| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

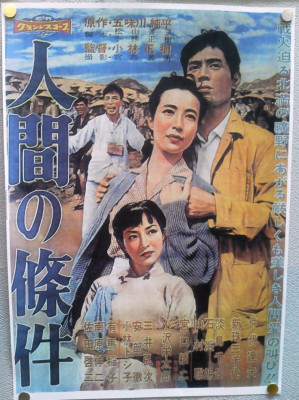

Human Condition (The Criterion Collection), The

Its power undiminished 60 years after it was made, The Human Condition (1959-61) fully retains its power to shock audiences with its unflinchingly honest look at the consequences of Japanese militarism in Manchuria during the Second World War. Based on Junpei Gomikawa's 1958 novel, regrettably never published in English, and directed by Masaki Kobayashi, each of whom witnessed many of the same small humiliations and wartime atrocities as the novel's hero, Kaji, the movie of The Human Condition rebuts a wave of apologist, pro-militarist historical films produced by Shintoho Studios at the time, and Toho Studios' Japanese Navy epics, special effects-driven films that simultaneously glorify and condemn Japan's wartime actions.

The entire story runs nine and two-thirds hours. The first third, known in English as The Human Condition: No Greater Love, was originally released in Japan as two movies paired as a double-feature with separate main titles, while the second two-thirds (Road to Eternity and A Soldier's Prayer) consist of two three-hour-plus movies divided by an intermission break. It's really a six-part epic historical drama, with each part running approximately 100 minutes.

I hadn't seen The Human Condition in 20 years, when my wife and I worked through Image Entertainment's three-DVD set from 1999, which apparently for a number of years was an expensive collector's item. Those DVDs were 4:3 letterboxed, so Criterion's new high-def Blu-rays are a substantial upgrade, A Soldier's Prayer even presented in its original four-track stereo.

Kaji, implicitly a Japanese communist, works for an iron ore mining company in occupied Manchuria. Opposed to the occupation and the Japanese military generally, he obtains an exemption from wartime service by accepting a middle-management post at a remote mining operation, which in turns allows him to marry co-worker Michiko (Michiyo Aratama). Kaji hopes to instill humane working conditions for the mistreated (but still more or less voluntary) Chinese workers. He finds an ally in working stuff Okishima (So Yamamura), but most of the on-site managers are only too happy to beat the Chinese in their charge to meet military quotas.

Soon, with the Japanese forces losing the war, the military demands more ore, assigning half-starved Chinese POWs to the site. Kaji is appalled when they arrived in boxcars like Jews shipped off to concentration camps, many dying en route. Again, against much resistance, Kaji tries to ensure the POWs' safety, but the military police, led by the racist, sadistic Sgt. Watai (Toru Abe) opposes Kaji's "red" methods, while the Chinese prisoners, led by Wang Heng Li (Seiji Miyaguchi, the master swordsman from Seven Samurai), are deeply suspicious of Kaji.

Eventually the military reneges on its deal and conscripts Kaji anyway, where as a new recruit with a leftist reputation, he faces hardships by his superiors and even career enlisted men as cruel and unforgiving as anything back at the mine. Though an able soldier and unusually good marksman, Kaji finds himself incurring their wrath as he tries to help fellow recruits Naruto (Susumu Fujita), 50-something, whose outrage at his treatment boils to the surface; and especially Obara (the late Kunie Tanaka), a hopeless, bespectacled recruit who becomes the target of the career soldiers' wrath. (Obara's story, clearly, was an inspiration for Stanley Kubrick when he made Full Metal Jacket.) As the Soviet Union enters the war and invades Manchuria, the situation becomes increasingly grim.

Watching The Human Condition after so many years, several things about the film stand out. First is the film's frank, unflinching honesty. This is a film no Japanese studio would touch in 2021, so controversial still is its subject matter. A personal anecdote: I was recently shocked to learned that my eighth-grade daughter's teacher lectured his class about the Nanjing Massacre, the 1937-38 rape and murder of as many as 300,000 Chinese by Japanese Imperial troops, claiming none of it ever happened, that it was all "fake news" propagated by the Chinese government. His talk completely contradicted information found in the school's own history books, he was not allowed to make such remarks, but made them anyway, consequences be damned. (And, boy howdy, there were consequences. I made sure of that.)

The point is that, even today, denial of wartime atrocities committed by the Japanese is not uncommon, and it remains a sore point in Japanese-Chinese (and Japan-South Korea) relations even now, with even many prominent government officials fanning the flames, such as regular visits to the controversial Yasukuni (which enshrined Japan's war criminals) by members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which is literally neither liberal nor democratic.

The film was shot extensively on location on the plains of Hokkaido, officially due to the lack of China-Japan relations at the time, though undoubtedly a budgetary consideration in any case. One imagines Chinese audiences, if they ever got the chance to see it, would be both gobsmacked and pleased by the film's historical accuracy. Nevertheless, Kobayashi was probably wise to cast Japanese actors in all the Chinese parts. Though their phonetically-learned Mandarin varies widely, good actors in these parts like Miyaguchi, make this risky move almost seamless.

Another striking thing about The Human Condition is found in its opening titles. Shochiku, skittish about its content, would only co-produce it with partner Ninjin Club, and while populated with Shochiku actors like Keiji Sada (as Kaji's friend from back home) and Ineko Arima (as a Chinese prostitute in love with a POW), the main actors and many of the minor ones came from elsewhere. Nakadai came from the theater and up to that point had worked primarily at Toho; Human Condition was his first leading role. Aratama, a Nikkatsu star, had recently signed a long-term contract with Toho as well. Many others were loaned from other studios or theatrical companies. The roster of big star names like Sada, Arima, Hideko Takamine (in a smallish part as a refugee), and Chikage Awashima (as a conniving Chinese madam) helped ensure its financial success; while emerging talent (some associated with the Japanese New Wave) like Kei Sato (as a soldier) and Kyoko Kishida (as a determined refugee) lend it an artistic legitimacy. And there are even ironic casting choices like Susumu Fujita, the symbol of the heroic Japanese soldier in wartime propaganda films, shrewdly cast here as a way-past-his-prime recruit bullied to the breaking point by the younger career soldiers.

The casual and often sadistic cruelty inflicted by the civilian mine workers, officers and enlisted men on the Chinese, Koreans, and even (and sometimes especially) on its own soldiers and citizens is wrenching in No Greater Love and only gets worse, more excruciating as the film progresses: prisoners are gleefully beheaded (Toru Abe gets my vote as the most vile character in all of Japanese cinema), drown in a tank of urine and feces, starve to death and die of exposure, women are brutally raped. It's so unrelenting the film would be completely unbearable if it weren't so completely truthful and thus difficult to look away, despite the grim subject matter. Having already seen it in its entirely twice before I'd initially planned only to re-watch bits and pieces but ended up seeing it again, all nine-plus hours, over four days.

Video & Audio

Criterion's release of The Human Condition consists of three separate discs, one for each third of the story. The Shochiku GrandScope 2.39:1 image was sourced from 35mm prints taken directly from the original camera negative. The black-and-white images are light years ahead of Image's earlier DVD release. Parts 1-4 are mono but parts 5-6 are in 4.0 stereo, remastered from the original stems. Though dozens of Japanese films had been released in Perspecta Stereophonic Sound going back at least to 1957, this was reportedly the first Japanese production in four-track stereo. The English subtitles are excellent, and Criterion finally seems to be translating more opening titles credits than they used to, a welcome improvement. One last note here: the "resume feature" option doesn't work properly on these discs for some reason. Rather than resuming the film where it left off, for some reason, on my player at least, it tended to resume 30-40 minutes earlier than where it should. Region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

Supplements include excerpts from a 1993 Directors Guild of Japan interview with Kobayashi, conducted by director Masahiro Shinoda; a 2009 interview with Tatsuya Nakadai; a 2009 appreciation by Shinoda; Japanese trailers for all three films; and a good fold-out essay by Philip Kemp.

Parting Thoughts

One of the greatest Japanese films ever made, The Human Condition is a DVD Talk Collectors Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||