| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

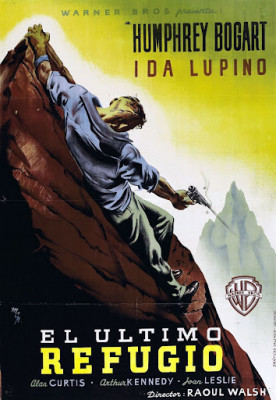

High Sierra (and Colorado Territory) - Criterion Collection

A star-making film for Humphrey Bogart, High Sierra (1941) falls short of the perfection of The Maltese Falcon (also 1941) and Casablanca (1942), but in some respects it was the single most important film of his entire career, and a turning point in the gangster and film noir genres, the ‘40s slate of movies produced at Warner Bros., and on and on. And it's still one helluva good picture; Criterion's new Blu-ray is probably the fifth or sixth time I've seen it and, by golly, it's still powerful, gut-wrenching even.

Far from an overnight success, Bogie had been acting since the early 1920s, making his feature movie debut in 1930. A run of films went nowhere so he returned to the New York stage, creating a sensation as the Dillinger-like Duke Mantee in The Petrified Forest. Star Leslie Howard threatened to walk if Bogie wasn't cast in the 1936 movie version, a reluctant Warner Bros. finally ceding to Howard's after much resistance.

That film was a huge success, but again Bogie's career fell into a rut, he typecast as smooth-talking mugs, smugglers and racketeers to be gunned down again and again by more established stars like Cagney, George Raft, and Edward G. Robinson. Some at Warners, like screenwriter John Huston, recognized Bogie's huge potential as a leading man, but the studio, and even most theater owners and audiences, simply couldn't imagine him as anything other than a heavy.

High Sierra, written by Huston and W.R. Burnett from Burnett's novel, provided a way out. Here Bogie would again play a gangster, a killer, but one with a soft spot, an Achilles heal of humanity often hinted at in earlier gangsters played by others but never so compelling as Bogie is here. His Roy Earle is a character the movie audience deeply sympathizes with; we're rooting for him to pull off this one last job, to grab his share and go back to Indiana and lead the life he's always dreamed about. This sort of character would become a staple in film noir, Sterling Hayden in Huston's The Asphalt Jungle, for instance, but in High Sierra it both transitions out of the gangster genre and into noir in one felled swoop.

Still unable to grasp Bogie's significance (and magnificence) in High Sierra, Warner Bros. famously awarded top-billing to co-star Ida Lupino. She's fine, certainly, but from beginning to end Bogie completely dominates the picture.

Criterion's release of High Sierra is packed with the usual extras. Rather bizarrely though, almost as a footnote in the packaging is mention of an entire second film included in this two-disc set: Colorado Territory (1949), a Western remake of High Sierra starring Joel McCrea and Virginia Mayo that was also directed by Walsh. Past pairings like the two versions of The Lower Depths and The Killers gave both pictures equal billing but here this desirable extra is almost hidden away in the packaging.

Notorious though aging gangster Roy Earle (Bogart) is sprung from prison nine years into his sentence, pardoned through the machinations of his old boss, Big Mac, who needs Roy's experience and expertise for a jewelry heist he's been planning for at ritzy California resort in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Roy is dismayed to find Big Mac (Donald McBride) terminally ill, with crooked ex-cop Jake Kranmer (Barton MacLane) trying to position himself as the new head man. Nevertheless, Roy makes the long, cross-country trip to California.

En route, he becomes friendly with Pa Goodhue (Henry Travers, of It's a Wonderful Life), who is relocating his wife (Elisabeth Risdon) and teenage granddaughter, Velma (Joan Leslie), to California after losing the family farm to creditors. Roy, a backwoods Indiana farm boy himself, identifies warmly with the Goodhues.

At a logging camp in the mountains, Roy meets up with the other men planned for the heist: Red Hattery (Arthur Kennedy) and Babe Kozak (Alan Curtis), both inexperienced, untested but testosterone-heavy gunmen; and Louis Mendoza (Cornel Wilde), the skittish, garrulous "inside man" working at the front desk of the hotel. Roy's annoyed that Babe has picked up a dancehall girl along the way, Marie (Ida Lupino), and insists she be shipped back to Los Angeles where she came from. Quickly, however, Roy realizes she's stronger, more observant, and cautious than the unpredictable Red and Babe, and allows her to stay on.

Anxiously waiting for Mendoza's go-ahead signal over several weeks, Roy visits the Goodhues where he learns that Velma is disabled with a clubbed foot. Consulting with an underworld doctor (Henry Hull) Roy, having fallen in love with Velma, pays for the corrective surgery her family cannot afford. She's grateful, but already engaged to a man back east.

Though Roy gets away with the jewels, every other aspect of the heist goes wrong, and he and Marie become the subject of a nationwide manhunt.

High Sierra's screenplay counters Roy's criminal behavior with obvious but effective sentiment, laying it on real thick. Not only does Roy fall in love with a "cripple" he's determined to cure, but Roy adopts a devoted dog, Pard, homeless since the death of its owner in a landslide. The dog determinedly follows him everywhere, even riding along for the heist. Bogie's fine acting never allows Roy's relationship with Marie or the dog to become maudlin, however. Indeed, it's impossible for audiences not to eat it up.

Though a modest "A" costing just $491,000, the film is packed with good actors, including Jerome Cowan (future Miles Archer in The Maltese Falcon) as a reporter near the end, Eddie Acuff as a bus driver, and Willie Best as Algernon, offering comedy relief that's pretty painful seen today. (Best was the poor man's Stepin Fetchit, a genuinely funny actor, though Best was quite good in The Ghost Breakers with Bob Hope the year before.)

High Sierra neatly straddles the worlds of the Warner Bros gangster picture, by this time a source of nostalgia as much as anything by 1940, and the burgeoning if murkily-defined world of film noir. In High Sierra Roy Earle is an anachronism, the last of the old-time gangsters marked for death for years and years, an inevitable violent death put delayed almost Rip Van Winkle-style by a long prison sentence. With his pronounced graying temples, Roy is world-weary, wishing it were possible to return to the innocent farm boy universe of his youth. Disinterested in fast dames and high living, he doesn't know what he wants, except to walk in green grass among the tall trees, simple pleasures denied him behind high prison walls.

Walsh's Colorado Territory is inferior to High Sierra but still above average on its own terms. What's peculiar about the film, which credits neither Burnett nor Huston at all, is that some scenes recycle dialogue almost word-for-word while radically changing other aspects of the original story, and not just to accommodate the Western setting. Joel McCrea plays Bogie's part, with Virginia Mayo and Dorothy Malone in those essayed by Lupino and Leslie, respectively. Henry Hull appears in both films playing different parts, here assuming the role originally played by Henry Travers.

The most striking changes are the complete absence of the dog and the young girl's clubbed foot. In the remake, Fred Winslow (Hull) has been swindled into buying sight-unseen a worthless ranch, prompting outlaw Wes McQueen (McCrea) to give him money to dig a well, hardly as compelling as making a lame girl walk again. Winslow's daughter, Julie Ann (Malone) is no innocent here; more like a noir femme fatale, she plots to steal the stolen money for herself or turn McQueen in for the reward. In a clumsy but interesting addition, McQueen's attraction to Julie Ann is not prompted by any innocence she projects, but rather because, unconscious to McQueen, she resembles the fiancée he loved but who died while he was in prison.

A few other changes moderately improve upon High Sierra. In Colorado Territory, the two young gunmen, here played by John Archer and dancer James Mitchell, conspire with the ex-cop, here an ex-Pinkerton man, to kill McQueen immediately after the daring train robbery. The posse after McQueen are equally reprehensible, ready to deceive and even whip the Virginia Mayo character to flush out the elusive bandit.

The filmmakers almost softened McQueen further, probably at McCrea's insistence; unlike Bogart circa early 1941, McCrea was an established star, and had been one for two decades. After working in myriad genres, beginning in 1946 McCrea starred exclusively in Westerns. Many of these later films were excellent, but whether McCrea was playing a hero or an outlaw his screen persona, one of peerless basic decency, was always part of the package. This familiar persona works to his advantage as McQueen, for McCrea, a greatly undervalued actor, couldn't help but exude sincerity and earnestness.

Mayo, on the other hand, fights an uphill battle, the fair-skinned blonde playing a darkish-skinned part-Indian dressed like a waitress as a cheesy Tex-Mex restaurant. Malone fairs much better. Hull is surprisingly good considering Travers was a far subtler actor than hammy Hull, rarely anything less than broadly theatrical. But his folksy southerner farmer builds interestingly, especially when appalled by his conniving daughter's greed.

Video & Audio

Criterion presents High Sierra in a nigh perfect 4K restoration all the more amazing as it was culled from a 35mm nitrate finegrain master positive (rather than the original neg) of the original 100-minute release version (a shorter reissue cut, running 95 minutes, has also circulated through the years; some footage from that shorter finegrain was also used). Nevertheless, the black-and-white, 1.37:1 standard image is very impressive throughout. Colorado Territory is preceded by a title card warning viewers that this is an "unrestored scan...from the 35mm original camera negative...housed at the Library of Congress. Visible damage, jump cuts, black frames, and dirt remain." I expected something resembling dog meat yet the presentation plays just fine, with some speckling, yes, and a few black frames and other minor damage, but overall it looked terrific. I felt like I was watching a good 35mm print in a theater; very film-like. The mono audio is fine, optional English subtitles are available, and the discs are region "A" encoded.

Extra Features

Besides Colorado Territory (see above), the many supplements include: a new conversation about Walsh with film programmer Dave Kehr and critic Farran Smith Nehme; The True Adventures of Raoul Walsh, a 2019 documentary; Curtains for Roy Earle, a TCM-type featurette; Bogart: Here's Looking at You, Kid, a 1999 episode of the British series The South Bank Show; a new video essay incorporating footage from a 1976 AFI interview with Burnett; a 1944 radio adaptation; a trailer; and a booklet essay by Imogen Sara Smith.

Finally, there's a new interview with media historian Miriam J. Petty about actor Willie Best. It's very interesting, informative, and perspective, but also plays like Criterion trying to head off criticism from liberals insisting 80- and 90-year-old movies conform to 2021 standards and politically-correct "enlightenment." It's overkill, considering Best is onscreen maybe five or six of the film's 100-minute running time, playing a type of racial stereotype that turns up in literally hundreds of movies from the 1930s and ‘40s. It's a valuable extra, but I hope this isn't the start of a trend, disclaimer-type supplements video labels will feel obliged to include because they have to.

Parting Thoughts

Two films for the price of one: a classic of two genres and a strong if imperfect Western, backed by scads of extra features and fine HD transfers, High Sierra is a DVD Talk Collectors Series title.

Stuart Galbraith IV is the Kyoto-based film historian largely absent from reviewing these days while he restores a 200-year-old Japanese farmhouse.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||