|

|

Foreign Intervention

and the

American Western

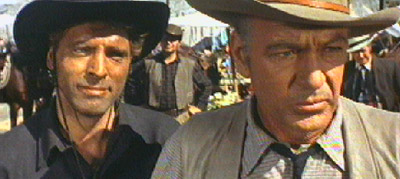

Faded snaps from the Savant archive: Claudia and Burt

The new DVD of The Professionals and the 'Mexican Adventure' Western Subgenre.

Part One.

The first part of this week's installment is practically an ad for Columbia TriStar DVD. Savant just wants to

express his delight at how at least one studio is husbanding its film and video library

Columbia/TriStar's terrific new 1999 DVD of Richard Brooks' 1966 big-budget Western

The Professionals is just

another example of the superb quality of DVD work that continues to come out of that studio. In contrast

to the tentative and budget-conscious attitudes of the other majors, Columbia TriStar would seem to be throwing

money at its Columbia library of films with both fists. What appears on DVD is but the tip of an iceberg:

when movies as humble as Creature With the Atom Brain are being remastered, looking far better than

it ever did in 1955 double-bill grind houses, then you know they're not being stingy with the budget.

Elsewhere, 'library' titles are treated as a second tier to be given quality treatment only if their

market value promises immediate profit. Note how every Stanley Kubrick film on the map suddenly

jumped to 'hot' status upon his death: can anyone tell me that Killers Kiss would go

to the head of the line if there hadn't been a timely Kubrick tie-in? If Atom Brain were the

property of another studio, it would probably be ignored and forgotten, along with a lot more 'marketable'

films.

A casual walk down the halls of the Columbia TriStar vault reveals stacks of new D1 feature masters,

even for titles that barely get shown on television: flat transfers, matted transfers, letterboxed flat,

16:9, NTSC, PAL - in short,the works. Columbia TriStar has a proprietary film-to tape system that masters

films around the clock, and not to NTSC or PAL, but to an HDTV format, from which the present-day format

masters are produced by down-conversion. Not only will tip-top versions of their films be available for

television, cable, foreign use and the (why so slow?) rollout of DVD, but when HDTV hits, they may be the

studio with the most product to show. Right now the occasional Warner or MGM DVD will equal their quality,

and there are a number of bum discs in the Columbia corral, but by and large, Savant will go for a Columbia disc,

sight unseen and reviews unread, any time.

The New Disc

On to The Professionals itself, which stars Lee Marvin, Burt Lancaster, Robert Ryan,

Woody Strode, Jack Palance, Ralph Bellamy and Claudia Cardinale. Besides its powerhouse cast and breathtaking

Conrad Hall cinematography, The Professionals' strong suit is its snappy and ironic screenplay,

which overflows with great dialog gems. Lee Marvin gets one bonafide classic line which Savant will not

spoil by quoting here.

Writer-director Richard Brooks didn't visit the Western very often but when he did the results were

memorable, as in 1975's

Bite the Bullet, an unusual and special genre entry. Brooks' genre movies

in general date better than some of his more famous titles, many of them overheated big-star dramas. Cat

on a Hot Tin Roof fares better as a Liz Taylor glomfest than theater transferred to film;

The Blackboard Jungle has always played a poor second to

Rebel Without a Cause in the J.D.

sweepstakes. The Professionals hasn't been the subject of cult admiration, and it's not an

automatic classic like

The Magnificent Seven or

High Noon, but restored to its widescreen

glory, it's a highly rewarding and entertaining show.

The Professionals is perhaps the last big American Super-Western before Sergio Leone

hijacked the genre to Italy with the American releases of his Clint Eastwood films (only to be trumped

a bit later by Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, of course). As such it displays the virtues of Hollywood's

late-sixties willingness to depict adult attitudes to sex and violence, as seen in Bonnie & Clyde,

Hell in the Pacific,

Point Blank, Bullitt, et. al.. It's hard to describe to 1999 viewers the charge we got in 1967 from the sheer gutsiness of these movies. The ending of Bonnie & Clyde hit us like a blast furnace. When Steve McQueen broke the language taboo by saying 'bullshit', audiences cheered. The bits of nudity glimpsed in The Professionals and Point Blank showed us that theaters weren't going to burn down if the Hays Code wasn't followed. The charge we felt was a political one, bred and raised as we were on late 50's - early 60's Hollywood pablum where every hero was a gentleman and even the villains

played by predictable rules.

Philip French's Inspiration.

Viewing The Professionals again set Savant thinking about a thesis put forward by

Philip French in his book, Westerns, Aspects of a Movie Genre.

1 French articulated the basic notion that Genre films like Westerns express the political moods of their times more accessibly than than other dramas because genre conventions function as generic allegorical frameworks. The basic Western setup almost always includes stated or implied value judgments of what is right and what is wrong, what makes a hero, and what works and doesn't work in society. Westerns therefore consciously (and sometimes unconsciously) reflect their makers' views on contemporary politics. Even when new, High Noon was much debated as to whether its 'political statement' was conservative or liberal. French points out that John Wayne claimed his decision to make Rio Bravo was in direct response to High Noon. If you remember, at the end of High Noon Cooper shows contempt for his politically craven town by throwing his badge into the dust. According to French, Wayne felt the marshall's abandonment by citizens and institutions represented a criticism of America, and opined that actor Gary Cooper had been tricked into making a left-wing tract. By contrast, Rio Bravo's marshall is a professional supported by other professionals having little contact with or need for help from, the community at large that 'betrayed' Cooper in High Noon.

French took the idea further and categorized Westerns by the American political figures he thought they

most resembled. Thus High Noon and Johnny Guitar are McCarthy Westerns because both show

individuals persecuted or abandoned by hostile political environments. The Magnificent Seven was

judged Kennedy-esque by virtue of its Peace Corps-style American professional supermen taking their superior

skills and firepower out to right wrongs beyond U.S. borders. Goldwater Westerns, on the other hand,

tended to take the patronizing Republican/conservative tack of upholding the past and 'old ways' as the

ideal to be aspired to; there was nothing wrong with men, women or conflicts that good oldfashioned

brawling, spanking, or mayhem couldn't solve. The John Wayne production McClintock! and later

Howard Hawks films like El Dorado fit in here, according to French. French further inflected his

thesis by subcategorizing films having Kennedy content treated in Goldwater style (the LBJ Western),

and Goldwater content with a Kennedy style (the William Buckley Western).

Phillip French's ideas read better now, actually, than they did in 1973; now his grouping of Wayne, James

Stewart and Ronald Reagan into a political force for docile Republican complacency seems incredibly

prescient, considering how history turned out.

The 'Mexican Adventure' Western Subgenre.

Watching this new DVD brought French's book back to mind because it fits nicely with an idea Savant's

kicked around for a long time. The subgenre of Westerns about gun-toting Americans adventuring in Mexico

can be seen as an ever-changing record of U.S. atttitudes toward U.S. military intervention overseas, our

real 'foreign policy', as it were. Nothing defines Americans better than how they comport themselves when

off U.S. soil.

Doublecrossing buddy-buddies.

Vera Cruz.

Let's begin with

Vera Cruz, which is about groups of American mercenaries fresh from our Civil War who hire out to the French occupiers of Mexico. They're torn between helping the revolutionary Juaristas and simply stealing a fortune in gold. Besides being a remarkably modern 'buddy'

picture, Vera Cruz is astonishingly cynical for 1954. Not only do partners Gary Cooper and

Burt Lancaster constantly outdo each other with cold-blooded treachery, Lancaster's psychotic

joy for killing ("Anyone else string with Charlie?") equals the amoral attitude of the mayhem in the

Spaghetti westerns that were still a decade away. Vera Cruz played right in the Eisenhower

years of CIA 'adventurism' in Central America, and one can't help thinking that director Robert

Aldrich was expressing his own radical outrage when he has moral icon Cooper participate in such

unsavory deeds as holding innocent children as hostages.

2 Outgunned by Juarista general Morris Ankrum's troops, Lancaster acknowledges that his gang can't fight its way out, "But they can stop

an awful lot of little kids from growin' up, amigo." Ankrum backs down, and it's clear that

Lancaster's action is no bluff; in one fell swoop Aldrich shows his American 'adventurers' behaving

with a ruthlessness usually reserved for depictions of Nazis. Since the French are presented as

greedy murderous parasites, Roland Kibbee and James R. Webb's script points audience sympathy to the

conventionally virtuous

Juaristas. "Wars are not won by killing children," Ankrum intones nobly, but we are already expected

to know better.3

What tension (and thrills) Vera Cruz delivers center around our delight at seeing how

cynically outrageous things can get. The moral center weakly returns to

Gary Cooper when he eventually sides with the Juaristas against the doublecrossing Lancaster,

but this development smacks of insincerity. Cooper keeps claiming his intentions are just as

mercenary as Lancaster's but it is Burt who does all of the backstabbing, pointedly murdering

several of his own gang including his most loyal follower, a black ex-soldier still in Union

uniform. Cooper's iconic 'goodness' defeats what seems to be Aldrich's aim: To sully

audience expectations of American Heroism and conclude with a cynical apocalypse. The romantic

resolution also seems compromised. Cooper and Juarista lover Sarita Montiel are shown in single

shots acknowledging one another, but in the final wide angle of death and devastation Cooper

walks alone. This echoes the opening caption, " ... And Some Came Alone."

Gunfighters in cool summer fashion poses.

The Magnificent Seven.

1960's The Magnificent Seven plays the fable straight, transposing Akira Kurosawa's

already Western-like fantasy of mercenary might used for noble purposes, into a sagebrush

epic. Seven drips with the Kennedy ideal of putting America's power behind the moral

task of freeing our friends and neighbors overseas from their oppressors. Unlike The Seven

Samurai, which stays inside Japanese society, Sturges' reworking knows that he must

leave the U.S. to find a conflict 'simple' enough to place the dilemmas of his seven gunslingers

in clear relief. Having Yul Brynner and Steve McQueen come to the aid of beseiged American

homesteaders or exploited mineworkers could only dredge up a messy political dimension, exactly

what Americans prefer not to think about, let alone see in their movies. For the

proof of this one need look no further than Heaven's Gate.

If the Mexican revolutionaries are simplified in Vera Cruz, the peasants of The Magnificent Seven

are patronizingly idealized as simple, wisdom-spouting, docile nobodies.

No matter how much Yul Brynner and Charles Bronson say about the virtues of communal farm life,

not for a moment do American audiences identify with Mexican peasants or consider them equal to

the individualized Americans. That's the irony: They may be funny, wise or noble, but the peasants'

most important trait is that they don't count. Eli Wallach's bandit leader's assertion that

they are but sheep to be sheared seems pretty darn accurate, even if the text of the film tries to

characterize it as an evil statement. Mowed down by the dozens in Vera Cruz, here the

peasants die slightly more individualized deaths and are afforded the great honor of hats-off respect

from the Americans. But, even though their widows and orphans grieve over them, their passing means

nothing when compared to the glorious fates of the gunslingers. The little boys listen to Bronson's

sermon about their father's responsibilities, yet it's clearly Bronson they idolize.

The helpless farmers are beset upon by rapacious bandits and the American gunslingers with their

knowhow regarding violence and firepower are naturally drawn to the noble mission of defending

the weak from the strong. This is basically the Kennedy formula, with the bandits being the

simplified Communists who prey like vultures upon the poor. As such they are instant candidates

for extermination, something '50s American movie heroes do best whether the enemy be rampaging Indians

or mutated monsters.4 When at age 13 I watched my older cousin go off to war, Savant

perceived of Vietnam almost completely as The Magnificent Seven come to life. The war

certainly was presented to the public in terms as simple as a Western - there's an evil foe to

be confronted and a helpless population of grateful semi-human peasants to be saved.

The conclusion of The Magnificent Seven seems identical to its Japanese model yet can't

be more different. The surviving Samurai acknowledge the impermanence of their warrior class

in contrast to the farmers, who embrace life and endure. The Samurai may be noble and

magnificent but they also die unmourned, soon to be forgotten. The end of The Magnificent Seven

reverses the Japanese statement about the warrior lifestyle. The gunslingers may die but

they will become legends, what

with the boys bringing flowers to Bronson's grave and the earlier statement that "Anything that

happens around here becomes a song." Brynner and McQueen don't stand staring at graves like the

obsolete Samurai but instead ride into the horizon with epic music blasting out as positively

as it had earlier. These giants are just moving on to more adventures. Keep yer sixguns polished,

kids, there's always another battle to be fought.

PART TWO of this article takes on Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch, and

The Professionals.

Footnotes:

1. French, Philip. Westerns, Aspects of a Movie Genre The Viking Press, NY 1973.

Return

2. Note that the domestic release of 1954's La Salaire de Peur

(The Wages of Fear) was shorn

of all of its political content ... the original full-length version (available on Criterion DVD) explicitly

places responsibility for the misery and poverty of Central America at the foot of a U.S. mining corporation.

U.S. 'adventurism' in real life. Also, the kind of movie Aldrich probably hated was 1939's The Real

Glory, a Marines-in-the-Phillipines adventure that tells the story of U.S. depradations in that country

(read Mark Twain's A Pen Dipped in Acid sometime) by showing Cooper 'suppressing a fanatic

uprising' against benevolent white rule. "Use a .45, nothing else stops those crazy beggars charging

with their machetes!"

Return

3. I find nothing in movies as distilled as this about the truth of war until Kurtz's

Apocalypse Now

speech about little children being mutilated for political terror. And Vera Cruz is considered

light entertainment! The only conclusion is that Americans don't care too much about the fate of little

non-white children.

Return

4. A politically-oriented reviewer of

Them! (1954) decided that the giant ants of that film were

transparent substitutes for insidious, infiltrating Communists, which the U.S. Army gleefully incinerates.

Philip French labeled the Eastern-educated but still treacherous Indian warrior played by Jack Palance

in

Arrowhead (1953). a thinly disguised conflation of Communist provocateur and juvenile delinquent! And you wonder why Rock n 'Roll was considered subversive!

Return

Text © Copyright 1999 Glenn Erickson

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 1997-2002 Glenn Erickson

Go BACK to the Savant Index of Articles.

Return to Top of Page

|

|