| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

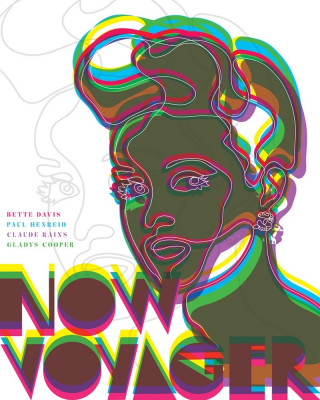

Now, Voyager

Yet, emotionally, Now, Voyager is almost searing with authenticity, the psychological struggles of its protagonist, and later a child she identifies with, resonate with profound earned emotion. Prouty herself suffered from depression and nervous breakdowns, which along with psychological therapy is dramatized here with, by 1942 standards, impressive verisimilitude. In some respects, this may be the most authentic depiction of psychological trauma and recovery in a Hollywood film until at least the early 1960s.

In an interview by Dick Cavett with star Bette Davis, she expresses admiration for the documentary-like realness of movie acting at the time (1971), but admits preferring the slightly more heightened acting style in which she excelled, and in which Now, Voyager certainly falls. It features one of her very best performances.

Many reviews describe Charlotte Vale (Davis) as an "old maid" or an "ugly duckling." But that doesn't begin to describe her real problems. A reclusive woman of about 35, she lives in the palatial Boston mansion of her dowager mother (Gladys Cooper), a ruthlessly domineering, haughty character controlling absolutely every aspect of Charlotte's life: how she dresses, what she eats, what she's allowed to read. Behind Charlotte's locked bedroom door, she sneaks the occasional cigarette and reads books banned from the household, but her tyrannical mother's psychological abuse has pushed her daughter to the brink of a complete mental collapse.

Just in time, sympathetic sister-in-law Lisa (Ilka Chase) brings home, unannounced and unwelcomed, acclaimed psychologist Dr. Jaquith (Claude Rains). It doesn't take long for Jaquith to diagnosis Charlotte's psychological dilemma, gently but firmly persuading mother and daughter to allow Charlotte to be moved into his sanitarium for treatment.

Away from her mother's ruinous control, Charlotte recovers quickly but fears a relapse the instant she's back in her mother's clutches. Lisa and Jaquith suggest an alternative plan: a six-month cruise to South America before returning home. By the time she's aboard ship Charlotte has undergone a shocking outward makeover, her dowdy appearance transformed into something almost glamourous. However, she's still teetering on the edges of mental illness until she makes friends with Deb and Frank McIntyre (Lee Patrick and James Rennie) and their friend, Jeremiah "Jerry" Duvaux Durrance (Paul Henreid).

Jerry's in a loveless marriage, he compelled by his wife to give up a promising career as an architect, and deeply concerned about his youngest daughter, 12-year-old Tina, whose depression mirrors Charlotte's before she was treated. They fall in love but understand the pointlessness of becoming lovers, in the sexual sense.

Minus Jerry, Charlotte finally returns home, dreading the effect her controlling mother still might hold over her. It's here where Now, Voyager really kicks into gear, surprising its audience with its prescient understanding of human psychology and its adultness. This is no manipulative "weepie" at all, really, and instead deeply moving in unexpected ways.

(Spoilers) What's great about the film is how it presents Charlotte as a shell of a woman at the beginning, but how with Dr. Jaquith's help and Jerry's love and understanding she slowly is able to rebuild her life and gradually assert herself out of her selfish mother's control. When the mother dies of a heart attack, right in the middle of an act of defiance by her daughter, Charlotte fears a relapse, but back at the sanitarium she learns Jerry's daughter Tina (Janis Wilson, criminally unbilled) has been placed there, and immediately takes the deeply troubled young girl under her wing, eventually becoming something of a "ghost" mother, a loving and empathetic one Tina never had.

Davis and Wilson, their characters in the throes of deep depression, both express authentic internal desperation. Wilson's Tina is especially hard to watch in her early scenes; it's like watching a child drowning. A scene involving a telephone call is as emotionally powerful as anything classical Hollywood ever did. Both have shut out the world, even those reaching out to help them. Tina is, initially, deeply suspicious of Charlotte's motives, just as Charlotte was of Jaquith's in the opening scenes. Davis, with a dozen years working in front of the camera, knows how to play to the camera lens, wordlessly expressing decades of psychological trauma, while Wilson is a wonder, one of the best child performances ever.

Equally fine are the incredibly tense scenes between Charlotte and her manipulative mother, Gladys Cooper is small and frail yet absolutely tyrannical in her cutting criticisms and thinly-veiled threats. That Charlotte finally gains the confidence and sense of self-worth to stand up to her is a genuinely triumphant moment, as much as Victor Laszlo's defiant singing of "Les Marseilles" in Casablanca. The movie surprises us by then showing how much more Charlotte is capable of, as if she's making up for lost time.

In assuming the mother role to Tina, and maintaining her sexual distance from Jerry, no matter how much they might love one another, it's clear that Charlotte is not making a Stella Dallas-like sacrifice but revels in her new empowerment, helping lost souls as she once was, going to work with Dr. Jaquith and, clearly, donating a large chunk of her inheritance to his good works. She can never have Jerry, and the script admirably doesn't resort to the expected deux ex machina suddenly making Jerry available in the final reel. (Davis, in the aforementioned Cavett interview, imagines that Charlotte would eventually marry Dr. Jaquith instead.) In this sense, Now, Voyager is almost shocking in its progressive portrait of a woman who genuinely takes charge of her life away from those who would own it, and in doing carves a niche that validates her long-lost life.

Video & Audio

Criterion's Blu-ray of Now, Voyager, licensed from Warner Bros., primarily sources the original nitrate camera negative for this flawless 4K transfer, with some bits using a 35mm nitrate fine-grain master. The equally fine uncompressed mono audio sources two nitrate 35mm fine grains. SDH are provided on this region "A" disc.

Extra Features

Supplements include that excellent hour-long Cavett interview, taped the day after Gladys Cooper's death, to whom Davis touchingly pays tribute, as well as her frequent co-star Claude Rains. I think this interview previously appeared on a Shout! Factory collection on DVD, but I found the piece so captivating I ended up re-watching it in its entirety. Also included is a brief but amusing interview with Paul Henreid from 1980, the actor's Austrian accent somehow much thicker than his Warner days four decades earlier; a selected-scene audio commentary by film score authority Jeff Smith and an interview with costume historian Larry McQueen; film critic Farran Smith Nehme delves deeply into the making of the film, while Patricia White contributes the booklet's primary essay. Radio adaptation from 1943 and 1946 round out the extra features.

Parting Thoughts

Now, Voyager is not merely one of those classic Hollywood melodramas often excerpted (always the scene of Henreid lighting up two cigarettes simultaneously, giving one to Davis) but less frequently studied, let alone watched, yet it's a real revelation, its emotional authenticity and attitudes toward psychology years ahead of its time. A DVD Talk Collector Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian currently restoring a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||