| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Brainiac: |

|

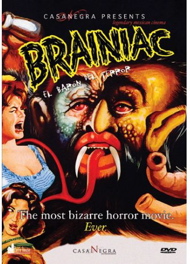

Brainiac: El Barón del Terror CasaNegra 1962 / B&W / 1:37 flat full frame / 77 min. / El Barón del terror / Street Date August 29, 2006 / 19.95 Starring Abel Salazar, Rubén Rojo, Rosa María Gallardo, Germán Robles, René Cardona Cinematography José Ortiz Ramos Production Design Javier Torres Torija Film Editor Alfredo Rosas Priego Original Music Gustavo César Carrión Written by Federico Curiel, Antonio Orellana, Alfredo Lopez Portillo Produced by Abel Salazar Directed by Chano Urueta |

Most of us fourth graders had heard of Brainiac long before we actually saw it; it enjoyed a special playground notoriety as something to be whispered about in a few short statements -- "You should see this guy's tongue!" "And he takes a bite from a plate of brains!" The film clearly came from a galaxy unrelated to our beloved Universal monsters. If Savant was an expert on the subject, it was due to the fact that I had read a Famous Monsters article on "Mexi-horrors" and had bugged my Spanish teacher to help translate the intriguing titles, although no help was needed with El Barón del terror.

Chopped up and re-dubbed by K. Gordon Murray, Brainiac is a favorite of cult enthusiasts seeking outrageous thrills with no redemptive social content whatsoever. CasaNegra presents this cheapjack monsterpiece from Mexico City in an amazingly pristine original cut, with every juicy slurp intact.

Brainiac is delirious, sordid monster fun for 'undiscriminating audiences.' Its only practical function is to be able to say "I saw The Brainiac last night," just to see which of your friends wants to hear more and which suddenly hurry away whenever you approach. Then again, it's no trashier than any number of gory and cheap American movies of the 1950s, even some bearing studio logos. Columbia's Creature With the Atom Brain comes to mind. That picture about reanimated corpses with radioactive noggins can be described as "cheerfully worthless." So why do we enjoy them so much?

This potboiler plays out in nearly bare sets, like a Sam Katzman quickie. The main targets of the Mexican Spanish Inquisition were Jews, but unless the catchall charge of Heresy applies, Baron Vitelius is condemned for everything in the book except being Jewish. He's 100% guilty of diabolical wizardry, as proven when he transfers his chains to the ankles of his jailors. Vitelius goes to his doom laughing at his executioners. Brainiac thusly shows its politics by inferring that the bloody Inquisition was justified and moral.

1961 sees Vitelius' rebirth in the form of an uniquely absurd monster. The cyclical return of a rogue comet is worked into the story via some pitiful special effects involving sparklers held in front of star-field backgrounds. We can see paper folds in one telescopic view of the moon. Vitelius returns via a meteor and some cheap dissolves. He's capable of transforming at will between handsome and horrible. The suave Vitelius knows all about the 20th century. He immediately receives upper class visitors in a castle that, like so many details in the movie, comes from nowhere. The horrible Vitelius (let's just be informal and call him Brainiac) is an ugly monster with a head as big as a Mardi Gras mask. It's hairy, bald and has a horrible long nose; the whole thing looks uncomfortably like a hateful Jewish stereotype as a bogeyman. Brainiac gleefully sucks brains, making loud slurping sounds. He also delights in hypnotizing a husband, and then forcing the man to watch the molestation and brain-draining of his beautiful wife. Another wife screams for her husband, to find that Brainiac has drowned him in a bathtub by hanging him by his heels. Some of this plays as funny, but the film never hints at self-parody.

This Brainiac guy has a real cerebellum on his back. In the uncut Mexican version he victimizes a streetwalker with no connection to his vendetta. When masquerading as the genteel Vitelius, he takes little brain breaks, strolling over to a locked trunk to sample some custard-like cranial leftovers (?) tucked away for snacks. Perhaps Brainiac can tell which victims have solid, thinking brains and which have skulls full of yummy tapioca.

The film's crude storytelling flatters the least sophisticated viewer. Vitelius transforms through clumsy dissolves, a device also used to identify his prey. One after another, 1961's victims dissolve to reveal the similar faces of the 1661 executioners. This part of the movie is just ridiculous, as even female descendants still bear the same family name. After 300 years Vitelius would need a genealogist to identify the presumed hundreds and hundreds of offspring of his six or eight original Inquisitors. And are we to believe that none of the inquisitors were priests, who technically should not have had any offspring at all?

Viewers undeterred by those considerations will be floored by Urueta's use of tacky, overly bright rear-projected stills to represent all exteriors not shot on interior sets. Like the best of American Z-filmmaking, Brainiac seems to take place in some unused broom closet of the imagination. When the cops finally corner Brainiac, they stride into a private residence with a pair of flamethrowers, ready to put Vitelius to the torch!

Genre aficionados will copycat-connect Brainiac's immolation with Ron Randell's fiery fate at the conclusion of Allan Dwan's The Most Dangerous Man Alive, released in 1961 but filmed in Mexico a couple of years before. The monster's brain sucking habit is on a par with the precociously gruesome flying brains in Fiend Without a Face, and the idea of a horror being triggered by the reappearance of a comet hails from the Italian-filmed but Mexican-set Caltiki, the Immortal Monster. Brainiac's bulbous, inflating rubber head has no precursor outside of nightmares.

Producer and star Abel Salazar created a number of popular Mexican horror films, mostly with supernatural themes. Director Chano Urueta (The Witch's Mirror) is credited with initiating the 'surgical horror' subgenre in 1953 with El monstruo resucitado. Apparently a member of a nucleus of industry insiders, Urueta is one of four Mexican directors that hogged major speaking roles in Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch: He's the white-haired village chieftain who says, "In Mexico Señor, these are the years of sadness." I guess those sad times followed directly after the happy years of eating brains out of a serving-dish!

CasaNegra's DVD of Brainiac is a beauty, with a perfectly preserved image. We only wish that the transfer had been 16:9 enhanced to make the picture sharper; it gets much softer when blown up to crop away the vast empty space below the action. The show can be heard with the original Spanish, or the K. Gordon Murray re-dub audio soundtrack (which has some synch issues, according to web reports). Subtitles are removable. Savant's screener displays some odd video breakup in the final scene, a vertical banding on the left extreme of the frame.

After such a commendable transfer, some of the disc extras lean toward a campy comedy mindset. A credited "Kirb Pheeler" (such wit) provides the commentary and an 'Interactive Digital Press Kit" that consists of nothing more than excerpted scenes and sub-MSTK3000 jokes. The commentary is an okay listen for casual monster fans looking for fun. Kirb has read the same articles we read and he recites familiar facts about K. Gordon Murray, but the curious fan is not likely to learn much. 'Pheeler' rightly names text bio writer David Wilt as an encyclopedia on the subject of Mexican horror, making us wonder why we can't hear Wilt pontificate instead. Perhaps I haven't read the right sources, but I've always wanted further explanations why Mexican horror films were allowed to be so gory and oversexed, and yet are so conservative at heart. Surely a trashy picture like El Barón del terror wasn't intended for upscale theaters in Mexico City.

Also, Phil Hardy's Encyclopedia of Horror Movies tells us that Mexican film producers required government approval to operate; some companies were licensed only for short films and circumvented that restriction by making serial episodes that could be re-edited into features. The prolific Mexican film industry appears to have been a tightly controlled racket dominated by big time names like Emilio Fernández. How does that compare to the film industries in Japan or England, where the same 100 actors also seemed to monopolize all of the available work? Or do foreigners perceive the American film industry as operating the same way? Brainiac may be a campy cult classic, but these Mexi-horror films provide a commercial bridge between art-house cinema (La Perla) and the ultra-trash thrillers that show up frequently on Spanish language cable stations. Although we applaud CasaNegra's superior video quality, we would have welcomed an opportunity to learn more.

Similar attitudes carry over to the Spanish language input. An okay text overview of Mexican horror films is credited to one "Casamiro Buenavista," who could be a real person, but is more likely another pun. Casimiro is a real Spanish name; when spelled that way, "Casimiro Buenavista" translates as "I almost see a nice view." Are our legs being pulled in Spanish, now? ¡Qué chistoso, hombre! No nos llame a nosotros, nosotros lo llamaremos a usted."

Menus and packaging artwork are, as usual for CasaNegra, beautiful. The disgusting but irresistible original poster provides the basis for the cover art. It turns up displayed on a garish theater marquee in Barbara Loden's Wanda from 1970.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Brainiac: El Barón del Terror rates:

Movie: Good (?)

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Essay: By Casamiro Buenavista; Brainiac "Interactive" Press Kit; Commentary by Kirb Pheeler, Radio Spot; Loteria Game Card; Cast and Crew Biographies; Poster & Stills Gallery

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: September 14, 2006

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |