| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

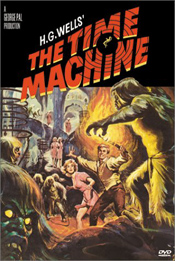

The Time Machine |

|

The Time Machine Warner Home Video 1960 / Color / 1:78 anamorphic 16:9 / Dolby Digital 5.1 / Street Date October 3, 2000 / 19.98 Starring Rod Taylor, Yvette Mimieux, Alan Young, Whit Bissell, Sebastian Cabot, Tom Helmore Cinematography Paul C. Vogel Art Direction George W. Davis, William Ferrari Film Editor George Tomasini Original Music Russell Garcia Writing credits David Duncan Produced and Directed by George Pal |

Warner Home video is pretty stingy with their library output, but when they do bring out an older

title, even a genre movie like The Time Machine, they do a first class job. Actually, George

Pal's 1960 version of the H.G. Wells classic is as about as close to mainstream as a genre piece

can be. Like

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and

Journey to the Center of the Earth,

this was conceived and

budgeted as an A-class family attraction from the get-go, in the hopes that Wells' name would

pull in the same crowds as did Jules Verne.

Synopsis:

1899. George Wells (Rod Taylor) invents a time machine and demonstrates it to his stuffy friends, hoping to interest them in the idea that an awareness of the future will inspire men to redirect their energies away from war profiteering. Disillusioned by their inability to see beyond petty comforts, the pacifistic George bids his friends farewell and ventures into the future. Everything he sees is warped by war. His best friend Filby (Alan Young) dies in WW1. Finally, a war with nuclear satellites in 1966 effectively ends civilization.

When George stops in 802,701, Earth seems to have become a Garden of Eden. He discovers a strange society of beautiful but passive people called Eloi who never grow old. Disenchantment sets in when he finds that the Eloi have lost all knowledge of independence, curiosity, and chivalry. But he meets the comely Weena (Yvette Mimieux) and eventually discovers that this Eden is actually a human stockyard; the Eloi are pampered and husbanded as a food supply for the subterranean Morlocks, a race of hairy green monsters with glowing eyes and snaggle teeth. Seeking to inspire men of his own time, George instead becomes a warrior-emancipator in this remote future world.

The Time Machine is easily George Pal's best directed movie, and goes nose-and-nose with The War of the Worlds as his best film overall. It was a solid hit in 1960; an ecstatic Savant sat through it twice. Standing alongside the popularity, however, were the misgivings of sober critics who decried Pal's diluting of Wells' original story. In 1895, the Darwinian idea that Capital and labor might devolve into separate species of men was intellectually controversial, and Wells had used it as a political critique of his times.

Keeping Wells' framing device of the two 1899 dinner parties almost intact, Pal and screenwriter David Duncan greatly altered the Eloi of the 802nd Millennium. Wells' Eloi were a depressing race of slight and effete midgets who resembled miniature deer on two legs. When trying to communicate with them, the original Time Traveler (he had no given name in the book) had zero luck getting beyond 'hello' and as such his adventure was more like a nightmare than a journey to a faulty Eden. The events in the book are also more depressing. The Time Traveler has a soft spot for Weena, but as she's only quasi-human, the romantic angle is lacking. In fact, Wells' Time Traveler is less an emancipator (although he mulls over this idea) than a typical English traveller in a Third World land, shocked by everything he sees and having a tough time coping with anything un-English. This for a man supposedly disenchanted with every aspect of his own time.

Unlike screenwriter Duncan's revolutionary hero, Wells' thoughtful time tripper finds no great moral lessons, just a despairing future he cannot alter. When you watch the film's use of matches and fire to re-ignite the spark of basic civilized values, remember that in the book, the only thing the Time Traveler succeeds in doing with his lucifers is accidentally burning down the forest, and a lot of Morlocks and Eloi with it.

Taken by itself, most of The Time Machine is dead on the mark, entertainment-wise. Pal sketches 1899 well and his actors are far less affected than usual, probably because they too were enchanted with the material. The under-appreciated Rod Taylor (who had played in an almost identically plotted movie, World Without End, four years earlier) shows considerable charisma. Yvette Mimieux is perfectly fragile and heart-melting, an effect that still worked its charm on Savant 12 years later when he served her popcorn at the National in Westwood, and gushed as only a fan-boy can. Alan Young is solid as Pal's moral anchor, affecting an endearing Scots accent.

Pal did a good job matching the appropriate effects to his story, given the lowly status of effects at the time. In 1960 only big studios had the time and money to be creative, and usually preferred the control factor of keeping the work on the lot. Pal had been burned this way before, when Paramount got cheap on him and made him accept unfinished or unrefined shots. MGM probably realized Pal could wangle an outside vendor more cheaply and come up with a better product anyway.

The Docu.

The 50 minute TV documentary, The Time Machine: The Journey Back included on the DVD gives an indication of Hollywood decades before special effects took over. The docu tells the tale of The Time Machine's title prop from construction, to auction, to its rediscovery in a thrift store and reconstruction by some dedicated effects people (Tom Scherman, hooray!). The haste and bluntness of the effects process can be judged by the fact that as soon as the throne-like Time Machine prop had finished shooting, it was sawed apart to film inserts of its control panel. Nowadays there'd be three sturdy props with breakaway variations; the original Time Machine was a delicate construction that barely lasted through shooting. Nice that it doesn't look it.

The docu features the ubiquitous monstermaker and prop collector Bob Burns, but also details other effects processes. At one point Gene Warren talks about a talented painter whose canvasses were animated as he painted them, to produce images of foliage growing and such. If I'm not mistaken, the shot of leaves and apples growing during this explanation is really replacement animation of Pal's familiar Puppetoon variety. Later on the docu shows views of entire landscapes changing with the seasons, and an Eloi dome being built, which Savant thinks correctly illustrates the painter's work.

The docu has a newly acted scene between Alan Young and Rod Taylor reprising their characters that starts well but doesn't add up to much, except making us wonder why sequels to The Time Machine were never made. With all the principal actors alive and kicking, it would seem a natural, especially in the early 70s when Pal was in a slump and Fox was mining annual pay dirt with its Planet of the Apes series. Pal apparently floated a number of scripts, but nothing ever came about. One reason for this might have been the notion that shows like the Ape series and television's The Time Tunnel had left Pal's simple go there - come back plotting far behind. Science Fiction readers, especially those hip to the mind-warping puzzle tales of (the great, wonderful) Phillip K. Dick books like Ubik and The Man in the High Castle also probably felt that Wells' original story was a great concept that time had made obsolete. It remained for Zemeckis and Gale's clever Back to the Future movies to rediscover and mine the time travel concept for general audiences.

A literary discovery?

Savant wants to explain a revelation he had while reading an uncut copy of The Time Machine in 1979. I've read several books on Wells since then, and have scoured the web, and have yet seen a mention of this, so forgive me if I mistakenly think I've discovered something here.

The Time Machine is supposed to be pretty simple stuff, the book that introduced readers to an abstract concept later brought to a higher level of complexity, it is usually assumed, by other authors. Everyone is aware of time travel conundrums, like the question, "If you go back in time and kill your other self, will you disappear, because then you can't have lived into the future to go back in time?" This has pretty much replaced the great chicken-egg debate as the classic schoolyard argument-starter.

Filby (the book's narrator), presumes that the Time Traveler met some calamity in the past or the future, because he never returns to 1900, and the story ends in a bitter question mark. Pal and Duncan softened the sadness with the 'which three books' gimmick, which works well. But, although Filby didn't realize it, in the book the Time Traveler did return.

The Silent Man.

The guests are all identified at the first dinner party. At the second, Filby makes brief note of a guest identified only as The Silent Man. This man, a bearded, older fellow, is assumed to be someone else's tag-along guest, but Filby does not know whose. The Silent Man (pointedly capitalized each time he is mentioned) takes no part in the heated discussions, and simply observes what happens. The only thing he does is stare at The Time Traveler, and pour him a glass of wine. He never says a word. When the dinner party breaks up, The Silent Man slips away, the perfect party crasher.

The Silent Man is obviously the Time Traveler himself, returned at an advanced age. Older but perhaps wiser, he's there just to contemplate his younger self. His motive has to be guessed at, and it is easy to read into his blankness anything one wants. Perhaps the Time Traveler had many adventures, and before dying wanted to reflect on his origins. Maybe he's been a tourist throughout the ages, taking pains to be a fly on the wall at all times. After his soul-crushing trip to the twilight of existence, the future with the empty beach and the giant crabs, perhaps he finds comfort just being an anonymous man among other men.

Is Savant totally fooling himself in thinking this is something new to report? It alters his impression of the conclusion 180 degrees, and forces a reevaluation of Wells. He now seems to have been perfectly capable of conceiving of Phillip K. Dick time puzzles, even back in 1895. Perhaps Wells thought his Victorian audience wasn't ready for such complications.

That's the Savant literature lesson for the day - The Time Machine has subtleties for which Wells was rarely given credit. If you make a lunge for the book to check this out, be forewarned that some copies have it, and some don't. The original book had several lives, serialized in periodicals and under separate cover; The Silent Man may have been edited out for later versions. For all Savant knows, he may have been an unauthorized addition by a 'creative' editor in a subsequent printing - like the confusion of Captain Nemo as 'Count Dakkar' in differing editions of 20,000 Leagues.

Turner/Warner's DVD of The Time Machine is a beauty, even better than the earlier MGM stereo laser disc that revitalized the film beyond the cropped and crude television transfers that had been seen for 30 years. The DVD looks great in 16:9 enhancement, and a lot of the mattes and opticals that looked murky or mismatched on the laser are improved. A few scenes are a bit bright, but the overall impression is of a perfectly restored DVD version of what is a lot of fans' favorite movie. If you've never heard the stereophonic track, the expressive Russell Garcia score is a very active and dynamic surprise. The packaging claims a separate music track that's not there. Along with the docu the disc offers a very good original trailer, and some text bios of the stars and producer.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor, The Time Machine rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: TV docu, trailer, production notes

Packaging: Snapper case

Reviewed: October 2, 2000

|

More H.G. Wells scrutiny! See Savant's article on the uncut version of Wells' personal production,

The Things that Came Out of THINGS TO COME. |

Text © Copyright 2000 Glenn Erickson

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |