| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

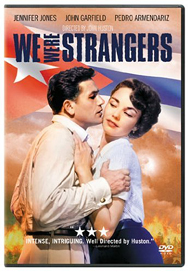

We Were Strangers

|

||||

John Huston never made an uninteresting movie, and the overlooked We Were Strangers is one of the best of his more obscure titles. It deals with revolution almost as directly as does The Battle of Algiers and is fascinating from a political point of view. The heroes are trying to bring down a corrupt government in Cuba, and the romance between movie stars Jennifer Jones and John Garfield is minimized in favor of an investigation of what it takes to fight the system. By modern standards they're both terrorists and Huston and Peter Viertel's incisive script lays out the harsh rules of modern political struggle without flinching. Once a person is willing to lay down their life for a cause, all normal rules are suspended. The story even addresses the idea of one of the rebels becoming a suicide bomber.

We Were Strangers is as good as Hollywood could make a film about Latin American reality in 1949. Everyone speaks English and an inordinate amount of rear projection is used to place the movie stars in the distant locations. But the script has a knowing knack with local detail, and the Havana we see is the real thing and not a studio set. Unlike thrillers that just happen to take place during a revolution, We Were Strangers is mainly about violent resistance to an abusive government. It's about ideas first and not entertainment and thus didn't get a lot of critical attention when new. Richard Brooks had a hit with a vaguely similar film in the next year's Crisis, but it is definitely an escapist thriller. American doctor Cary Grant is forced to care for a deranged Latin American dictator, with no real political content beyond Handsome American = Good, Psychotic Latin despot = Bad. 1949 America still thought of revolution in the fantasy terms of The Adventures of Robin Hood and wasn't ready for the disturbing notion of heroes that hide out from the law while plotting abominable crimes. The movie is more like Edgar Allan Poe than anything else, and the leading characters' commitment to violence has a strong element of a Death Wish. The outspoken script has a complex response to the meaning of becoming an underground revolutionary fighter. The "strangers" in the story refers to the unavoidable alienation felt by the small group of patriots who join to dig the tunnel. Skulking behind drawn curtains, smeared with red mud and their faces covered by dust masks, their only hold on reality is the certainty of their cause - and even that falters. China is committed to killing the grossly aggressive Ariete and stays on course, but one of the diggers loses his mind and wanders into the streets trying to confess his crime to any passserby that will listen. Dockworker Guillermo (Gilbert Roland) invents a folk song about Tony Fenner, the American who came to fight with them. He's the one that at one point suggests putting explosives in a truck and driving it into police headquarters as a suicide bomb. China ends up being the weak link in the operation. When the secret policeman Ariete 1 becomes personally interested in her the group's work becomes more difficult. However, the hope that he might sleep with China is probably what keeps Ariete from closing in on the conspirators more quickly than he does. Much of the film's dialogue centers on the authors' thoughts about desperate political violence. New Yorker Tony is the one who suggests a Death Wish. He logically explains that only by being willing to give one's life to a cause does one gain the moral right to take a life. When it looks as though their plan will fail, Tony feels honor-bound to die as a gesture of commitment to the poor people of Spanish Harlem who raised the $12,000 to send him to Havana. The movie posits America as a fabled land of peace and plenty and the source of idealists like Tony who will come to fight for justice in other lands. Even though it's eventually revealed that Tony has a personal stake almost as strong as China's, the movie absolves America of any involvement in the repressive Cuban dictatorship of Gerardo Machado. Just as with Battista twenty years later, American business interests - operating alongside organized crime - conspired with the government to loot the country; in both periods Havana was considered a brothel for rich Americans looking for gambling and vice. The corruption was begun by Prohibition and tempered somewhat by tight money in the Great Depression. The torture chambers and extra-legal executions under Machado and Battista were medieval atrocities - China's resistance leader (played by ex-matinee idol Ramon Novarro) refers at one point to political prisoners being fed to the sharks in Havana Bay. The only official American presence in the film is the powerless Yankee president of the bank where China works (Morris Ankrum). He has little choice but to inform the police when China taps into Tony Fenner's bank account. We Were Strangers ends in a frantic, slightly existential machine gun battle that plays as a precursor to bloody last stands in later violent epics like The Wild Bunch. Trapped in a tiny house, lovers China and Tony strike back with a Tommy Gun and dynamite. Jennifer Jones had already fought with Winchester rifles in Duel in the Sun and looks surprisingly adept blasting away at the police, with her crucifix prominent in closeups. 2 I can't help but feel that this is how self-deluded outlaws like The Weather Underground and the Symbionese Liberation Party saw themselves, as noble freedom fighters out of a Jefferson Airplane ballad. China and Tony are romanticized even as Strangers undercuts their bravery with cruel ironies that make any personal gain from their rebellion seem hopeless. The last words in the movie strike its only false note by paraphrasing Tom Joad's Joe Hill-type "I'll be there" speech from The Grapes of Wrath. Almost everything else in the movie is eye-openingly original. Unless I've lost my marbles, one brief shot through the wire mesh of a bank's in a security cage shows the clerk inside to be played by John Huston. After this movie and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre Huston apparently shook the habit of making cameo appearances, at least for a few years. Columbia's DVD of We Were Strangers is an excellent encoding of a good element that shows wear only at the ends of reels. The image is sharp and detailed and the abundant rear projection scenes look good. Doubles are used in many exteriors, such as the impressive gun-down on the University steps. We at UCLA were impressed by the scene; Ronald Reagan's police merely clubbed some people and broke the arm of a professor that resisted arrest during our 1971 Cambodia-Laos 'unpleasantness.' There are no extras except for some promo trailers. Columbia's great-looking cover art shows Garfield and Jones before a Cuban flag, in a romantic clinch atypical of the movie.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

We Were Strangers rates:

Footnotes:

1. The policemen in the

movie are called porras or porristas. My wife vaguely identified the term as a curse

word but didn't know more about it than that.

2. Tony's Thompson machine gun has an anachronistic straight magazine

that was introduced during WW2; in 1933 the gun carried the round magazine familiar from gangster movies

(the gangsters surely brought them to Cuba on rum-running boats). I learned this on the film

1941. One reason for the change is that the old magazines had to be carefully loaded and

were prone to jam; our altered prop guns jammed frequently.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |