| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Onibaba

|

||||

The few Japanese ghost story movies distributed in the U.S. almost became legendary in the 1960s. Among horror fans, not everyone had seen Kwaidan or Onibaba or Face of Another (not exactly a ghost story) but those who did tended to rave about them. Kaneto Shindo's Onibaba got fairly good play stateside with an ad campaign that would attract any horror fan. Criterion brings it to DVD in a fine presentation with some extras we don't expect to see on a 40 year-old Japanese film. The only thing it can't reproduce is the effect of the theatrical experience, the focus of attention in a movie theater that rewards a subtle reading of the film.

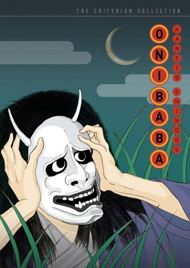

Before the 70s "objective revolution" the best horror films were often strangely beautiful. Val Lewton films were elegant and civilized but overall the genre's inability to directly depict death and mutilation resulted in writers and directors finding subtle ways to communicate dread, the same way that the makers of romantic comedies had inferred sex while remaining technically chaste. Even Hammer films had some degree of suggestion, often substituting bright color stylization for explicit depictions of morbid subject matter. The height of aestheticism came with the European horror boom of the 60s, where a funeral atmosphere could become delirious (The Horrible Dr. Hichcock), sex and death could be fused in a single image of Barbara Steele (Black Sunday) and a gothic curse could merge with modernistic surgical nightmares (Eyes without a Face). These pictures conjure beautiful nightmares, as opposed to mechanical shocks. Onibaba stems from a traditional Japanese horror story about a haunted "mask of flesh." The basic idea is old-fashioned but effective, and I've seen it used before and since. One old Twilight Zone episode had a group of corrupt heirs donning ugly masks to humor their benefactor during Mardi Gras. Naturally, the masks reflect their true selves. When it it's time to take them off, everyone has a surprise coming. The supernatural part of Onibaba is secondary to director Shindo's main theme - the human debasement of war. The two women make a ghoulish living in isolation, with survival their only remaining value. It's a harsh world where everyone must make do on their own. They simply invert the expected situation - two women alone would more likely be the victims of soldiers fleeing the wars. The natural environment is everything in this picture. Their habitat is tall marsh grass that waves with every breeze, and we rarely see over it. The women labor at their criminal business under the sun and by moonlight, wolfingd down food when they can get it and collapsing afterwards in exhaustion. Mother and daughter-in-law have a crooked bond that breaks with the return of the equally amoral Hachi. The women had planned for their rotten lifestyle to end with the return of their man. When they find out he's dead, all bets are off. The young widow gravitates toward Hachi out of sheer sexual desperation. He runs around in a frenzy for want of a woman, and even the mother goes slightly nuts for being shut out of all the sex. With their lives completely overrun by the base instincts of survival and sex, Onibaba is a grim microcosm of the human condition. Kaneto Shindo's beautiful B&W scope images integrate the horror content with ease. The most frightening thing in the film is the black pit in the ground where the women throw the bodies of their victims. It waits calmly, like a doorway to hell. The mother has to descend into the pit to carry out her plan. Without getting into details, there's this grotesque demon-mask that she "borrows" in an attempt to control her daughter-in-law. It's pictured in a drawing on the DVD cover but in the film has a strange life of its own - in the shadows of their hut, or looming like a banshee in the midnight marsh grass. In the theater there were moments of real terror that might not be easy to replicate in the distracting home theater setting. With an audience waiting as one to find out what happens next, Onibaba was riveting. There's an abrupt ending that lacks the tidy closure we expect from genre pictures. It might be a slight disappointment, like the vague conclusions of some of the tales in the more stylized Kwaidan. Criterion's DVD of Onibaba is a stunner, starting with its superior transfer. In the enhanced scope (Tohoscope?) rendering the perpetually waving sea of grass never breaks up into digital mush. The image detail and density are fine - in the darker images we never feel that we're seeing too much or too little. Director Shindo is on camera in a recent interview. He's over 90 but looks as if he could direct another film tomorrow. The fat inset booklet contains a statement from him as well as a good essay by critic Chuck Stephens and a translation of the cryptic Buddist fable that served as the story source. The best extra is a lengthy home movie shot during production by Kei Sato, the actor who plays Hachi. It's the kind of thing we wish would surface for our favorite films. We see the crew establishing a primitive camp out in the grass fields and living together as a unit. They look like hardworking artisans with a communal goal. Even with the deprivations of life in the wild they must have been a group of happy campers creating something they could be proud of. Production notes and a stills gallery explain the particular problems of filming. The unstable ground was so saturated by water that the hellish pit had to be cheated, and its interior constructed as an above-ground set.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Onibaba rates:

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |