bergman himself was buried there.) The island and the austere vacation home buildings add enormously to the film's lonely, isolated atmosphere, while helping to pare the film's themes to the bone. A family drama with just four characters (no others are seen), the film is concerned with how each grapples with Karin's mental disintegration and inevitable eventual institutionalization.

Andersson was at first reluctant to accept the role of Karin but Bergman talked her into it, the result being one of the most raw and realistic performances of its kind. (Offhand, only Gena Rowlands in Cassavetes's A Woman Under the Influence matches its brilliance.) As Karin describes it, she's torn between two realities and so traumatic are the shifts back-and-forth she finally feels compelled (after recognizing the consequences of her incestuous flirtations with Minus) to choose, if that's possible, one reality over the other. Martin, being a doctor, intellectually accepts her bleak prognosis but emotionally struggles with her decline anyway, while David believes his suicide attempt resulted in an epiphany where he now loves his family, and comes to believe, so he says, that God exists in the form of love, such as they feel for one another, though Martin seems to think David is merely trying to intellectually justify his own selfishness.

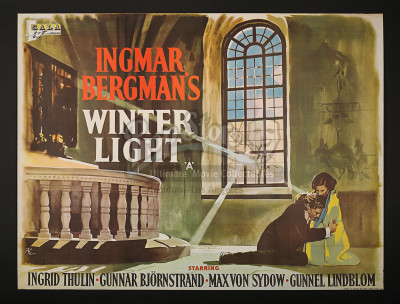

Winter Light (Nattvardsgästerna or, "The Communicants") refutes David's belief that God-is-love, the protagonist in Winter Light (and played by the same actor) quoting David's earlier dialogue exactly.

Tomas (Gunnar Björnstrand) is a pastor in rural Sweden, whose flock has dwindled to almost nothing since the death of his wife and Tomas's growing disconnect with his community. At the noon service, a mere handful of people turn up, including suicidal fisherman Jonas (Max von Sydow) and his distressed, pregnant wife, Karin (Gunnel Lindblom); and Tomas's former mistress, Märta (Ingrid Thulin), an atheist.

After the service Tomas, feverish with a bad cold, meets with Jonas and Karin, she pleading with the pastor to help her husband, he overwhelmed by fear of nuclear war. When Jonas returns to the church alone, Tomas, whose own faith has deteriorated, can provide no comfort, suggesting the world only makes sense if one denies the existence of God.

Tomas also confronts Märta, who remains utterly devoted to her former lover, but he has no love to give her and bluntly, even cruelly tells her so. Then news arrives that Jonas has committed suicide.

(Spoilers) Winter Light's themes hinge on a late scene between Tomas and Algot (Allan Edwall), a sexton at the other small church where Tomas preaches. (No parishioners turn up there.) Algot suggests Christ's physical suffering during the Passion, was secondary to God's silence during the crucifixion. ("My God, why hast thou forsaken me?") In other words, for Algot, God's silence is part of his very existence, not proof of non-existence. The ambiguous ending has Tomas deciding to hold service in the virtually empty church, the viewer left to decide whether Tomas now is certain God does not exist, or that his faith is somewhat restored by the notion that God's silence is a test of one's faith.

In Through a Glass Darkly, Harriet Andersson stunned audiences with her clinical portrayal of a schizophrenic. In Winter Light, Max von Sydow is no less impressive as the far more reticent Jonas, whose turmoil is entirely internalized. He has hardly any lines, his mental state so poor he's unable to really communicate to anyone on any level, this despite a pregnant wife and other children at home, hence his wife's desperation.

Likewise, Björnstrand is enormously expressive despite his seeming coldness. He tells Märta how much he loved his wife, was utterly devoted to her, and Björnstrand convinces the movie audience this is no doubt true.

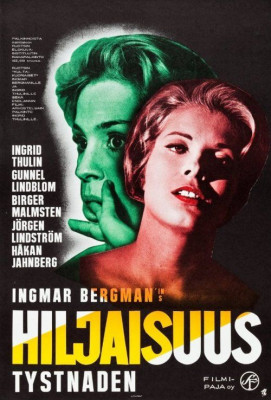

Religion plays no direct role in The Silence, a film in which God seems to have vanished entirely. Set in a fictional Eastern-Europe country on the eve of war, the story follows two sisters and the younger sister's young son during their travels.

Ester (Ingrid Thulin), the older sister, is a literary translator suffering from a never-identified, possibly terminal illness akin to tuberculosis. (In the opening scene she coughs up blood.) The younger, more sensual sister, Anna (Gunnel Lindblom), decides they and her 10-year-old boy, Johan (Jörgen Lindström), shall interrupt their journey home in a town called "Timoka," hoping Ester will recuperate after several days of bedrest, though rolling tanks and other signs of impending war loom outside.

They rent an apartment at a once-luxurious hotel, now bereft of guests save themselves and, as Johan soon discovers, a large troupe of Spanish dwarfs, performers in a touring show. (They seem to be siblings as well, though this Bergman makes no notice of this.) Also about is an elderly porter (Håkan Jahnberg) who is friendly toward the boy. Scenes of Johan wandering the cavernous hotel are not unlike those in Stanley Kubrick's later The Shining.

The Silence is nearly that, not quite a silent film but with minimal dialogue and long stretches of pure cinema. Most of the focus is on the emotionally estranged Ester and Anna, the latter resenting her older sister's prying and judgmental nature, and of caring for Ester through her illness. At times she's up and about, able to work, while at other points in the story she seems on the verge of death. (These latter scenes are genuinely unnerving in their verisimilitude.)

Anna takes advantage of Ester's infirmity to rebel against her weakened sibling by openly exploring her own sexuality: after watching a couple having sex in a theater, she seduces a waiter from a nearby café.

The Silence was Hot Stuff upon release. Viewers may be surprised to learn that, however indirectly, Ingmar Bergman was the father of modern pornography, but it's essentially true. Bergman himself predicted the film would do little business and was shocked to learn that its then-sexual explicitness proved a huge draw for audiences around the world, including Sweden. It opened the floodgates for Swedish erotica that likewise traveled around the world and, hence, evolved into the hardcore porn that followed a decade later.

The brief nudity and more explicit sexual themes, mild by today's standards, distract from the picture's main themes. Partly the film is about communication: suppressed resentment between the sisters, their time in a country where they (and Johan) cannot speak the language, and the workout the movie audience gets trying to make sense of the long scenes with no dialogue, occasionally odd images that don't always make plain what's happening onscreen. The apparently imminent war outside is so totally beyond their control all they can do is look at the growing chaos from their hotel and train car windows.

Ester tries to communicate with the old porter, finding common ground as they share an appreciation of Bach heard over the radio. "Sebastian Bach," says Ester. "Johann Sebastian Bach," replies the porter. A reminder, perhaps, that Anna's son is also named Johan, whose basically innocent, forming personality is able to see, if not exactly understand, those around him. Woody Allen and others have suggested, compellingly so, that Ester and Anna represent two sides of a conflicted, single woman. If that's so one could read the end of the story as Anna abandoning her morally upright side, one attempting to communicate and make sense of the world, for one of total-gratification.

Video & Audio

The 2K restorations by the Swedish Film Institute all look splendid, each film in black-and-white and presented in their original 1.37:1 standard frame. Winter Light is the most pristine, having been sourced from the original camera negative (the other two utilize 35mm inter-positives) but the difference is slight, barely noticeable even on large projection screens. The uncompressed mono audio, remastered from the 35mm optical soundtracks, is likewise excellent, and English-dubbed versions are included as an extra. There's one film per disc, given its own inner cardboard sleeve. The English subtitles are fine and the set is region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

Supplements presumably mirror those previously found in the big Bergman box and on earlier DVDs. They include 2003 introductions by Bergman himself; Ingmar Bergman Makes a Movie, a five-part documentary on the making of Winter Light; 2003 video essays by Peter Cowie; a 2012 interview with Harriet Andersson; audio from a 1962 interview with Gunnar Björnstrand; an illustrated audio interview with Sven Nykvist, the cinematographer of all three films, recorded in 1981; a poster gallery and (Janus Films) U.S. trailers, amusingly dated in their approach to selling "arthouse" titles. A 28-page booklet includes "The Word and the Spirit," an essay by Catherine Wheatley and "God Said Nothing," an excerpt from Bergman's autobiography.

Parting Thoughts

Those unable to fork over the serious cash for the big box o' Bergman now might consider this set, a sampler of sorts, three outstanding films from a master filmmaker. A DVD Talk Collector Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian currently restoring a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||